Looking at the risk budget for newborns brings to mind the adage “I am what I do.” Organizations grow around ideas and things that get done, not people. The adoption of new tools and technology strengthens the industry’s unflagging resolve to improve animal health and welfare. Getting a running start on health starts with nutrition, something that — other than handling colostrum intake — has long been overlooked in newborn beef calves.

Consumer attitudes about where their food comes from get linked to how it’s produced. They’ve been focused on industry’s ability to address questions related to pain relief and stress in young animals. Nutritional supplementation for the neonate is now being seriously examined.

Read Also

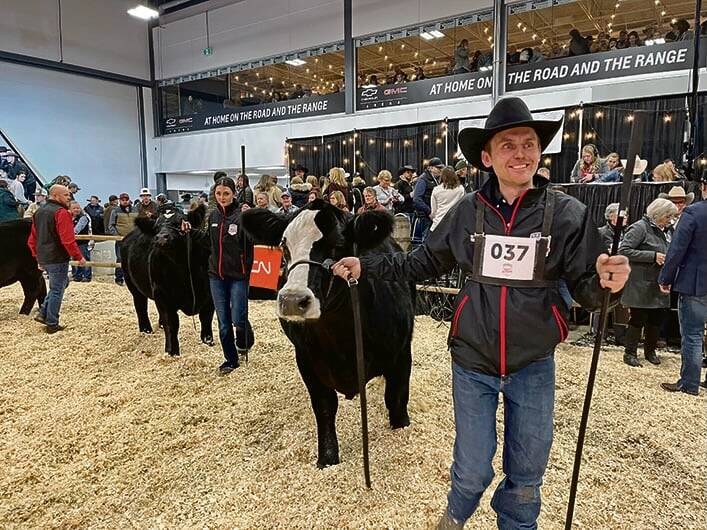

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

The term “neonate” defines calves under 28 days old. During the neonatal period, the calf faces high risks from a host of infectious diseases. Neonatal morbidity and mortality cause huge economic losses. Taking stock of what is provided as nutritional supplements to newborn animals is often overlooked outside of vitamin E/Se in deficient areas, vitamin A supplementation of the brood cow and management of colostrum intake at the time of birth.

The main objective of cow-calf systems is to produce the greatest weight of weaned calf per bred cow. Nevertheless, top beef-producing countries in some cases achieve only about 50 per cent above what gets weaned. Common causes of lower weaning rates and overall production faults often start with the breeding season. During this period, cows are usually in suboptimal body condition and exposed to environmental stress and infectious disease. Low pregnancy rates result.

The diagnosis of the cause of early reproductive failure can be challenging. Research articles report abortion and perinatal mortality vary between five to 12 per cent and two to five per cent, respectively, representing a huge loss of calves.

Managing neonate nutrition during the first month following birth can be another production challenge. Further investigation into the relationships between management decisions and calf health may guide the development of management practices and protocols to improve calf health, especially in compromised calves after a difficult birth. Production animals’ performance continues to evolve with genetics. As the nutritional demands increase, our neonatal animal management practices have not changed significantly over time.

I do not want to downplay the importance of colostrum. Colostrum is an extremely important source of immunoglobulins for newborn calves. Much has been written about proper colostrum feeding and management in the health of neonates. Less well appreciated is the role of colostrum in providing other important nutrients such as vitamins and minerals required for normal metabolic functions, growth and establishment of immune function. Nutrients such as vitamins A, D and E, B12, Se and iron are important. Colostrum remains the first source of protein and energy to the neonate. Colostrum’s role in providing other important nutrients varies depending on nutrition of the dam before calving, which is often less than optimum because of inadequate diets. As well, concentrations of nutrients often rapidly deplete following parturition. It’s important to remember:

- Mother’s milk is deficient in many vitamins and minerals to meet the full nutritional requirements of neonatal ruminants.

- Key nutrients rely on colostrum transfer to the neonate, which is often imperfect.

- Nutritional content of colostrum varies significantly.

During the period from pregnancy diagnosis to calf delivery, efficiency of detecting etiological agents or disease entities remains below 50 per cent, even though many experimental models dealing with this topic have been developed. Low conception rates, subfertility and stillbirths in cattle frequently go undiagnosed. Moreover, even when disease control, management, vaccination and drug treatments are available, many risk factors — nutrition among them — still have a negative impact during the pregnancy and perinatal periods.

Animal welfare must also be taken into account in every livestock production system. Low reproductive rates (prolonged anestrus, low conception rates, high reproductive losses and high percentage of assisted deliveries and/or dystocia) may indicate animal welfare problems. Indeed, differential diagnosis is critical and essential to identify the causes of reproductive losses and perinatal mortality in cattle.

Most of the research in neonatal calf nutrition and subsequent development of the rumen and forestomachs has been conducted in dairy calves. Throughout the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, the primary objective of most calf research was how to wean healthy, adequately grown calves at an early age — generally less than 30 days. Research on issues with dairy calves continued to increase, evidenced by the publication of more than 580 articles in Journal of Dairy Science over the last 20 years. But little of it transferred to beef calves.

When calves are born, they have no innate immunity, nor are they functioning ruminants. They face the two major challenges of acquiring immunity and initially feeding as a non-ruminant while rumen development and function are established. A calf depends on colostrum from its dam to initially acquire immunity through absorption of antibodies before it later begins to synthesize its own antibodies. A calf’s liquid diet provides the majority of nutrition until the calf begins to consume enough dry diet, which will contribute to the development of its rumen and allow it to be weaned from the liquid diet. Feeding and management practices have changed substantially for dairy calves, but very little changed on the beef side.

Colostrum is recognized as a source of important nutrients for the newborn calf in addition to providing passive immunity. Limited placental transmission of fat-soluble vitamins is recognized. Dietary inclusion or injections are recognized as treatment options to treat important neonatal vitamin deficiencies. For example, vitamin A concentration in colostrum can be 10 to 100 times greater than that in milk produced later in lactation. Also at stake are the concentration of other important nutrients, among them vitamins D, E, B12 and iron.

The role of adequate vitamin and mineral nutrition in the health of very young beef calves is part of the “risk budget.” Specifics will be covered in my next article.