It’s up to players in the Ontario and Quebec ag sector, especially the hog industry, to make sure the two provinces’ new “joint action plan” on agriculture amounts to more than just a “vague resolution” to chat once a year, the George Morris Centre says.

The Guelph-based ag think tank last week released a new report which sees “significant potential for co-ordinating policies that address issues affecting agriculture and agri-products in Eastern Canada” coming out of the joint plan developed earlier this spring.

“The challenge to industries in the two provinces is to leverage the opportunity to initiate needed change that provincial or regional politics might otherwise render unattainable,” Al Mussel, Ted Bilyea and Bob Seguin wrote in their report on the Ontario-Quebec Trade and Co-operation Agreement, signed last September, and the agri-products joint action plan that followed.

Read Also

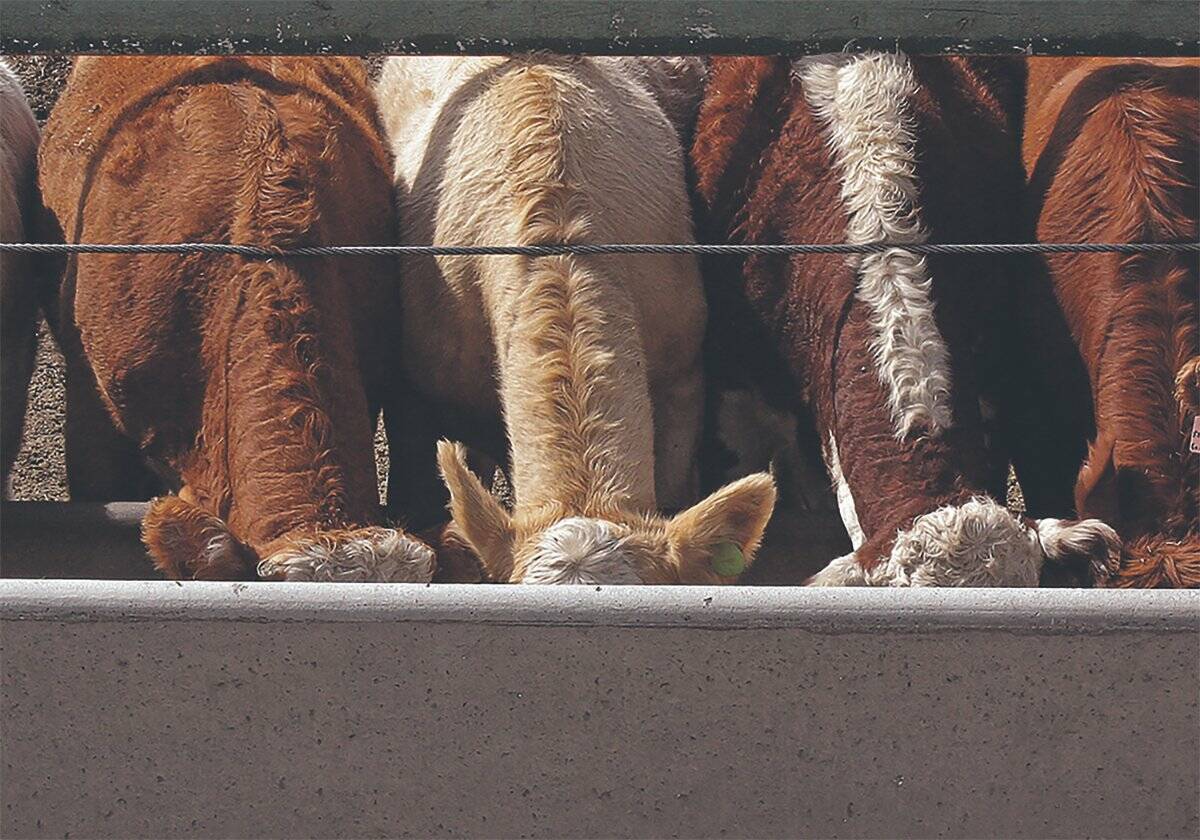

U.S. livestock: Cattle futures sink on concerns over Trump’s push to lower prices

Chicago | Reuters – U.S. cattle futures tumbled on Monday, extending a steep slide after President Donald Trump complained last…

“Thus, it could be an important opening for industry segments to propel policy innovations.”

