With virtual fencing companies gaining steam, it is important to know the work that is being done in Canada

Virtual fencing is growing rapidly as more companies are sprouting up with variations of the technology and more trials are happening across the country.

For producers interested in adopting virtual fencing, understanding the differences between technologies, Canadian research and associated costs is crucial.

Vence

Read Also

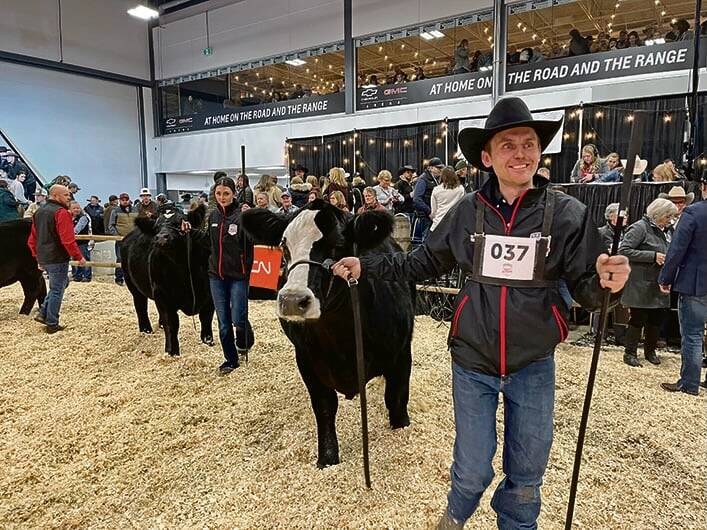

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

In 2022, the Saskatchewan Stock Growers Association were looking for a producer interested in trialling virtual fencing technology.

When John Chuiko heard, he decided to get involved in the trial. Now, this virtual fencing technology has changed how he and Deanne do things on their operation.

The technology being trialled on the Chuiko’s operation, CJ Ranching, in northwestern Saskatchewan, is from Merck Animal Health, and known as “Vence.” With this technology, cattle wear collars that emit GPS signals and users can set up virtual fences from their phone or computer. Solar-powered base stations remotely manage the collars. The collars, however, don’t use solar-powered batteries — instead, they use regular batteries, as Vence believes they are hardier.

Currently, CJ Ranching is the only place in Canada with this technology from Vence. They have done one year of the trial and are going into their second and last year, though they are hoping to extend the trial.

“The potential is only bound by your creativity,” Chuiko said.

There was a learning curve for both the Chuikos and their cattle.

“There was just lots of stuff to figure out. But Vence was so good. There’s a support team, you get a ‘rancher success’ person that helps you along with the tech, and she was so good. So it was just a matter of learning the software,” Chuiko said.

The cattle have to be trained with the technology, as well. There is a four-day training period where the producer, alongside their ‘rancher success’ contact, creates virtual fences along a physical fenceline. Gradually, the virtual boundaries move inward from the physical fence until, by day four, they are near the middle of the paddock. A warning beep is emitted from the collars when the cattle get too close to the virtual fenceline, and a shock if they get even closer.

Northern Saskatchewan trial

The trial started in full force in the spring of 2024. The main thing Chuiko was hoping to get out of it was the ability to manage his cattle in his vast forest lease and to rotate his herd through the pasture. He rotates his cattle between one to six times a day to mimic nature. It is important to the Chuikos to prioritize the health of the land.

“Our forestry lease is very high labour and very intensive. So, the potential for this is pretty huge for us,” Chuiko said when he presented at the Saskatchewan Stock Growers AGM in June 2024.

As the only people trialling this technology in Canada, the Chuikos ran into a few challenges. One of the big ones is collar lifespan and retention. Throughout their breeding season, only two of their 15 bulls kept their collars. Seven per cent of their cow herd lost their collars throughout the year. Signal errors affected 32 collars and another seven per cent had critical battery health by the end of the fall.

“The things that we learned from last year would be battery life seems to be a little bit of a challenge for us.”

They also realized their base stations couldn’t just stay in one spot due to their forested lease and how much their cattle move. To combat this issue, Chuiko put their base stations on trailers and move them to the cattle as needed.

“As soon as we did that, our communication got way better again. So there are definitely some challenges that we face, but we feel like we have an opportunity to kind of alleviate these and be better again this year.”

