Foot rot is an infectious disease that causes swelling, pain, heat and inflammation in the foot, resulting in severe lameness that appears suddenly. The opportunistic pathogens require a break in the skin, however, to enter the foot. The main bacterium we deal with is Fusobacterium necrophorum.

Importance of diagnosis

Lameness may be from a nail in the foot, injury (a pulled tendon or broken bone), an abscess or snakebite. Dr. Eugene Janzen from the faculty of veterinary medicine at the University of Calgary says a common cause of lameness in range cattle is a problem in the hoof such as a hoof crack, an overgrown toe that’s broken off, or even a hoof abscess.

Read Also

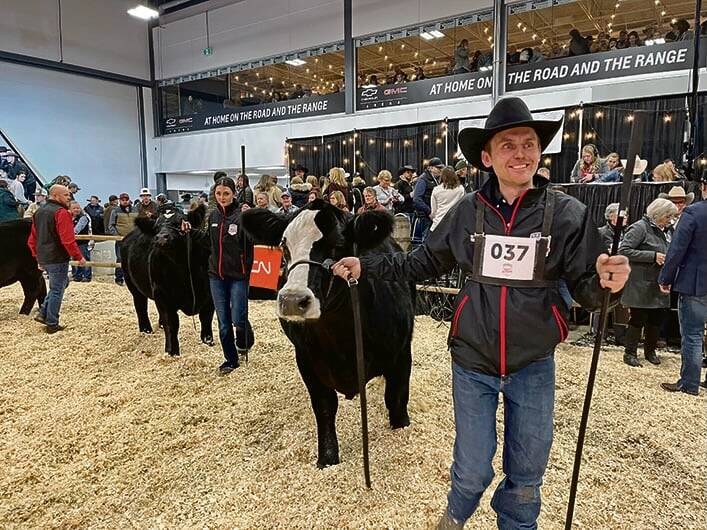

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

Even though an abscess is an infection, it won’t respond to systemic antibiotics. Abscesses must be opened and drained, to relieve pressure and pain. “Swelling in other areas of the body are not as painful because skin will stretch, but with an abscess in the foot there is bone on one side and hoof horn on the other side, so the pressure is excruciating,” says Clark. “It’s like the pain when we smash a finger or toe and swelling underneath the nail makes it worse. If you’ve ever had an abscess under a fingernail or toenail, you can understand how painful it is for the poor cow. You have to relieve the pressure,” he says.

An abscess is a localized infection, sealed away from blood circulation, and can’t be adequately treated with antibiotic injections. Flushing it out and treating topically is the way to deal with it.

“Foot rot is a different kind of infection. The cow may have stepped on a stone or something sharp that cuts through the skin between her toes. Once the skin is pierced, bacteria in the environment can easily enter, and get into the fat pad between the toes. Fusobacterium necrophorum is everywhere — one of the common bacteria that assist with decay and rotting of dead things,” Clark explains.

“The tissues between the toes actually start to rot. The toes are separated because of the infection and swelling. There will also be symmetrical swelling of tissues above the hoof. It will be hot to the touch and the skin (on a white-legged animal) will be red. The lesion smells like rotting flesh. If you look closely you can see gray-green rotting tissue protruding,” he says.

“It’s easy to look at a lame foot and see whether it’s foot rot. Even from horseback you can get close enough to see the swelling between the toes. If it’s foot rot you can treat with antibiotics and it should get better. If there’s no swelling, it’s not foot rot and treating it will not help. In that situation, you need a closer look at the foot and remove the stone or the nail or deal with the abscess or whatever the pain-causing situation might be,” says Clark.

“The swelling from foot rot is below the fetlock, and just above the hoof,” says Janzen. If the swelling extends above the fetlock joint it’s probably not foot rot.

“Infection in the interdigital cleft may be due to a variety of bacteria ubiquitous in the environment. The common one is Fusobacterium and this is the one for which a vaccine has been created. Other pathogens can be involved as well, and complicate the infection. None of them, however, can produce foot rot on their own without a break in the skin. The people who have tried to reproduce foot rot in experimental trials have all had to scarify the interdigital area,” he says.

“Thus you need two things for foot rot to occur — the ugly bacteria and the injury. In dairy cattle we often see foot rot in what dairy practitioners call ‘new barn syndrome’ which means the cows have more interdigital injuries if the concrete hasn’t been worn off and smoothed yet. If cows are walking on an abrasive surface and also have to walk through a slurry of manure, this becomes a perfect combination for foot rot,” Janzen says.

“The literature about foot rot states that incidence in range cattle is something between one and four per cent but livestock people here in Alberta would probably say it’s higher, depending on the year. Also, if a ranch has cowboys training horses, the owner tells me their foot rot rate is high. The cowboys want roping practice so they catch and treat any cattle that they think might have foot rot — and they may be over-treating.”

On the flip side, some ranchers don’t ride among their cattle often enough to see the ones with foot rot and may not treat them soon enough. Long-standing cases may result in serious complications like joint and tendon sheath infections.

