When producers go out to their cattle in late winter or early spring and see them itching, or with bald patches, their mind usually thinks lice infestation. Sometimes they run them through and give the cattle insecticide treatment, or have their veterinarian examine them.

But is this treatment helpful or even necessary? It could be just scratching the surface, but Dr. Brenda Ralston and her team have been getting to the root of the problem to see what is actually causing itching in cattle.

Ralston is a Results Driven Agriculture Research (RDAR) research scientist at Lakeland College. Her research centres around products and processes that improve production with food production animals (mostly cattle, but also some sheep), and pharmaceutical research.

Read Also

Managing newly received calves in the feedlot

What should cattle feeders focus on after calves arrive at the feedlot?

Three years ago, the Beef Cattle Research Council (BCRC) called for research proposals relating to itchy cattle and looking at what actually causes itchy cattle.

“It never has been pinpointed what the cause of itchy cattle is,” Ralston said.

Drs. Merle Olson and Denis Nagel with Alberta Veterinary Laboratories (AVL), Chinook Contract Research (Nick Allan, Dr. Joe Ross, Kendall Beaugrand, Ann Hammad and Crystal Schatz), and Lakeland College (Ralston and Andrea Hanson) successfully submitted a collaborative project to investigate what is causing itching in cattle. Their project is funded by BCRC and Alberta Beef Producers.

“We tried to come up with as many factors that could possibly cause itching in cattle,” Ralston said. “We wanted to go out into the field and find herds of itchy cattle to examine and find out what is going on.”

Researchers were able to connect with veterinarians who receive calls when producers think the de-lousing products are not working. These leads gave them seven herds across the three Prairie provinces to investigate

“We were enrolling herds that had more than 30 per cent of their herd that was itching.” Researchers set out to look at 10 itchy cattle and five non-itchy cattle in each herd.

“There were a number of different aspects we wanted to look at,” Ralston said.

At every farm, in addition to the tests that were performed, feed and water samples were taken. The water samples were evaluated for mineral content, as some tie-ups can occur between certain minerals.

External parasites and straw mites

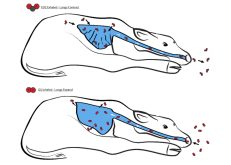

The first aspect they wanted to look at was whether the cattle had external parasites, such as lice (both chewing and sucking) and mites. They came up with a system of where to look on the animals for these external parasites. They then checked the animal over for signs of lice, performed skin scrapings for mites, took photographs, performed counts of external parasites, and scored the animal. In the end, they did not find many signs of lice on the itchy cattle.

They also looked for straw mites in the cattle bedding.

“We wanted to see whether or not it could potentially be causing itching, especially in animals who were bedded on a straw pack,” Ralston said.

They collected samples of the straw used for bedding and used a Tullgren Funnel (an apparatus for collecting small organisms from soil or leaf litter) and checked the bedding to see if mites were present. They didn’t find any straw mites in their samples.

“At least we looked for them and could check that off the list,” she said.

Skin allergy tests

They also tested the cattle for allergies, in much the same way people are tested.

“We wanted to see if some of this itching was the result of some kind of allergic reaction,” Ralston said. There were five animals from each herd (15 total) that were selected for this test. Four exhibited hair loss and itching and one was normal (control).

For this part of the test, she involved a veterinary dermatologist — Dr. Frederic Sauve, with the University of Montreal. “He assisted us because typically there aren’t many dermatologists who deal with food production animals. He helped in selecting what different types of allergens we should be testing the cattle for.”

Researchers tested for a few allergens, including a seven-grass mix, alfalfa, mould mix, weed mix, grain dust mix, histamine (positive control), and saline (negative control). To perform this test, they shaved the animals, drew a pattern on the skin, and injected the allergens.

“Then we waited a period of time and the swelling was measured. We compared the swelling to the positive and negative control. We could tell if there was no swelling or if there was some.”

They also measured heat with an infrared camera. When there is a reaction, there is heat, and a value can be assigned to the reaction. Out of the 15 cattle that were tested, only one animal reacted to alfalfa.