The Chuiko’s forestry lease is 7,500 acres, making it hard to build a fence and manage their herd. Virtual fence is a game changer when making use of this part of their operation. Now they can not only make better use of their land base but focus on soil health and taking care of the grass.

Though the biggest benefit for the Chuikos is in their forestry lease, Chuiko can see potential uses for producers who are using this technology on the flat prairie.

“I think there’s lots of potential for this type of technology going forward.”

Moving into the second and last year of the trial, the Chuikos have plans for what they want to try to examine this year for the virtual fence. They want to figure out what can be done to make the collar batteries last longer. They also want to try the technology for different applications, such as corn grazing, stubble grazing or sorting cattle.

At the Saskatchewan Stock Growers Association’s AGM in June 2024, Chuiko highlighted other potential applications of this technology he is interested in — for example, monitoring bulls to see who is performing and who is lying around.

The program is a subscription model and costs US$50 per collar per year. Base stations are purchased and cost $13,000 each.

Currently, the Chuikos have three base stations and over 400 animals they have collared. They have money invested in this trial alongside the Saskatchewan Stock Growers Association and the Saskatchewan government.

eShepherd

Gallagher launched their virtual fencing system, eShepherd, a year ago in the North American market. In their first year, Gallagher has acquired 40 to 50 new customers in Canada.

Sharl Liebergreen, the general manager of eShepherd, sees interest in virtual fence in the North American market.

“Flexibility, for sure,” he said of the benefits.

Producers can use virtual fencing for many things. Commonly, it is used for rotational grazing or to make better use of pasture land and cropland with cattle. Some users are getting rid of internal fencing and cross fencing altogether and moving to just virtual fence.

During times of disaster, virtual fence is a benefit, as well.

“In your part of the world, British Columbia, Alberta, where there’s been enormous forest fires, there simply are no fences left. And so (virtual fence) is a really big advantage,” Liebergreen said, adding that “even if you could find the labour to get out there and spend all that money building fences, you can now use a different type of technology to replace that permanent infrastructure. So that’s a big win.”

EShepherd consists of collars the cattle wear that connect to GPS and cell service so users can create virtual fences directly from their phones. The collars emit an audible beep when the cattle draw close to the virtual fence, and then a pulse when they get closer.

The fences are set up in one of two ways — through cellular data service, or through base towers that help emit a stronger signal. Gallagher will help farmers and ranchers determine which will work, based on their operation size and what they need.

“We begin by asking many questions. We really want to understand basically the lay of the land. How strong are the cellular providers in that area? Is it mountainous? Is it flat? Oddly… the very flat land actually gives us a few problems with the base stations. We want to try and get a bit of altitude. But we ask as many questions as we possibly can about the land, but also about the intentions of the customer.”

With multiple customers already in Canada, Liebergreen is confident that the battery will withstand a Canadian winter. Because the batteries are solar-powered, the only issue they have run into is the amount of sunlight the batteries get in the winter — they are fine with most normal winter days but can struggle with fog or prolonged cloudy periods.

There are some similarities between eShepherd and other virtual models, but some important differences as well. A big one is eShepherd is a purchase model, unlike Vence, which uses a subscription and rent model for the collars.

With eShepherd, each collar costs around $350. The base stations are around $6,000 each. There is a service charge of $2.50 per head.

Liebergreen said the collars are long-lived devices and will last many years.

After the first year of operation with eShepherd, there are plans to adapt and update the product in the future. Currently eShepherd has free updates every two weeks, but Liebergreen said there will be bigger changes coming down the line.

“I think in the future, there will be other things that we want to introduce which may come with a charge but right now, we are very focused on virtual fencing.”

More virtual fencing options

NoFence: A virtual fencing system from a Norwegian company, which comprises collars worn by the cattle and an app downloaded to a phone or a tablet that communicates over a mobile network. Producers create virtual fences in the app. The University of Alberta trialled the technology in 2023 with 39 to 49 heifers collared, depending on the year. Lakeland College also trialled NoFence, focusing on how it performed in a Canadian winter. NoFence collars for cattle cost around $329 each with a monthly subscription fee on top of that.

Halter: Based out of New Zealand, this technology has started to expand in North America. Halter consists of collars, towers for the mobile signal and an app. Halter has a team of experts who help producers map their farms, determine what they need, and help train the herd. Halter has only recently expanded to the U.S. and has not been trialled in Canada yet, though there has been interest from research institutions such as Olds College.