One of the highest input costs when raising cattle is winter feeding. Some ranchers are shaving winter feed costs and labour by wintering their summer-born calves with the cows and not weaning the calves until spring.

Dr. Joseph Stookey, a professor of animal behaviour at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine in Saskatoon, has a cow herd of his own and for many years has been leaving the calves on the cows until spring. “Dairy cattle perform best in their next lactation if they are dry for about 45 to 60 days prior to calving again. If dairy cows only need to be dry for that short length of time, why not beef cows? I normally wean my calves less than 60 days before the cows’ first possible calving date, if the cows are in good condition,” he says.

Read Also

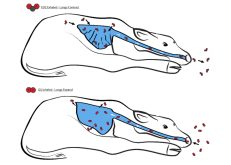

Reducing disease risk from calving season onwards

With winter calving almost at a close, grassland producers are preparing for their own spring calving season. Chad Ross calves…

“My cattle are usually overconditioned — sometimes embarrassingly fat! If I were to wean their calves at a more conventional age of 6.5 to seven months of age, it would simply give the cows more time to get fatter. However, if my cows were to become too ‘pulled down’ in weight from lactation I would probably wean their calves sooner.” Leaving calves with cows through winter works best with moderate-milking cows, and not so well with heavy-milking cows that take more nutrition for lactation.

“The evolutionary function of milk produced by mammals is to supplement their young until the young can consume ‘adult food.’ Why wean calves prior to them being able to live completely off forages? I don’t see the purpose of weaning them early, if it means I have to supplement their diet with more energy and protein to keep them growing. That’s what the milk does for them,” says Stookey.

“It is easier to supplement calves through winter using their mother’s milk, than to supplement them with grain. As the calf ages, it becomes more adapted to consuming adult food. The natural lactation curve matches the needs of the growing calf; the closer the calf gets to adulthood (and the closer the cow gets to the next calf being born) the less milk is produced. Obviously you need to feed forages that have adequate nutritional value for the cow to maintain good body condition during lactation. Some poor-quality forages make it impossible for heavy-milking cows to maintain body condition,” he says.

Before domestication or selective breeding, cows gave a moderate amount of milk and fed their calves through winter without problems. “By selecting for heavier weaning weights in beef cattle we have indirectly selected for heavier milking cows. Such cows become too thin on range pasture if lactation continues very long into winter. I want cows that ‘save’ some nutrients for themselves without getting too thin during lactation, so I am not pushing for heavier weaning weights and heavier milking cows. With my cows, weaning time can be delayed until spring, but that’s not true for all beef cows.

“I like being able to manage the herd together through winter. It makes life simpler for me, with one group to feed. Some producers think they have to wean their calves before winter or udders will freeze and be damaged, but there are plenty of fall-calving herds to disprove this idea,” says Stookey.

His cows calve in April and May. “Perhaps that helps me justify leaving calves on the cows well into winter, but I think I would aim for just a 60-day dry-off regardless of calving season. It’s not the calving date that made me consider leaving calves on the cows that long,” he says.

Some of his calves are weaned naturally, before he uses a two-stage weaning program with nose flaps, which he begins about 60 days before calving. “The naturally weaned calves have the least amount of stress possible for weaning,” says Stookey.

Many people seem to think that declining quality of pastures in late fall means they need to supplement the cow to support lactation if she is still nursing a calf. “But in reality, as the quality of forage declines, the milk curve is winding down at the same time the calf is gaining ability to handle forage with a fully functioning rumen. You don’t have to supplement cows near the end of lactation,” he explains.

More from the Canadian Cattlemen website: The Top 10 tips to an easier calving season

“Nutritionists say it is inefficient to feed a cow so she can convert the nutrients to milk, when you could feed the calf directly. If you feed a cow grain so she can milk better, then yes, it’s more efficient to just feed the calf grain. But I don’t feed grain to my cows or my calves. I expect both of them to utilize the forage in front of them (grass or hay). If you keep good grass or decent hay in front of them, they will stay in good condition,” he says.

