It was an anniversary of sorts this spring, with COVID officially turning four years old. Meanwhile, avian influenza leapt into ruminants, becoming known as bovine influenza A virus.

Globally, COVID killed over seven million. Where it came from is still debated by scientists, but probably from a Wuhan fish market in China and probably from eating an exotic species (bat?) that harboured the virus. Then sick people got on an airplane. The rest is history.

Sparring in scientific circles is relentless. Meanwhile, people still get sick. Mutation, adaptation and ineffective vaccination only help new strains evolve.

Read Also

Effect of wildfire smoke on respiratory health in beef cattle

Of all domesticated species, cattle have the smallest relative lung capacity, making them particularly vulnerable to wildfire smoke.

COVID became highly political very quickly. Discussions about simple things such as bed shortages in hospitals and the need for equipment and protective clothing consumed huge amounts of resources. Finding ways to equitably distribute needed medical supplies remained acute throughout. First responders were quickly overwhelmed. Discussion over the use of unapproved drugs to treat COVID flooded the media, including boastful remarks by then-president Trump, which added nothing constructive to the crisis.

I often wonder how countries would respond to a concurrent foot-and-mouth outbreak and if the swine and beef industry could survive. Always in the background: memories of the Spanish flu that killed an estimated 50 million people, or the carnage of the Black Death that killed somewhere between 75 and 200 million, enough to change the population dynamics of the world at the time.

African swine fever did raise its ugly head and caused severe shortages of pork in China, a primary staple for many.

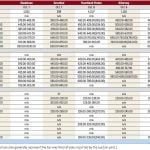

Then in late March, influenza was diagnosed in a wide swath of dairy cattle in Texas, Kansas, Michigan, New Mexico and Idaho, igniting concern. The situation is described as rapidly evolving. At time of writing in early April, one human had been involved, indicating possible transmission from animals to humans. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service published a paper on “frequently asked questions,” and I have tried to capture key points they made:

- Wild migratory birds are a likely source of infection (pigeons, blackbirds, grackles).

- A herd of baby goats in Michigan affected, suggesting other species could be involved.

- Transmission between cattle cannot be ruled out.

Initial testing indicates the virus has not changed, suggesting transmission to humans probably through direct contact with infected cattle.

Tests to date show the virus involved is H5N1, the same strain circulating among wild birds and commercial flocks.

Clinical symptoms include: fever, decreased production, off feed, consistency of milk changes resembling colostrum. Increased mortality has not been reported.

Although a significant percentage of cull dairy cows flow into beef markets, the USDA remains confident the meat supply is safe. Cooking kills the virus, as does pasteurization. Consumers are discouraged from drinking raw or unpasteurized milk.

A paper published by the Indian Journal of Medical Research in March 2021 reminded the world that the global increase in human-animal interactions and mixing of different species of animals in human-dense markets facilitates the emergence of novel viral diseases. Examples include severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), avian influenza A/H7N9 and H5N1, Middle East respiratory syndrome, Nipah virus disease, Ebola hemorrhagic fever and influenza A (H1N1). The paper is titled Increased human-animal interface and emerging zoonotic diseases: An enigma requiring multi-sectoral efforts to address.

COVID now joins the list of other massive outbreaks, epidemics and pandemics causing profound losses of human life and health, as well as economic damage. The COVID pandemic had affected more than 200 countries, with two per cent mortality, as of May 26, 2021. This highlighted the importance of reducing human-animal interactions to prevent such zoonoses. Rapid deforestation and shrinking boundaries between humans and animals create a crisis for natural habitation, increasing demands for wildlife products and extinction threats. Biodiversity loss compounds human-animal contact conflict. Large quantities of animal waste generated by animal agriculture amplify dissemination of zoonotic pathogens and facilitate zoonotic pathogen adaptation.

Public health systems face challenges containing epidemics due to inadequate understanding, poor preparedness and the lack of “One Health” approaches in surveillance and control strategies. Political commitment to build and sustain health-related programs is always guarded and slow to develop when needed. Because management measures are beyond the purview of health systems alone, policy adaptation in the face of pandemics is sluggish. The engagement of multiple stakeholders towards wildlife protection, land use, community understanding of agriculture needs, resource management and the concept of One Health is slow.

In 2001, the U.K. experienced the most serious epidemic of foot-and-mouth disease ever to occur in a previously foot-and-mouth disease-free country. Almost from the start, foot-and-mouth became widespread, with outbreaks from the north to the south of England, in southwest Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Between mid-February and the end of September over 2,000 outbreaks were recorded in Great Britain and four in Northern Ireland. Cumbria in Northwest England represented the epicentre. An additional 1,934 farms were subject to complete or partial animal slaughter. There were restrictions on public access, disruption to tourism and outdoor recreation. Some public services were badly disrupted. The entire eradication process faced sharp criticism. There were many lessons to learn and document. All this, without consideration of a concurrent secondary pandemic of human or animal origin — something that must become a part of strategic planning in the future.

In the October 2020 issue of Frontiers of Veterinary Science, the paper Emerging Zoonotic Diseases: Should We Rethink the Animal Human Interface suggests due to the human-related nature of zoonotic disease, disease control strategies must be considered at a global level. That means including disease surveillance, animal welfare, population growth, trade, travel and the effect of livestock rearing. Without substantial change, humanity it seems is headed toward an irreversible global crisis.

Dr. Ron Clarke prepares this column on behalf of the Western Canadian Association of Bovine Practitioners. Suggestions for future articles can be sent to Canadian Cattlemen ([email protected]) or WCABP ([email protected]).