Glacier FarmMedia—Agriculture across the globe is closely linked to La Niña and El Niño when it comes to setting the weather stage for the next growing season.

“I’ve got the sun to work with, I’ve got the atmosphere to work with and I got the ocean to work with. Those are the biggest drivers that I use,” Matt Makens told the recent Alberta Beef Conference in Calgary.

“For Western Canada, definitely the States, definitely Mexico, definitely South America, absolutely Australia, this El Niño/La Niña thing is the second biggest driver of weather. What’s number one? The earth’s tilt, seasonal change.”

Read Also

Prairie forecast: A temperature rollercoaster and the possibility of snow

Prairie forecast covering October 8 to 15, 2025. The Prairies may be in for a prolonged battle between warm and cold air before winter sets in. This could bring lots of rain or snow.

What are La Niña and El Niño?

La Niña and El Niño events typically occur every two to seven years but occur on a regular schedule.

El Niño events can last for nine to 12 months but sometimes it can be for years. La Niña can last for up to three years.

El Niño refers to the above-average sea-surface temperatures that periodically develop across the east-central equatorial Pacific Ocean, while La Niña refers to the periodic cooling of sea-surface temperatures across the east-central equatorial Pacific.

Makens, who runs of Makens Weather, has presented thousands of weather forecasts and outlooks to dozens of industries since the 1990s, with a primary focus on long-term seasonal forecasts and short-term weather hazards for the agricultural industry.

His company serves global clients from Australia to Canada and throughout the United States, including CanFax, CattleFax and the National Cattleman’s Beef Association.

He said La Niña used to be a fantastic snow producer for Canada. During La Niña events, trade winds are even stronger than usual, pushing more warm water toward Asia.

Off the west coast of North America, up-welling increases, bringing cold, nutrient-rich water to the surface.

During a La Niña year, winter temperatures are usually cooler than normal in Western Canada, but not so much in recent years.

Warmer than average temperatures indicate an El Niño, while cooler than average temperatures indicate a La Niña. Their effects are close to mirror images in different parts of the world.

“If you hear La Niña in Canada, a snow producer. If you hear La Niña in Texas and Mexico, it’s drought. South America, if you’re in Brazil, northern Argentina, La Niña brings drought. If you’re in Australia, La Niña brings water a lot of the time,” said Makens.

A warming ocean

A mere fraction of a degree change in temperature in the oceans can change the impact of how moisture is spread across the landscape, changing the orientation of moisture and drought and cold and hot.

Ocean temperatures have been steadily rising for decades, with the rate of ocean warming doubling in the last 20 years.

NASA reports that the last 10 years were the oceans’ warmest decade since at least the 1800s, and 2023 was the warmest year on record for the global ocean. Satellites, buoys and other monitoring systems are used for ocean temperatures, from which meteorologists gleam information.

Makens presented decades of statistical data since the 1950s that show the extreme outcomes when La Niña and El Nino temperatures go to plus two C and minus two C . This year, the La Niña went down to -1.1 which is defined as moderate.

“It didn’t maintain. Why did we see these wild swings of cold and warm, cold, warm? It’s because the atmosphere never fully embraced this La Niña. It did it three times — September, December and February is the only (time) the atmosphere acted like La Niña. In Canada, we fluctuated between the La Niña side and the neutral sides,” said Makens.

In terms of frequency of drought, ocean data has shown since the late 1990s that droughts are going to occur more frequently and rapidly according to Makens’ models, which is part of a cycle over the last 150 years.

Soil moisture should start well

However, relief may be coming for producers, particularly those who raise cattle.

“If we are going to rebuild the herd, are we going to have the water to do it? If these things are so slow to change, how do we get that frequent moisture in across the States and in parts of the Prairies and down through Mexico, how do we get to that point?” Makens said.

“Should history repeat itself, it should be within five years. The oceans have to behave like we expect them to behave. We’ve melted a lot of ice, so that water in the ocean, that changes its salinity, it changes a lot of the characteristics of the ocean. I think what happens long term is that the frequency of these wet periods is not going to be 20 to 30 years anymore. It’s going to be shorter and we will go back to the more frequent 20 to 30 years of drought.”

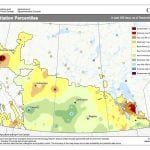

He expects soil moisture to start off the spring well for producers, but it will not be sustained as the situation quickly changes going into summer.

“Your transition will be quicker to drought this year than it was last year. That also means, conversely, it will warm up faster than it did last year.”

Makens said a flash drought is characterized by a rapid onset, intensification and severity over a relatively short time frame of a few weeks.

“There will come a point in late June or July where you will hear about this drought and its impact on U.S. corn, and it will impact you as well,” said Makens.

‘Encouraging’ snowpack

He said data from the 1950s shows we should plan for another neutral La Niña pattern, similar to what was just seen in Western Canada.

“Does that mean we are going to have great snowpack? I would like to say yes, that’s usually what we get with an La Niña winter, but we need it t0 be a stronger one (La Niña).”

If La Niña holds at least into the neutral grouping, it will be advantageous for snowpack and water because colder weather will hopefully lock it rather than the radical ups and downs of the past year bringing rapid changes.

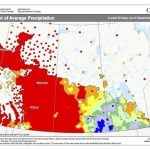

Makens said precipitation was sporadic between December and February with the mountain snowpack remaining below average. Soil moisture levels in most cases support starting the growing season on a sound footing, with data indicating a rapid decline in soil moisture in the months ahead.

During question period, producers asked about predictions further north in the province past Edmonton.

“The current snowpack is encouraging, and moisture trends will favour that area in northern parts of the province and northern Saskatchewan,” he said.

“The precipitation in those areas will be very close to pollination, whereas the south side is going to dry out too fast. So for northerners, the outlook is actually much more positive than the south.”