The greatest need and opportunity are in the pork sector, the authors note. “Based on the existing trends in Ontario and Quebec, one or more plants in the two provinces are poised to close as the regional hog supply shrinks. Without any further planning or co-ordination, this contraction in processing could be exceptionally disruptive, and indeed destructive.”

Closure of a major packing plant in Ontario would “dramatically reduce” demand for live hogs in Ontario, boosting Ontario producers’ hog marketings to Quebec and/or the U.S., the report said. “This reduction in price would lead to a series of further decreases in Ontario hog marketings, and claims against safety net programming.”

Also, if related exports to the U.S. rose coinciding with safety net program payments, “the prospect could exist for a U.S. trade action, exacerbating the suffering in the Ontario hog segment. The analogy to a downward spiral is evident.”

Logically, the report suggested, the Ontario and Quebec pork industries could jointly ask:

- Given the apparent shrinkage in the sow herd and hog marketings, how much primary pork processing capacity is needed in Ontario and Quebec?

- How can Ontario and Quebec industries co-ordinate in this orderly consolidation of capacity?

- What new investments are required, and how can Ontario and Quebec governments act to facilitate these investments?

“Engaging this issue in isolation would be dangerous for the two provinces,” the report said. If Quebec stuck to the notion that its pork processing capacity should match its historical hog marketings, and Ontario reciprocated, it’s possible or even likely that the two provinces would renew their respective hog processing infrastructure, each with too much capacity.

The two provinces “have created a potential opening for industry to co-ordinate and bring forward solutions, which could address important issues,” the report said. “It is left to them to do so.”

Yogurt composition

The report suggested the two provinces could also gain from co-ordination on compositional standards for yogurt, whereas Quebec has developed its own, to limit the use of milk protein isolates (MPIs) as a substitute for non-fat milk solids.

Even though Quebec remains Canada’s main yogurt producer, there are still “distinct disadvantages” to a provincial standard, the report warned. Yogurt imports can’t be bound by the Quebec standard, and if Quebec’s processors see the provincial standard as onerous, yogurt production could be shifted elsewhere.

“Most importantly, the development of unilateral provincial standards does not address the issue of competitive pricing by milk class and component that leads processors naturally into compliance,” the report said.

“Industrial milk pricing issues cannot be resolved unilaterally by a province,” the report suggested. “They must devolve to regional pools and ultimately to the national level as they are impacted by support prices.”

Egg, poultry trade

Also, the report noted, allocation of a national market across provinces in poultry and eggs has created “tension” in poultry supply management. As it now stands, while the national market can grow, the national market share of one province relative to another cannot.

“The potential for friction associated with this system is exacerbated by the move toward processing supply assurance in many provinces,” the report said, in which case a given plant becomes “entitled to its historic share of provincial production.”

Thus, the report said, it becomes difficult for one processor to grow relative to other processors in a province, without having to buy plant supply assurance entitlement from rival processors, or buy farm product from a province next door for processing.

“This is especially significant in Quebec and Ontario, where there is a high density of processors and producers, and no major physical barriers to interprovincial transport,” the report noted.

Marketing boards have only “limited” authority against interprovincial movement. Furthermore, unlike dairy, the regulatory basis for interprovincial pooling doesn’t exist and the practice of cross-border procurement by one province from another “almost invariably leads to a reciprocal response as the selling provincial market is shorted.”

Marketing boards are “reduced to blunt instruments” to try and control this behaviour, the report said. Dealing with these issues at the regional level, rather than the provincial level, “could recast the discussion away from a reactive zero-sum game and toward a more collaborative resolution.”