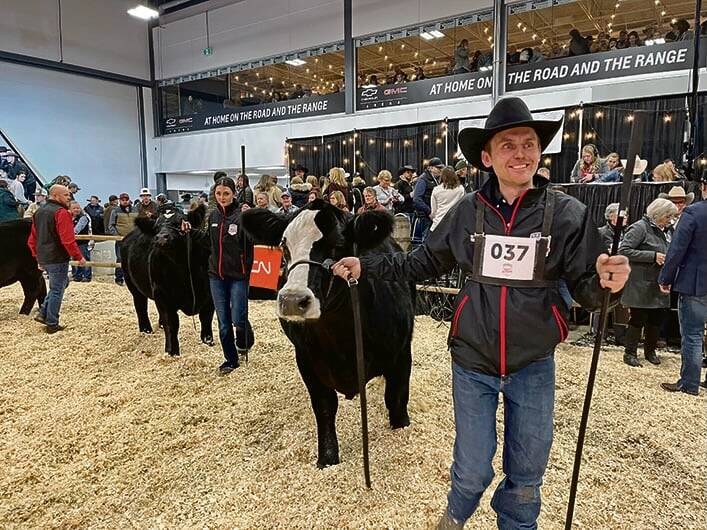

If anyone had predicted 20 years ago that Shane Gibson would someday run cattle as part of his farm operation, he would have said, “wrong.” As circumstances had it, he took over his grandpa’s herd when he was 15 and one thing led to another. Today, his time is split about 50-50 between his 300-head cow herd and 4,000 acres of cropland near the home place east of Carstairs, Alta.

He has learned from other producers and tried various new strategies through the years and feels he has finally hit on the right combination of genetics, feed and health for his operation.

Read Also

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

“When we were building the herd, I realized that I needed to make things easier and more organized,” Gibson says. “Once I was set up, then the numbers didn’t matter, that is, I wasn’t creating more work by adding more cattle. The time spent is the same because everything is more efficient.”

Some of the major changes in recent years have included revamping the cattle yard with larger pens, eliminating small pasture parcels, implementing one feeding system across the board, banking at least a half-year feed supply, and building a second calving barn to accommodate the move from spring calving to winter calving.

Part of the reason for moving calving from the traditional time slot in March and April was that it often dragged into May, interfering with seeding operations that can begin in April some years. The deciding factor, though, was the late-spring storms that can take a high toll on newborn calves.

Gibson first tried a January start to calving, but found there just weren’t enough sunlight hours to warm the calves during the day, which he feels makes a big difference in getting them off to a good start after they come out of the calving barn. The increase in weaning weights wasn’t enough to justify the expense put into the extra feed the cows required.

He nudged the start to February 1 and again one last time to the middle of February. Calving season officially gets underway about a week before then when the cows and heifers are moved into the large pens back of the calving barn.

The calving barn was designed with cow comfort in mind. It has ample 16-foot square pens and a sand floor. It’s not insulated, but the temperature is regulated with a thermostat-controlled infrared heater hung from the ceiling down the centre of the barn that cuts out when the temperature inside the barn hits -5 C. Maintaining the sub-zero temperature discourages the growth of pathogens and eases the adjustment to the outdoor temperature for the calves.

“There’s no question when you are calving in February, you have to be able to get those calves in out of the wind and paired up,” Gibson says. On days when it is warmer than -15 C with no windchill, he might move new pairs directly to one of the small outdoor pairs pens at the opposite end of the barn as long as they have paired up nicely. It’s really important when calving in corrals to remove the cows with the newborn calves right away, he adds. This eliminates confusion for the calves and the cows, preventing mixups of calving cows trying to steal newborns and newborn calves getting kicked when trying to nurse from the wrong mom.

After about a day together in the barn, the pair is ready to move outside to one of the small pens that holds about eight pairs. With 75 per cent of the cows calving in the first cycle, it’s not long before the next move to a large pen that accommodates approximately 50 pairs. Once that pen is full, the group of pairs is moved to a second pen a little farther out to make way to start a new group of 50 in the first pen. When it fills up again, the first group shuffles down to another pen, the second group follows into the middle pen, leaving the first pen open to start another group.

By March, the oldest group goes into one of the four nearby pastures of stockpiled native grass. These are wide-open pastures with portable windbreak fences, calf shelters and feed bunks that are moved around frequently. If, or more likely when, a late-spring storm hits, the calves on pasture are a month or two old, know where to go for shelter and come through it with flying colours. If worse comes to worst, the groups can be moved back into pens in the yard to wait out the storm.

Gibson does a bit of sorting into breeding groups as the pairs move through the post-calving pens, but for the most part, each group of 50 pairs stays together right through the summer on pasture. Gibson has found that keeping the age groups together works to his advantage should there be any disease issues.