Treatment

“Penicillin will work, but you need to dose it daily. Many other drugs have a foot rot claim on the label, but there’s little point in using something like Nuflor or Micotil because they are more expensive. I use long-acting oxytetracycline, since it is less expensive, and generally one treatment will do it. The only drawback with this drug is that there is a fairly long withdrawal period, so you need to be very certain you are treating foot rot,” he says. You wouldn’t want to discover later that the animal has a broken foot (rather than foot rot) and the best choice would be slaughter.

“If the cow is at home in the yard where you can treat daily, you can use the oxytet that’s not long-lasting, or use trimethoprim sulfate,” says Janzen. “If you are not absolutely sure it’s foot rot, and it might be something else like a broken bone in the foot, and one of your alternatives might have to be slaughter, consider using Ceftiofur since it doesn’t have a withdrawal time, in Canada,” he says.

“For treating range cattle, sustained-action antimicrobials provide coverage for more than one day. It doesn’t matter which one you use but long-acting oxytetracycline is probably the most commonly used. It’s probably best to save the more modern drugs for when oxytet no longer works. Some of our pharmaceutical people have cautioned us about using the sustained-action antimicrobials that are more organ-specific, such as the drugs that concentrate in mammary tissue or the lungs, for instance (for treating things like mastitis or pneumonia). Those would not be our first choice for treating foot rot,” Janzen says.

“If the lameness doesn’t get better after antibiotic treatment, there are only two explanations,” says Clark. “One is that it is not foot rot. It’s an abscess or some other problem. Second, if you let foot rot go too long before treating it, infection can spread from the fat pad between the toes and get into the joints. This is much more serious. Once the infection gets into the joints it starts destroying the cartilage. Even if you can eventually clean up the infection (which is much more difficult once it’s in a joint), you are still dealing with an arthritic joint. That animal will still be lame, and you are faced with either slaughter or possibly amputating the toe — depending on the circumstances. Those are your only choices,” he says.

Janzen says that half the cows sold as culls because of lameness are suffering from complicated cases of foot rot. “It’s very serious if the infection has got into the joint, and even worse if it’s into the tendon sheath because antimicrobials won’t get in there,” says Janzen. There’s no economical way to treat that condition in cattle.

This is why it’s important to catch it early. On a longstanding case of foot rot — in situations where cattle are on large range pastures and you don’t see them every day — it might take two doses of antibiotic to clear up, according to Clark. “But the main thing to keep in mind is that if it’s not starting to improve after the first treatment, you need a closer look at the foot to make sure of what you are dealing with,” he says.

In most cases a producer can make a diagnosis of foot rot, and treat appropriately. “But rather than assuming a lameness is foot rot, figure out why the animal is lame. There are many reasons that an animal could go lame. This is why I am nervous about using dart guns in which an antibiotic can be delivered at long distance. Advertisements for these guns often use foot rot as their example, but if you can’t get close enough to get a good look at the foot, that’s not a good idea!” says Clark.

“In the old days, before we had all these new drugs, we treated foot rot locally with an antiseptic or antimicrobial wrap around the foot,” says Janzen. “I’ve also read about research where people cleaned the interdigital cleft with soap and water. If you did that religiously for four or five days in a row, the foot would heal just as well as it would with antimicrobial treatment. But no one wants to lift up a cow’s leg five days in a row to wash out the foot! Maybe 20 years from now if society says we can’t use antibiotics anymore, we may have to resort to these sorts of treatments again!”

Prevention

Janzen says some ranchers are fencing off water holes and lifting the water with solar pumps to a trough on higher, dry ground. “Then cattle don’t have to go into the water holes to drink. The PFRA in Saskatchewan was instrumental in demonstrating to producers that cattle preferred to drink from the troughs rather than have to wade in the filth and mud.”

There is a foot rot vaccine available. “It’s been in use a long time, but there isn’t a clinical trial that actually demonstrates whether it works or not,” says Clark. “The problem with this vaccine is that in many producers’ minds it is a lameness vaccine. But it is only a foot rot vaccine, and foot rot is not as common as they think, so it’s hard to gauge whether the vaccine has any benefit. In the absence of evidence, I am a little cautious,” says Clark.

Janzen adds, “If foot rot is caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum (the) vaccine will probably be protective, unless the infection is complicated by or caused by Bacterioides spp. In Canada, some producers give their bulls this vaccine when they do their breeding soundness evaluation in the spring,” he says.

“When I was growing up, everyone believed that foot rot could be prevented by feeding organic iodine with the salt. Many ranchers still feed iodized salt, or salt blocks containing iodine, in an effort to prevent foot rot. Whether it prevents foot rot or not, is equivocal. The level at which you’d have to add iodine, or organic iodide, in salt would likely be prohibited by the federal government regulations in Canada. Organic iodine has been withdrawn in Canada for that application,” says Janzen. “You can still put iodine in salt, but at such a low level that it’s hard to tell if it helps.”