“Dermal sensitivity on the majority of the animals did not appear to be an issue.”

Dry skin

The next test that they performed was to see if the animals simply had dry skin.

“We developed a protocol using a Corneometer, which is the tool used in human cosmetics to measure skin hydration,” Ralston said. “We were using the Corneometer to see whether or not dry skin, just like in people, was causing the itching.”

The itchy, bald patches were looked at in the cattle and compared to a non-itchy area on the same animal to see if the skin moisture was different. Ralston said they tested two distinct areas on the same animal because, they assumed, just like humans, no two animals have the same level of skin moisture. This was a bit of an unorthodox approach, and there is little to no research on cattle skin moisture, but they wanted to cover as much as they could while they had the producers’ cattle to work with.

“If there was something to dry skin causing itchiness, we wanted to pick that up.”

They compared skin moisture not only within a single animal but also between all itchy animals and all non-itchy animals. The issue became, which came first — the dry skin and then this itchiness or did they scratch the hair off and the skin became dry because of the lack of hair? That became a bit of a conundrum to figure out.

Ultimately, there wasn’t a significant difference in most herds. It was difficult to compare different herds, because different rations could affect the level of oils in the skin, such as if a producer fed canola meal. Instead, researchers compared itchy and non-itchy cattle within a herd.

“When I ran the stats on this study, there was only one herd that showed a significant difference between the itchy and non-itchy cattle in terms of skin hydration which was interesting,” she said.

While there are ways of increasing skin moisture in animals, it doesn’t appear to be a big factor in the study.

Nutritional deficiencies

Researchers also wanted to investigate nutritional deficiencies and see if they could cause itchiness in cattle. Initially, they pulled blood samples from the cattle and compared the itchy to the non-itchy cattle within the herd.

“We checked them for things like vitamin A, vitamin E, copper, manganese, cobalt, iron, magnesium, molybdenum, selenium and zinc. We ran all of these to have a look,” Ralston said.

The blood samples were also tested for mycotoxins, as certain ones in feeds can cause itchiness.

“We wanted to see if some of those might be in play with the itchy cattle,” she said. There wasn’t anything that showed up for mycotoxins, she said.

Once she got into the study, and had the go-ahead from a few producers, it was decided to have a skilled veterinarian — Dr. Denis Nagel — perform liver biopsies on some of the cattle. Liver biopsies more accurately assess the nutritional status of individual animals because most of the vitamins and minerals are stored in the liver. The same vitamin and mineral panels were run on the liver biopsies as the blood samples.

The results

The results came rolling in for Ralston and the team. Out of 101 cattle that were looked at, there were 21 that had lice, and 18 had less than 10 lice per square centimetre.

“The lice infestations were really quite light, and on only 20 per cent of the cattle. There was no correlation between itching and having lice either, and it didn’t seem linked to the hair loss.”

In the dermal hypersensitivity, there was no significant difference between itchy and non-itchy cattle.

The skin hydration tests showed that one herd had significant differences between the itchy and non-itchy cattle. “But over the seven herds, there wasn’t a significant difference,” Ralston said.

The blood serum results did not show any differences between the itchy and non-itchy cattle. However, in the animals that had liver biopsies, when they were tested for copper deficiency, a significantly lower level of copper was observed for the itchy cattle compared to the non-itchy cattle.

“We didn’t have a lot of liver biopsies (to work with), so the results are interesting. We think perhaps copper deficiency may be a contributing factor to itchy cattle,” Ralston said.

The team has since put in another application to a grant agency to do more research on supplemental vitamin and mineral products — including copper — and giving them to itchy cattle to see if it resolves the issue.

Ralston and the team are grateful to the veterinarians and the producers who helped them identify itchy cattle herds to study and allowed them to collect samples from their animals.

“Without their co-operation and the use of their animals, there would be no study. Alberta Beef Producers and BCRC were also an integral part of the study, through their funding and interest in the cause of itchy cattle, to help the livestock industry.”

Jill Burkhardt, her husband Kelly and their three children own and operate a mixed farm near Gwynne, Alta. Originally hailing from Montana, Burkhardt has a range management degree from Montana State University