He is relieved to say that he has made great strides in controlling scours, which has meant a significant savings on medications and labour and decreased the losses associated with reduced weaning weights. He credits this partly to the move to winter caving, but more so to the prescription mineral program his veterinarian developed about 10 years ago to address a scours problem at that time. The calves were getting sick because the ration wasn’t providing all of the minerals and vitamins the cows needed. The custom-made mineral mix targets the specific shortfalls in the forage produced on his land and must be fed as prescribed.

Gibson feeds a total mixed ration of silage, hay, straw and barley grain with the mineral and Rumensin added so that each cow gets a balance of everything she needs with every single bite. The ration is delivered daily to 30-foot steel feed bunks with enough head space for all of the cows to eat at the same time to make sure each gets her fair share. Feeding in bunks also eliminates the problem of feed wastage, which he found to be a major drawback with swath grazing in some years.

“If the cow has everything she needs, the calf will, too. It promotes good health for both the cow and the calf,” Gibson says. He also makes sure they stay in good physical condition for calving by placing the feed bunks in the field about half a mile from the water source.

He feels his high calving rate on the first cycle is a direct result of providing grain for additional energy, especially pre- and post-calving. “If you are going to calve in February, the cows need energy to keep warm and carry that big calf through January. I find it’s easier to keep them in good shape right from fall than to try to get it back later,” he explains.

In years when grain is expensive — meaning that it is tempting to sell the barley rather than feed it to the cows — he may cut back to feeding two or three pounds per cow per day. Then when a cold snap hits he can easily bump it up so they don’t lose condition. It’s not instant money in your pocket, but there is a pay off in terms of improved health and growth of the calves.

Gibson has been banking some feed — grain, silage, hay, straw, pasture — every year since the drought in the early 2000s with the goal of carrying over at least half of a winter’s supply each year. He admits it was tough to forego the cash injection during the transition years, but now it is just part of the routine. Even so, he still ponders the economic wisdom of carrying over feed inventory and has considered taking out forage insurance instead. However, when it comes right down to it, cows still need to eat. If he doesn’t have feed, chances are nobody in the area will have feed and that would mean trucking in a lot of expensive hay from another region. He still feels that banking feed is the best management tool to mitigate drought risk. At the time, it might seem expensive to carry the cost of the extra feed, but it could turn out to be the cheapest feed the next year, he adds.

He well-remembers his grandpa’s saying, “grass in the field is worth more than money in the bank.” It wasn’t unusual for ranchers to have two or three times as much land as they actually needed because during a drought, which was an ever-present threat in southwestern Saskatchewan where he ranched, the only option if you didn’t have feed was to sell the cattle.

“So, I learned that it’s okay if I don’t use a pasture or all of the feed,” Gibson says. “I like to manage my grass so there’s some left in the pasture. This way, I find I can start grazing earlier, usually go later in the fall, and leave a quarter or two for spring grazing, which eliminates sickness when I can move the pairs out to big spaces early.”

Since he and his dad, Gary, purchased seven quarters in the Hanna area for summer grazing, he has been able to give up some of the small pastures that each carried around 20 pairs for the summer. This has meant a savings on the labour and expense of maintaining all of the fences, and a dramatic time savings when it comes to checking cattle in the summer and gathering them in the fall.

Gibson adds that he doesn’t go it alone doing all of this. The farm has one year-round employee and he counts on his dad as well as seasonal and casual help during busy times such as winter calving.

Genetics is the final cornerstone of Gibson’s program. Over time the breeding herd has moved from predominantly Red Limousin to Black Limousin, to today’s Black Angus herd with a side of black baldies.

In 2001, he was able to purchase a herd of 30 registered Black Angus cows that turned out to be excellent cows. “They have left a huge mark on the herd and also allowed us to raise some of our own bulls as opposed to buying everything,” Gibson says. “Once we realized what we wanted, we found that the best way to get it was to breed for it. You need to be selective on both the bulls and the cows to achieve whatever your goals are.”

Generally, he weans and backgrounds the calves, packaging them up in lots of 40 to 50 calves that go directly to a feedlot. In 2010, he sold the steers directly off the cows at an average weight of 753 pounds.

Sometimes, and especially when calf prices are low, Gibson questions whether the additional work and expense associated with winter calving are worth it. He still has options to do things in more ways than one — calving in a stubble field if it is dry or swath grazing, for example — but if it turns 30 below for 30 days, they are set up to handle it. If it storms, the cattle are safe, people are safe and they are prepared to get through it.

“If I try not to manage things as much, I end up with more issues and the thing is, they are issues that I know I can fix,” he says. “Overall, right now, this is the program that works for me.”

Now, I find the cattle operation rewarding — not always the best economically, but in terms of its satisfaction and my pride in it. I think you have to figure out what works for your operation, what market you are aiming for, develop your program, then stick to it and make it as strong as you can.” C