“I am convinced that it’s easier to keep them in good condition (and takes less energy) than to let them sink to a poor body condition and then try to build them back up. Feeding calves grain — any time in their young lives — retards their ability to become a full-fledged ruminant, able to fully utilize and thrive on forages.”

The important thing is to make sure cows are adequately fed (enough quantity and quality of forage) if a person leaves the calves on them through winter. “The majority of cattle cases of neglect and abuse investigated in Canada by the SPCA include cow herds that have not yet weaned their calves. And contrary to what many producers believe, creep feeding calves does not ‘reduce the pressure’ on the cows. A calf will drink and take all the milk a cow will produce, regardless of whether he’s on creep feed or not.” Leaving calves on the cows through winter will only work if the cows have adequate feed and are not genetically programmed for heavy milk production.

LATE WEANING IN NORTH DAKOTA

Ken Miller has been bale grazing cow-calf pairs through winter for the past five years on his ranch in central North Dakota (25 miles south of Bismarck). “The fields I’m doing it on were originally poor cropland with a lot of bare ground,” he says. He is improving the soil with the aftermath of bale grazing plus the nutrients from the cattle manure and urine.

“I feed some high-quality hay along with some rank, coarse hay,” he says. The cattle eat some of the poorer-quality hay to add fibre to their diet to balance the good hay. They trample and bed on the rest, putting more organic matter and carbon on the ground.

“We are more than doubling pasture production, and we’ve cut our winter feeding costs. I burn less than 100 gallons of diesel fuel in my tractor, to feed 100 pairs. Some people think that when it is cold the calves won’t perform very well, wintered with their mothers on hay, but they do quite well — and our winters can be very harsh. We wean in late March. Since we don’t calve until late May/early June the cows have adequate time to recover,” he says.

When the calves are weaned, he feeds them separate from the cows for about a month, still bale grazing. He trails the cows home, leaving several older cows with the calves. He then puts the calves back with the cows again so everything can be run as one herd, saving time and labour.

“There is no stress weaning at that age. The calves are about 10 months old and don’t miss their mothers at all,” he says. Some have already been weaned by the cows.

“I run them as yearlings, to sell in August or September. We are currently working into smaller-framed animals that are more efficient and keep some until two-year-olds, to finish on grass,” says Miller.

Wintering calves with their mothers, there is no sickness, compared to weaning in the fall. “We used to give pre-weaning shots, but we don’t need to do that anymore. We use a mineral program in the winter, but that’s the only supplementing,” he says.

The cattle graze as long as possible and when grass gets covered with snow they start bale grazing. “We usually graze into the first part of January. We used to feed five to 5-1/2 months, and now we’re down to about four months of feeding, even in bad winters.”

Miller says you can’t do this if you calve early, like February. “Calving in May our cows don’t have to be in top shape through winter. Even if they’ve lost some body condition by the time you wean the calves, the cows fatten up by calving time.”

Weaning the calves at a younger age generally results in more sickness. “I prefer to leave them on the cows. That way the calves learn from their mothers how to graze through the snow. Calving in May/June limits a person to selling light calves if you market them in November. But if you leave them on the cows and run them on grass the next year to sell in August or September they are a good weight and you don’t have much feed investment in them,” he says.

“We used to calve February/March, wean in late October and background them, to sell in January/February at 800 pounds. But we had a lot of feed and fuel invested in them,” Miller says.

“It’s amazing how easy our calving is, out on pasture, and we have less sickness in baby calves. With the bad weather we had last spring, ranchers who calved in March and April were worn out checking cows and dealing with sickness.” He prefers to calve when it’s warmer, and let the cows take care of the calves through their first winter.

The replacement heifers wintered this way with their mothers make better cows; they are more ambitious to travel around finding something to eat rather than waiting for a feed truck every day in the winter.