Anaplasmosis, caused by the rickettsial hemoparasite Anaplasma marginale, is the most common tick-transmitted disease of cattle worldwide. Domestic and wild ruminants, including cattle, sheep, goats and deer can be infected. Only cattle develop clinical signs. Anaplasmosis is endemic in the U.S. where it represents a major obstacle to profitable beef production.

Two tick species common in Western Canada, Dermacentor variabilis (American dog tick) and D. andersoni (Rocky Mountain wood tick) are equally competent in transmitting A. marginale. It can also be transmitted mechanically by biting flies, needles and equipment contaminated with microscopic amounts of infected blood. The smaller male tick is known to move between cattle and deer while feeding so deer become vehicles for infected ticks.

Read Also

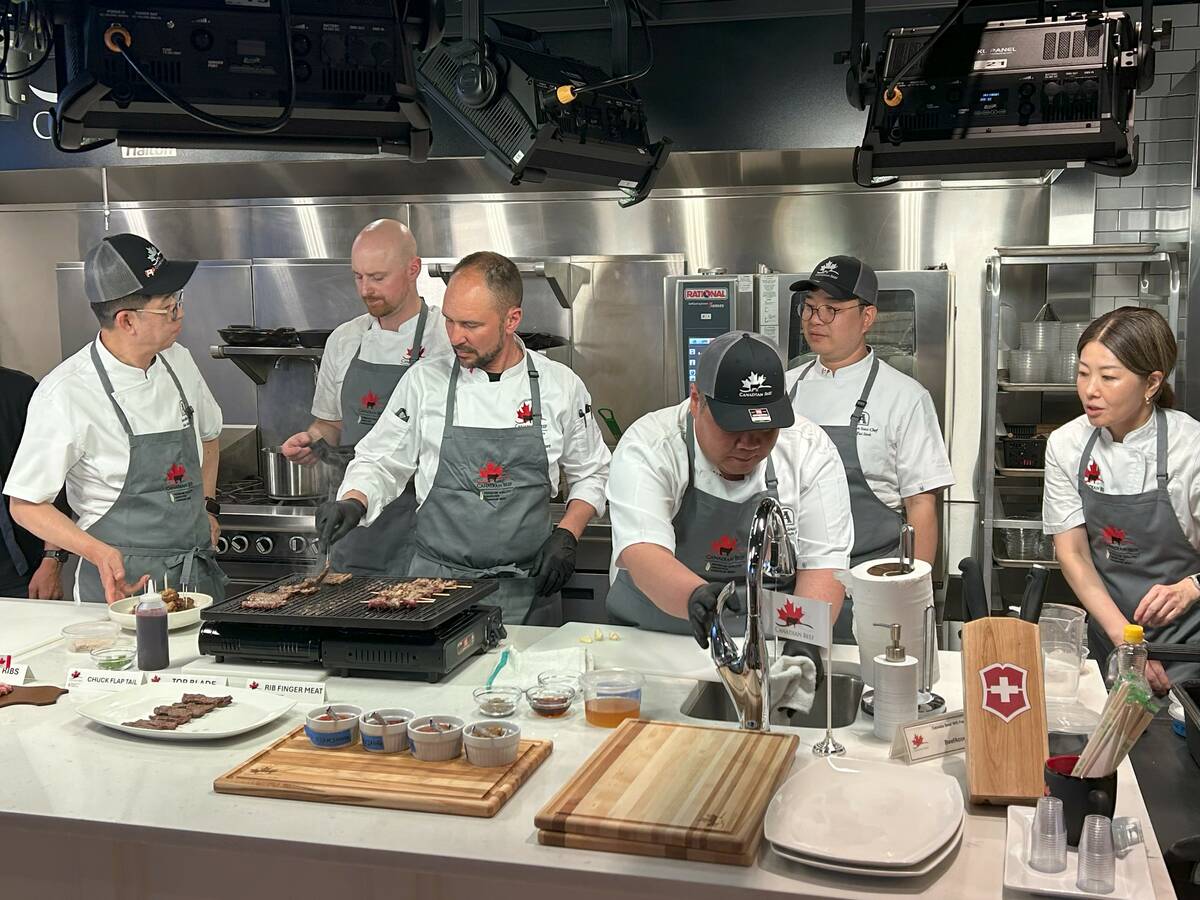

Promoting Canadian beef in Korea

Canada Beef reports on recent activities, including working with an influencer and an executive chef from Korea

Cattle of all ages can become infected, but the severity of disease is age dependent. Illness is rare in animals under six months of age and increases in severity as animals mature to a point where 50 per cent of those older than two years with clinical anaplasmosis may die if untreated. Milk production in affected dairy animals is severely reduced.

