It can be a challenge to get first calvers rebred without losing ground. They often calve later the next year or come up open. The two-year-old is nursing a calf, still growing, and needs good nutrition and body condition to cycle on schedule after calving. Two-year-olds need more care and management than mature cows.

Dr. Steve Hendrick, Coaldale Veterinary Clinic, Coaldale, Alta., says a lot of ranchers try to help heifers by breeding them early, ahead of the cow herd, so they will calve earlier and have more time to recover from calving before they rebreed.

Read Also

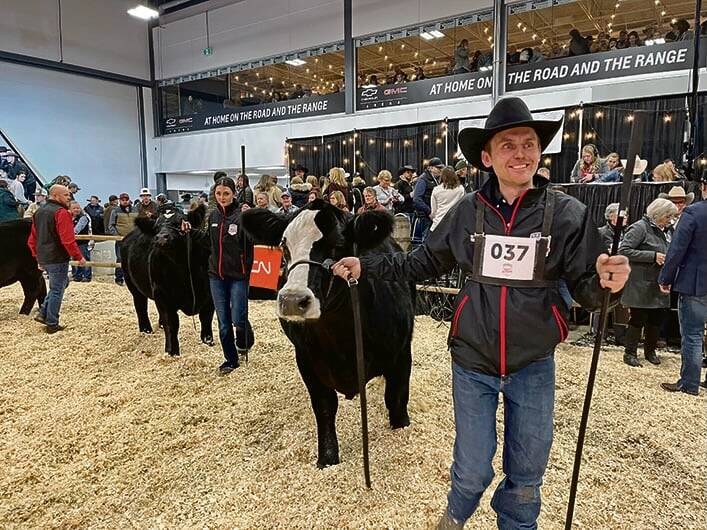

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

Dr. Colin Palmer, department of large animal clinical sciences, Western College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, says heifers tend to have a longer post-partum recovery period than cows and are slower to start cycling again after calving. “To overcome that, some ranchers have heifers calving one cycle length (three weeks) earlier than the cows — to give them more chance to breed back on time,” he says.

Selecting replacement heifers that were born early also helps. This not only means they are a little older than the average heifer calf and more likely to breed, but they are offspring of your most fertile cows — the ones that breed early. “You perpetuate fertility, as well as having that extra time for them to grow,” Palmer says.

“There are two main things that determine cyclicity in heifers. One is age and the other is body size and condition. Larger body size goes along with older animals, but feed can also play a role. We used to talk about feeding heifers to reach about two-thirds of their mature size before their first breeding season. But work done by Bart Lardner and Kathy Larson at Western Beef Development Centre found that feeding to 55 per cent was adequate in their Angus-based breeding herd. Their long-term work showed no negative effects, so you can feed heifers to lighter weight, if you make sure your feeding program is sufficient to achieve the target,” says Palmer.

“Some of us in extension are a bit careful about recommending that strategy; however, since we feel that many heifers are only being grown to about 55 per cent anyway, even when we were recommending 65 per cent, so we worry that the industry might try to cut them back to 45 per cent,” he says.

“We don’t have to push heifers to 65 per cent of mature body weight to breed, and we don’t want to overfeed them. Getting heifers too fat, beyond two pounds-per-day weight gain, can lay down too much fat in the udder — and they won’t milk as well. It’s best to have a slow and steady growth, in moderation,” says Palmer.

Age and nutrition play a role in puberty, as does sire’s scrotal circumference. “The most fertile heifers are often sired by bulls that have greater scrotal circumference. Early puberty is heritable. Scrotal circumference is a good indicator of early puberty in bulls, and their daughters,” he says.

“Heterosis also plays a role in fertility; crossbred heifers are more fertile than purebred heifers,” says Palmer.

“Another thing that can help first calvers is to manage them separate from the mature cows for winter feeding. They don’t compete well with larger, more dominant cows. If you can’t keep them in a separate group, however, there are ways to manage the feed so they have more chance to eat it,” he says.

“I run first-calf heifers with cows, but we try to distribute the feed evenly. Rather than using bale feeders, where there might be a bunch of cows eating the best bale and keeping the others away, we roll out the bale so it’s spread farther. There’s more chance for them all to eat it. We also changed our mineral feeding so it’s in long troughs rather than just a few tubs.”

“There was some work done here in Saskatchewan that found young cows tend to be more deficient in copper — which plays a big role in reproduction. We wonder if the young cows weren’t able to compete for their share of mineral supplementation. It’s important to make sure young cows have access to supplement and that they are in decent body condition by the time they hit the breeding pasture,” Palmer says.

Make sure they are not too fat nor too thin. On a body condition scale of five, they should be at a 3.5 to four on that scale, before calving. “It’s very hard for them to keep up, after calving,” he says. They need the best hay and the best pasture between calving and rebreeding.

