Reg Steward knows his way around a cattle herd.

Steward works with AgSafe BC as a ranch safety specialist, regional safety consultant and field operations advisor. He also puts on clinics and ranch days throughout the country.

When moving cattle, the safety of handlers, their team and their animals all boils down to three things, he says: the cattle themselves, the handling system and the behaviour of the team.

Read Also

Mycoplasma bovis in beef cattle causes more than pneumonia

M. bovis causes pneumonia and is a major cause of infectious arthritis in calves and feeder cattle

Whether a rancher is moving cattle 20 kilometres down the road or 20 feet from one pen to another, correctly managing all three mitigates risk to people and their animals.

Managing the cattle

There are a lot of similarities between cows and humans, says Steward. Just like how humans interact with their world, cattle behaviour is also based on genetics and life experience, he says. Every interaction between an animal and a human trains that animal on how to react in the future. If a handling session becomes stressful, that animal is going to be “trained to associate handling with high stress,” says Steward.

Steward focuses on low-stress cattle handling, with adequate pressure. It’s an approach he’s heard about from other cattle handlers, such as Dylan Biggs out of Alberta and Curt Pate in the United States.

This approach recognizes that cattle are prey animals, constantly scanning their surroundings. Body language, such as tail flicking, erratic movements, raised ears and snorting, indicate agitation. Even a small thing like sideways movement is a sign that the animal is trying to make itself look bigger, says Steward. As a handler applies pressure on the animal to move, these are signs to watch for.

When an animal starts reacting to someone entering its space, the handler knows they’ve entered the flight zone. A handler must consider how they enter the flight zone and be aware of when they’ve reached the zone. For example, the animal may stop eating, look at the handler or point its ears.

“Entry into the zone will create a response. It will usually cause the animal to move away from you, in the opposite direction of your approach. The speed with which you enter the flight zone will often dictate the speed that cattle begin to move.”

Not every animal is going to have that same zone and it may not be a perfect circle around them; it may be pear- or D-shaped, says Steward. An animal that has been handled by a 4-H kid could have a flight zone of zero, while an animal that has only ever been in a pasture might have a flight zone of a quarter mile. Successful handlers recognize the edges of their animals’ zones.

“You can have 200 cows in front of you and 20 of them will always be breaking off and the other 180 will just go straight down the road,” he says.

Given that not all the animals will respond the same way to pressure, livestock handling is more of an art than a science, he adds.

“Understanding this can help us be a student of the game and create a desire for us to be successful cattle handlers.”

Members of their team, be they animals or machines, will make a difference in the flight zone as well, says Steward. ATVs can be a loud but effective tool for moving cattle, but how do animals behave around them? The same can be said for dogs and horses, or whether the rancher travels on foot among the cattle. It all depends on what the cattle are used to and the experiences they have had.

Steward knows, based on his animals’ behaviour, what has happened in his pasture before he arrived. For example, his Hangin’ Tree cow dog looks more like a coyote or a wolf than the border collies he used to have, he says. If his cattle have had any recent run-ins with predators, they react to his dog differently than if they haven’t. If they don’t react to the dog, that’s good, he says, since he knows the cattle haven’t had any recent events. Handlers must adjust their management strategies based on how the animals are feeling.

“Understanding the impact of predation, understanding the impact of the weather and modifying your management of those as much as humanly possible makes for a more manageable herd. Most livestock handlers know the impact that such things have on the livestock and your job is to facilitate the easiest way around or through that particular stressor.”

The human side

While he specializes in working with cattle, Steward has seen firsthand how working with people is just as important when mitigating risk. The industry has improved on techniques and tools to create low-stress cattle handling situations, he says, noting the work by Temple Grandin over the last few decades. But our people handling skills need some work.

Animals will pick up on the vibe of the team, he says, so making sure a handler and the team are in the right mental space, whether that’s a group of family members or hired staff, is going to have a huge effect on the success and safety of a handling session.

“You’ve got the mood and the energy, positive or negative, that you bring to this. These cows will respond to that,” he says. “They’ll respond to the movement of the handler, to the posture, to the volume and the tone of their voice. It’s important to be aware of what we’re thinking, feeling and doing when we’re working with the cattle and when we work with the people.”

Proper communication is the next step in the cattle handling evolution within the industry, says Steward, but that is going to take some work. If two handlers come into a session, both thinking they are creating a low-stress environment without actually talking to one another, Steward says they are both going to come out of that situation with more stress while thinking the other is an idiot. That situation isn’t going to create success.

“We, as livestock handlers, have to communicate and be on the same page. We may both be ‘doing low-stress cattle handling,’ but if we have two different interpretations of what that looks like, that creates nothing but tension and that reflects itself in the cattle. But it also is a very negative interface with your workers and your family members,” says Steward.

Weather can affect the vibe as well, he says. Animals will move more slowly and humans will be stressed out in the heat, while cold and damp situations won’t help the team’s demeanour, either. Handlers need to make sure everyone stays hydrated in the summer and warm and dry in the winter to manage the stress the weather brings.

Rushing through any job creates more stress than necessary and when it comes to working with cattle, Steward says to take it slow and plan for sessions to go longer if needed. If a handler thinks they are going to need four hours for the job, they should be setting aside eight to ensure they have time for either an unexpected delay or a slower session than anticipated.

The handler can minimize loud noises such as banging and shouting, which is important since cattle have such sensitive hearing. Having a strong team with efficient communication can eliminate angry outbursts that will only make the situation worse, both for the animals and the team members.

An effective handling system

When moving animals through pens and livestock handling facilities, having an effective system is the third important part of low-stress handling, says Steward. The more easily an animal can move through the system, the less risky it is to both the handlers and the animals.

Through the Canadian Agricultural Safety Association and Keystone Agricultural Producers of Manitoba, Steward helped update the Safe and Low Stress Cattle Handling Manual in 2021.

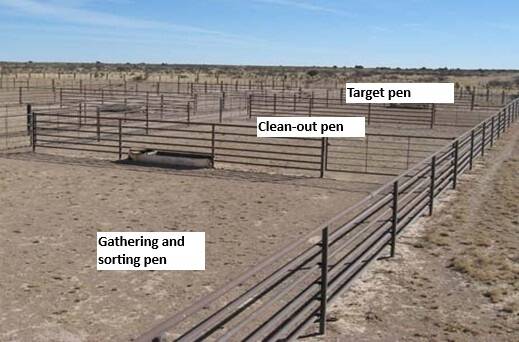

One thing Steward noticed was a need to move away from conventional cattle handling, where handlers moved cattle from pen A to pen B. This can be very stressful, especially if animals are going into the wrong areas. Steward suggests a third pen, which he calls a “clean-out box,” where animals can be further sorted without risk of escaping back upstream or becoming a risk to handlers when they start to forcibly move the animal where it doesn’t want to go. The clean-out box becomes a third option to be cleaned out as often as needed, says Steward.

It also minimizes yelling, and prevents situations such as people jumping in front of cattle or slamming gates and the tension after the “goalkeeper” fails to stop a wayward animal.

“Your employees and mostly your wife will love it.”

As herd animals, cattle feel safest with other cattle and can become agitated when isolated.

Keeping cattle in groups until necessary can improve their behaviour and make them easier to work with, says Steward.

While handlers may already focus on the behaviour of the cattle, managing the team and the handling system can improve the situation, creating a safe space for the handler and their team. c