Signs of anaplasmosis are associated with destruction of red blood cells and include anemia, icterus, fever, weakness, abortion and death. Introduction of anaplasmosis into a naive herd can decrease calf crops by 3.6 per cent and increase cull rates by 30 per cent. Studies show 16 per cent of pregnant carrier cows transmit A. marginale in utero producing persistently infected offspring.

Recovered animals remain lifelong A. marginale carriers, including those treated with injectable tetracyclines. Anaplasmosis remains a serious and endemic production disease in the U.S. and a substantial impediment to unrestricted trade in North America. Successful measures to control and eradicate anaplasmosis are confounded by the lack of approved antimicrobial regimes that eliminate infections, less-than-perfect diagnostic tools and the lack of effective vaccines.

The major risk of introducing anaplasmosis to Canada is through importation of infected livestock. In two of the five Canadian outbreaks it appeared to have walked across the border. It is not known why the disease has not become established in areas of Canada adjacent to the United States where it exists. In 2007, many Canadian stakeholders clearly supported retention of the current federal anaplasmosis domestic disease control program out of fear it could become established.

Effective anaplasmosis control needs to be directed from the perspective of several important realities:

1. The endemic nature of anaplasmosis and the tendency for it to become established in large populations of cattle if an industry lets its guard down on controls.

2. Tests for anaplasmosis are not perfect, but are getting better and can be used effectively to design control programs. The competitive ELISA test (cELISA) used today is much more sensitive in detecting early infections and becomes highly sensitive beyond 42 days post-exposure, especially when paired with a newer PCR test, which detects DNA fragments of A. marginale. Direct examination of blood smears remains a gold standard. The accuracy of anaplasmosis testing has moved into the comfort range for effective control programs.

3. An oral dose of g chlortetracycline (CTC) at 4.4 mg/ kg/day (U.S. approval) over 50 days is an economical and highly effective method of clearing A. marginale from infected animals and eliminating carriers. On the other hand, injectable oxytetracycline (five daily doses or long acting administered twice) can be used to effectively treat sick animals, but carrier animals persist. Controlled clinical trials have shown extended exposure to CTC is the key, not high doses of antimicrobials. Chemosterilization in the face of active infections does have limitations. First, anaplasmosis could potentially be a serious problem in dairies where any uses of products with withdrawal restrictions create serious financial issues. A second limitation of this approach is based on the fact in Canada there are presently no antimicrobial compounds approved for elimination of persistent A. marginale infections in cattle. There of course are always ethical questions around long-term antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance.

Anaplasmosis is not a regulated disease in the U.S. The first edition of a “restricted feeder program” for Canada was introduced in 1997. For the first time U.S. feeder cattle could be imported into Canada without anaplasmosis tests under stringent post-entry conditions, which included treatment with tetracyclines. Under these provisions, cattle moved directly into licensed feedlots to be finished for slaughter only.

The intent of the restricted feeder cattle program was to allow animals ultimately destined for slaughter to be imported into Canada year round without testing for blue tongue and anaplasmosis. In response to repeated industry demands and the use of scientific-based risk assessment, Canada’s import requirements for U.S. feeder cattle have been modified several times. In 2004 we dropped blue tongue testing from 39 low/medium incidence states and anaplasmosis testing from any state under conditions of a permit, which eliminated the need for antibiotic treatment. Although breeding cattle were initially excluded from these provisions, appendices to the “restricted feeder” import regulations allow low-risk movement of cattle imported as feeders into the national herd under special permit and testing protocols.

The tendency to gamble on the side of risk for the sake of short-term commercial gain can be habit forming. We must remain vigilant that risk associated with diseases whose dynamics constantly change is critically assessed and adjustments made as necessary. There’s no future in replaying old mistakes.

Dr.RonClarkepreparesthiscolumnonbehalfoftheWesternCanadianAssociationofBovinePractitioners.SuggestionsforfuturearticlescanbesenttoCANADIANCATTLEMEN ( [email protected]) orWCABP ( [email protected]).