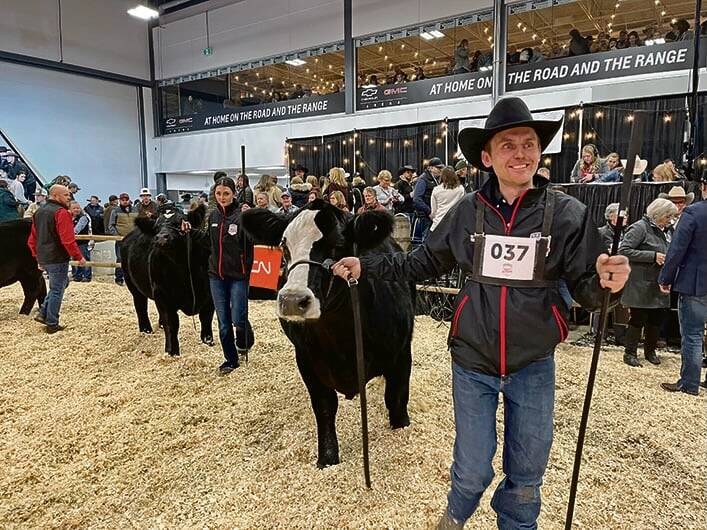

Matthew Ramsey would much rather calve in January than in April.

At least in January, he says, you know what you’re getting into.

“We got to the point where April sucked every year,” he says.

Read Also

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

“Eventually, we came to the conclusion that we weren’t happy with April, we’re either going to go earlier or later to avoid the April wet and snow and just unpredictable weather.”

April’s weather can be variable anywhere in the Prairies, but even more so in Manitoba, where the Ramseys’ operation, Lazy J Ranch, is located. While Saskatchewan and Alberta are a little drier, Manitoba often has wet springs, with areas prone to flooding as months of winter snow melts.

Ramsey runs a herd of 400 head with 60 purebred Charolais near Hamiota, Man., with his wife, Sarah, and their three children. They also farm 1,000 acres of grain and run Rammer Charolais, the purebred division of their ranch.

Producers who calve in the winter usually do so if they run a mixed operation, as the calving season wouldn’t interfere with cropping. Calves have extra time to put on weight before sale. As well, purebred producers often calve in the winter to reach production targets.

[RELATED] Contracted and lax tendons in newborn calves

Pros and cons

Ramsey says there are pros and cons of calving in the winter.

A pro is that the weather in January is more predictable — producers who calve in the winter know the weather will be cold and that calves need to be born in the barn as a result. In comparison, calving in April has unpredictable weather, often with rain and snow in tandem, and calves spread out.

In January, all the calves are in the same areas, so are easier to manage.

“If there’s a problem with calving, or with a calf not nursing or something like that, you can rectify that problem in minutes,” Ramsey says.

However, producers who calve in January must have the right facilities to ensure calves are born into a warm environment and survive. Having previously calved in April, Ramsey didn’t have the right facilities to move his calving season to January, so they built a barn when they took over the purebred herd.

“As we continually moved more and more cows early, we expanded our barn and erected some loose housing sheds for those young calves so in the winters they can be out of the wind,” he says.

Dr. Karin Orsel is a veterinary epidemiologist at the University of Calgary’s faculty of veterinary medicine.

She says it’s important for producers who are winter calving to stay on top of the calving season to ensure calves are getting the care they need. These include shelter, windbreaks, dry bedding and colostrum.

“I think for me it’s thinking about that early intervention,” Orsel says. “And shelter, and bedding, and colostrum, those were the most important things I tend to talk about with producers.”

Extreme cold

On Lazy J Ranch, not a lot changes when an extreme cold warning comes in. Ramsey says there are subtle differences. Usually, they have 50 cows in the barn, but when it gets really cold, he says they’ll have closer to 75.

“Those calves that are born in a real bitter cold, they end up staying in the barn for a prolonged period of time,” Ramsey says.

Ramsey says that although he wouldn’t have a calf outside shortly after birth, a calf that is two or three days older can better withstand the elements.

“Usually once they’re outside for a day or two, they’re pretty good,” he says. “And so if they’ve already gone out and are doing well we’re not worried about them.”

Even in extreme cold, calves who have left the barn don’t have to come back to it, unless they left as soon as the extreme cold started. Calves that remain outside in the cold are kept warm by fresh, clean bedding, shelters and windbreaks, and sunshine.

“Even if it’s minus 35, it’s amazing how warm it is in the straw out of the wind,” Ramsey says.

Orsel says in really cold weather, the most important thing is to keep a newborn calf warm.

“The calf that is wet is getting cold really fast, so it will burn off all its reserves just to stay warm,” she says. “So the energy needs are extremely high. And the risk of freezing is very, very evident as well.”

Orsel says producers should make sure calves stay dry in extreme cold — whether that’s by using a calving shelter, fresh bedding or colostrum. She also says that if a producer knows a period of extreme cold is coming, they should take time to prepare, considering things like how easy it will be to access the calves and how many hours of daylight you have.

It’s important to think about the logistics ahead of calving, she says. Consider where the cows calve, where you can move the calves to and whether you can bring them to a cleaner area or an area with less snow.

“If you have a heifer that you’re worried about, can you bring her closer to light? Can you bring her closer so that you can keep your eye out on her?” asks Orsel.

Disease

Another issue that can arise from having cattle in such close quarters in a calving barn is the spread of disease. When animals are packed together tightly, diseases can spread more easily than if cattle are spread out.

“I think my challenge is always with a shelter and especially if it’s a barn, that the calving barn is also used as a sick pen,” Orsel says. “And that’s always a challenge because now you have your highly susceptible animals combined with the animals that most likely shed. And that’s an issue.”

Orsel says having a separate area in the barn, or even a separate shelter for sick livestock would work best in preventing disease spread.

Another consideration when it comes to calving in the winter is scours, an illness that affects calves and causes diarrhea. In extreme cold, this could freeze. If the calf becomes weak, it’s “super susceptible,” says Orsel. Plus, bringing that sick calf into the barn could expose the other susceptible young calves to the bacteria, virus or parasite that infected the initial calf.

Colostrum is an efficient way to give calves born in the winter the nutrients and antibodies they need to stay healthy — in the winter, calves will need more energy to maintain their body temperature. Colostrum is also an effective way to keep calves warm by providing the energy and comfort they need.

“We’re pretty diligent about making sure they get colostrum in the first few hours of life and they’re sucking good,” Ramsey says.

Frostbite

Another issue that can arise when calving in the winter is frostbite.

Ramsey says this is something they struggle with on their operation. He says wind is usually the main cause.

“If a calf lays out in front of the shed or the wind blows on his ear or if his mother licks its ear, that we definitely struggle with,” Ramsey says.

Sick calves are also susceptible to frostbite.

“They don’t need to have much of a fever to then freeze their ears. It seems like any fever at all, they can freeze their ears,” he says.

Both Ramsey and Orsel stressed the importance of dry bedding to prevent frostbite.

“We talk bedding, bedding, bedding — get them dry,” Orsel says. “Having bedding available is super important.”

Despite the challenges, for Ramsey, winter calving is the way to go, with the more predictable weather — even if it’s -30 C or below. It’s important to give the calves the resources they need to withstand the elements.

“They’re remarkable little creatures once they get to be a day or two old,” he says.

“It’s amazing what they can do — and maybe not one day old, but certainly when they’re three days old — and they get outside in the sunshine and they’re running around even if it is minus 30.”