A wise old farmer once advised me, “Do what needs doin’, scratch what needs scratch’in. A good piece of advice as we look ahead to calving season and the grazing season beyond.

Being sure cows and bred heifers are fed properly through winter and later stages of pregnancy tops the list. Do this well and many other things simply fall into place.

Body condition plays a critical role in preparation for breeding season and rebreeding. The cow’s job in a commercial herd is to have a healthy calf, get rebred by 83 days post-calving, and wean a calf every 365 days. Thin cows (BCS 2) have a difficulty doing that. Increased calving difficulty when cows are in good condition (BCS 2.5) isn’t an issue.

Read Also

Effect of wildfire smoke on respiratory health in beef cattle

Of all domesticated species, cattle have the smallest relative lung capacity, making them particularly vulnerable to wildfire smoke.

Empty feed yards in the dead of winter come with huge economic consequences for individual producers.

Monitoring body condition of cows during gestation is closely linked to calving success and profit. Body condition impacts future reproductive performance, calf health, weaning weights, and overall herd productivity. Thin cows (BCS 2 or less) are only half as productive as cows in optimum condition (BCS 2.5-3). Producers should talk to their veterinarian about incorporating BCS as a tool in managing the cow herd.

Changing nutritional needs of brood cows and pregnant heifers during western Canadian winters can be a challenge. Feed analysis is needed for proper management of feed resources. Overfeeding is costly; underfeeding affects body condition and influences both short- and long-term performance of the breeding herd.

Adjustments to dietary protein and energy required to gain weight, should start no later than 60 days before calving. A full trimester (90 days) is better. Gaining weight becomes increasingly difficult and expensive as gestation progresses, especially when heifer growth through gestation is considered. Adding is very difficult when cows are lactating. Nutrient requirements increase 30 to 40 per cent at calving.

Inadequate nutrition during the last trimester of gestation affects birth weights, colostrum quality and immunity, reduced calf survival, decreased milk production, and reduced weight gain in calves — all the way out to weaning and beyond.

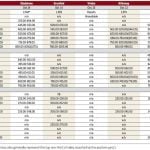

Winter-feed and forage-grazing costs account for 60-65 per cent of total cow-calf production costs in Western Canada. Cost-efficient winter feeding programs are important as long as reproductive potential is not compromised. It’s worth noting, that only 38 per cent of swath-grazed forage samples meet the energy needs of a cow through the last third of pregnancy (at -25 C) and only five per cent of those samples meet energy requirements in the last month of pregnancy. Cows relying solely on swath grazing often lose body condition through winter.

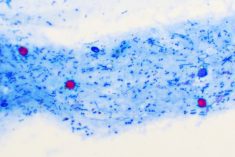

Over 90 per cent of feed samples contain detectable levels of mycotoxins, naturally occurring compounds produced by fungi growing on plants in the field or during storage. Managing risks associated with mycotoxins is important. It starts with knowing what mycotoxin is involved and levels contained in feed.

Fungi and moulds commonly detected in feeds include fusarium, penicillium, aspergillum, and ergot. Clinical signs associated with mycotoxin contamination can include feed refusal, unthriftiness, abortions, circulatory disturbances (ergot), and gastrointestinal disturbances. Nitrate poisoning has been associated with frozen green feed in silage and baled cereal crops. Mouldy sweet clover can cause severe hemorrhagic episodes in cattle.

Another important activity in the doin’ ledger is minimizing disease risk for newborn calves prior to and during calving season. Nowhere in cattle operations do basic principles of biosecurity come into play more than the time when highly vulnerable newborns get dropped into an inhospitable world of bugs and temperature extremes with a constant need for sustenance.

I consider the following ideas as common sense for disease control in newborn animals, but realize common sense isn’t as common as one might think.

Preventing disease isn’t about beating bugs — that’s impossible. Disease prevention, the underbelly of biosecurity, is about controlling the line of scrimmage between disease, host and environment. For instance, a calf is born with little immunity, then — in a perfect world — receives antibody-rich colostrum from a nutritionally fit cow in a clean environment. Volume matters: five per cent of their birth weight in colostrum before they are 12 hours old, or 1.8 to two litres for a 34-kg calf.

Pathogen numbers grow exponentially as calving season progresses. Space and simple hygiene become limiting factors. Simple things like keeping the udders of nursing cows clean and the calf’s environment dry and comfortable as possible are important first steps in controlling scours.

Calves from heifers face a greater risk of getting sick attributable to lower-quality colostrum, poor mothering skills and calving difficulty. Deal with these problems at the start of the calving season when things are the cleanest and the least harried.

The most important source of infectious organisms for calves is the gut of adult cows. The number of harmful bacteria, viruses and protozoa shed into the environment by cows steadily grows as calving season progresses. Sick calves become multipliers to countless billions of infectious organisms blanketing the calving environment. Calves born later in the calving season are exposed to higher levels of potential pathogens. Calves born later in the calving season face a greater risk of acquiring disease.

Cows and space can be effectively managed with programs like The Nebraska Sand Hills Calving System. The Nebraska system offers a basic way of effectively neutralizing extended contact among beef calves by: 1) using age to segregate calves to prevent direct and indirect transmission of pathogens from older to younger more susceptible calves, and 2) scheduled movement of pregnant cows to clean calving areas to minimize environmental contamination and contact time between calves and the larger portion of the cow herd. The primary objective is to recreate starting conditions of the calving season each week by having new calves dropped in uncontaminated areas, free of older, infective calves.