It would be wonderful if reason and common sense would govern everything we try to accomplish. Unfortunately, one of the greatest myths of common sense is that everything that seems obvious at first is. Things only become obvious after you know all the answers, and they never all come. A complicating reality is that humans often fail to learn from history and are bound to repeat it. Some get hung up in misguided delusion from the start, then when given the chance, promote unreasonable solutions. War stands as the supreme example.

A less dramatic example surfaced in an op-ed that ran in the Los Angeles Times and Palm Springs Desert Sun in January. The opinion piece was written by Jeff Sebo, a clinical associate professor of environmental studies, affiliate professor of bioethics, medical ethics, philosophy and law, and director of the animal studies master of arts program at New York University. I give Sebo’s credentials, as printed, wondering who this gentleman is. I also wonder how many California residents understand the significance and background to Sebo’s diatribe other than that the price of a dozen eggs peaked at US$7 (up US$5 through last year) at the time of writing in January, with many retailers facing empty shelves in their egg section.

Sebo’s claims include:

- The high prices might be temporary, but problems causing them won’t go away as long as large-scale animal farming continues.

- The reality is large-scale animal farming is unsustainable.

- Ninety-eight per cent of animals are raised on factory farms, which are very bad for animals.

- Animal farming is incredibly inefficient consuming about 83 per cent of farmland and 56 per cent of fresh water, while producing only 18 per cent of our calories and being responsible for an estimated 14.5 per cent of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

- Animal farming is an incredibly inefficient method of food production and a major contributor to climate change.

He briefly mentioned avian influenza as one cause of depressed egg production. This year’s strain of highly pathogenic avian influenza turned out to be one of the deadliest strains ever to affect the industry. National bird loss exceeded 50 million.

Read Also

Effect of wildfire smoke on respiratory health in beef cattle

Of all domesticated species, cattle have the smallest relative lung capacity, making them particularly vulnerable to wildfire smoke.

Proposition 12, fully implemented on Jan. 1, 2022, banned layers in cages, and the import of eggs from states not following suit. Sebo concludes, “The California egg shortage is a reminder that as long as animal farming remains at the center of our food system, the system will remain at the center of our global welfare, health and climate problems.” It’s too bad people of this ilk even get space in papers.

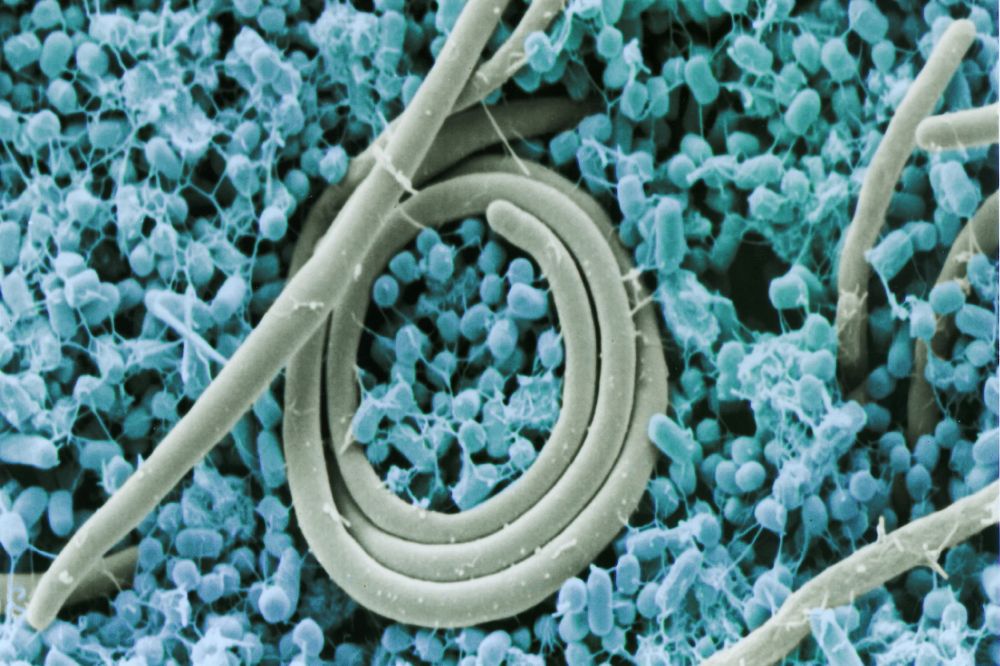

Animal agriculture continues to get a bad rap over its role in antimicrobial resistance. I do not deny antimicrobial resistance is a critically important issue and that the agriculture industry should continue to decrease its demand for antimicrobials and always use them judiciously. While much has been accomplished in the North American animal agriculture scene, we must continue to help tackle problems in human medicine as part of the One Health discussion.

COVID affected the medical community in many ways. For one, response to the pandemic reversed progress made in the fight against antimicrobial resistance in the U.S. (as reported by the Centers for Disease Control). The pandemic pushed back years of progress made combatting antimicrobial resistance. Resistant hospital-onset infections and deaths increased by 15 per cent during the first year of the pandemic and more than 29,400 patients died from antimicrobial resistance pathogens.

Dealing with an all-new pandemic of zoonotic origin creates a sense of defenselessness. The temptation to repurpose antimicrobials in our arsenal, and resort to innovation, is understandable. The consequence of doing so has long-term implications.

The pandemic produced diminished effectiveness of medication used to treat illness, something we failed to recognize as a consequence in the beginning. In North America, progress has been made ascertaining farmers’ and veterinarians’ behaviours and needs surrounding antimicrobial resistance. When we look at the global consumption of various antibiotics, we see approximately half of all antibiotics used in animal husbandry are consumed in China, followed by India. This takes antimicrobial resistance onto a global stage.

Currently, antibiotic resistance is linked to:

- Over-prescription of antibiotics.

- Patients not finishing the entire anti-biotic course.

- Overuse of antibiotics in livestock and fish farming.

- Poor infection control in health care settings.

- Poor hygiene and sanitation.

- Absence of new antibiotics being discovered.

Priorities changed. Human health care assumed a greater role in the battle against antimicrobial resistance.

Producers who take underfed cows onto the calving grounds face issues of poor-quality colostrum for newborn calves. The risk is immune incompetence and the threat of scours and respiratory infections. The unintended consequences associated with lactating females in poor condition are delays in the return to heat and poorer conception rates when cows and calves enter the breeding pasture. Over time, poor conception rates spread the calving interval and lengthen the calving season.

Advice from an old rancher: As you think about animal health management in your operation in the coming year, focus on why you have fires and not how you put them out.