It also helps to use easy calving bulls for heifers. Their recovery after calving will be quicker if they can calve easily. “Cows or heifers that have a difficult calving have a longer recovery phase before they can start cycling again,” says Palmer.

“In dairy herds we see a lot of sexed semen being used on heifers, to produce heifer calves,” says Hendrick. “Even though pregnancy rates with sexed semen are not as high as when using regular semen, the pregnancy rates with heifers are often a little better than cows and it’s worth that investment on heifers. If you’ll have heifer calves (which are generally smaller at birth than bull calves), they will be more easily born. Sexed semen is not used as much yet in the beef industry, but this is something that might be a factor in future,” says Hendrick.

“There are also a number of drugs and protocols used for heat synchronization in heifers, to get them all bred quickly and at the same time. We used some of these in a heifer project Bart Lardner was doing at the University of Saskatchewan. When we first proposed that project, and were deciding whether to utilize some of these reproductive drugs and tools, it was interesting to hear comments from producers. A lot of them were very hesitant about it, thinking these were too much of a crutch to get heifers bred early,” says Hendrick.

Many producers want breeding to be part of the selection process for sorting out the most fertile animals to go into the cow herd. “This is a good point. If you are keeping every bred heifer, even if they caught late, it’s no wonder that they fall out of the program and don’t breed back for their next calf,” he says.

Often it’s better to use “survival of the fittest” as part of the criteria for which ones become cows. When you expose the group to a bull, the ones that breed early are the ones you want to keep. “Many ranchers put the bull in for just one cycle, or a cycle-and-a-half (or two at most), and sell the heifers that don’t breed in that time frame.”

Heifer development research

Dr. Bart Lardner, Western Beef Development Centre, recently did a project on developing heifers. The way heifers are developed is important because the body condition they have at first calving makes a difference in whether or not they will cycle on time to breed again.

“Our objective in this project, however, was looking at developing heifers in an environment where we are expecting them to prosper as mature cows. We developed them in an extensive grazing winter system — from weaning until their first breeding season the following year — rather than in a feedlot. We were also developing them in two groups, at two different target weights pre-breeding. We looked at getting one group up to 55 per cent of mature body weight versus another group at 62 per cent of mature weight,” says Lardner.

“We followed these heifers all the way through their first, second and third calving, because a lot of the earlier work on heifer weight development only followed heifers to their first pregnancy diagnosis. We kept tabs on them longer because we wanted to see if developing them to 55 per cent of mature body weight before breeding would have a negative effect on reproductive efficiency. In fact, we didn’t find any difference (in future reproductive success) in terms of whether we developed them to 55 per cent or to 62 per cent of mature body weight,” says Lardner.

“Our conclusion is that maybe we shouldn’t be trying to develop heifers in a feedlot environment to get higher rate of gain that first winter, to have them weighing more at first breeding the next summer. They are never going to see that type of diet, ever again, as mature beef cows on a ranch in Western Canada. We use an extensive system in Saskatchewan, bale grazing. We’ve found that heifers developed to 55 per cent of mature weight were no different in pregnancy rate for their first, second and third calving (and there were no negative effects on performance of the calves born from these heifers), compared to heifers developed to 62 per cent of mature body weight,” he explains.

“We were also looking at longevity, and found that 78 per cent of the cows that were developed to 55 per cent of bodyweight as heifers were retained in the herd after three years, and 76 per cent of the 62 per cent bodyweight heifers were retained after three years, so there wasn’t much difference. This gives ranchers alternatives on growing their heifers.”

The main thing Lardner recommends for ranchers developing heifers to 55 per cent of mature weight by first breeding is to make sure the quality of the breeding pasture is adequate to meet the requirements of heifers that are still growing. “Prior to that first calving, we also put those pregnant heifers on a diet with good-quality roughage — such as a mixed grass/legume hay,” he says.

Other strategies

“This can help make sure they are ready to rebreed and that we don’t lose them out of the herd as first calvers. They are less likely to come up open. You have a lot of development costs invested in a heifer, and don’t want her to wash out after just one calf. Our beef economist, Kathy Larson, has done some work looking at how many calves it takes to pay for development costs on that heifer. A few years back it was three or four calves, and in today’s economy it’s more like five or six calves before the heifer pays for herself. So we want that heifer to stay in the herd long term.

“We are doing another project right now, though it’s a strategy a rancher might not do, to make sure first-calf heifers get rebred. We are looking at providing heifers with an energy supplement that differs in type and form of fat from most supplements, and providing this from calving until breeding. We are sourcing two types of fats, looking at mono versus polyunsaturated fats from either canola or flax. These are both common crops in Western Canada. We are looking at whether fat in the diet will improve conception rates for that second breeding season,” says Lardner.

“This is one more strategy a person could try, but we don’t have results yet. As a research facility we are always trying to investigate ways of feeding heifers,” he says. If heifers are kept separate from the older cows, the heifers could be fed the fat supplement without having to provide it for the whole herd.