Listening for blue jays call in early mornings in need of peanuts is a favourite pastime. I sit with Addie, our golden doodle, within a foot or two of what’s offered, coffee in hand and watch my friends wrap a beak around whole peanuts, then squirrel them away in adjacent spruce.

The routine stopped midsummer when the jays disappeared. On our walks, we found two decomposed jays lying in the green space behind our house. My initial thoughts: they died from highly pathogenic avian influenza, a viral disease that terrorized the Alberta poultry industry through the summer of 2022. Another possibility: late season West Nile virus, with its predilection for species of the Corvidae family. Corvids include crows, ravens, jays and magpies, among another 129 affected species. Reports also suggest West Nile virus has drastically reduced rough grouse populations.

Read Also

Effect of wildfire smoke on respiratory health in beef cattle

Of all domesticated species, cattle have the smallest relative lung capacity, making them particularly vulnerable to wildfire smoke.

West Nile virus jumped ship in the New York area around 1999, then spread northwest across North America as a passenger on migrating waterfowl. Crows and jays are known to get sick and die from the infection. Most birds survive as carriers. Since West Nile virus was discovered in the United States in 1999, the virus has been detected in over 300 species of dead birds. Mosquitoes spread West Nile virus as part of their blood meals.

People, when infected, often don’t develop signs or display only mild fevers and minor headaches. In a few cases, humans can develop life-threatening disease when infection invades the spinal cord or brain. In Western Canada, West Nile virus occurs in late summer and early fall, paralleling the hatch of several Culex species of mosquitoes. Horses are susceptible to West Nile virus. Mortality rates in infected horses range up to 25 per cent. Vaccination may be used to prevent infection in horses. Currently, there are three West Nile virus vaccines registered for use in Canada. Local veterinarians should be contacted for guidance on appropriate vaccination products and their use.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza, carried by migrating water birds, ravaged prairie poultry flocks through the spring and summer of 2022. Wild waterbirds, the natural reservoir of low-pathogenicity avian influenza viruses, are probably involved in long-distance spread of these viruses.

Friends visiting from home in Saskatchewan reported a massive die-off of snow geese and Canada geese during this year’s annual migration. Thousands of dead geese littered fields around the Watson Reservoir, a small PFRA dam near Avonlea that became a significant staging area for geese over the last thirty years. Highly pathogenic avian influenza turned out to be the killer, something not seen to this degree before. While chicken and turkey producers struggled to protect their flocks across the province, prevailing winds blew dead birds into lifeless mats along small bays and sloughs bordering the dam. An eerie quiet enveloped the place where our family enjoyed many fall hunts amongst the clatter of geese in search of food every morning and evening. Scavenging hawks and eagles also fell victim.

RELATED: How wild birds may spread avian influenza

Avian influenza in birds is caused by a Type A virus. Type A viruses occur naturally among wild aquatic birds worldwide and can infect domestic poultry and other bird and animal species. Wild aquatic birds include waterbirds — such as ducks, geese, swans, gulls and terns — as well as shorebirds such as storks, plovers and sandpipers. Wild aquatic birds, especially dabbling ducks, are considered reservoirs (hosts) for avian influenza A viruses. They often become infected, may not get sick, but still transmit the virus. Generally, avian influenza A viruses are very contagious among birds. Pathogenic viruses sicken and kill domestic bird species quickly. Mortality in chickens can be 90 to 100 per cent within 48 hours. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A virus infections in poultry can spill back into wild birds, spreading again when birds migrate.

This year’s situation is especially unusual for North America. The highly pathogenic avian influenza strain detected in wild birds happened only once before (between 2014 and 2016) when wild birds spread the disease from Eurasia to Alaska. That outbreak led to the deaths of more than 50 million domestic birds in the United States alone, costing US$3 billion. Then the virus “vanished,” says Andy Ramey, a wildlife geneticist at the U.S. Geological Survey Alaska Science Center in Anchorage.

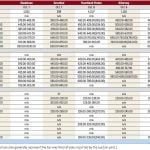

Canadian Food Inspection Agency data indicate 25 currently infected Alberta premises, and 96 country-wide, as of November 1. Over 3.2 million poultry have been infected in Canada. As of November 1, the U.S. dealt with 47.9 million infected poultry and 3,124 infected wild birds, the Center for Disease Control reports. As well, Canada imposed a ban on live birds, products and byproducts from the U.S. Before April 2022, Saskatchewan had remained free of avian flu for 15 years.

Chronic wasting disease is a degenerative and ultimately fatal disease of cervids (primarily deer and elk). It has affected wild populations of farmed cervids for several decades. Chronic wasting disease purges local cervid populations and remains a significant threat to deer populations in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Darrell Crabbe, executive director of the Saskatchewan Wildlife Federation, said the prevalence of the disease in some areas is “disturbing.”

In areas of North America, when chronic wasting disease prevalence reaches 30 per cent, populations of mule and whitetail deer decline. In the Saskatchewan River Valley, chronic wasting disease-positive deer (males) exceed 80 per cent. Chronic wasting disease has now been found in 59 of the province’s 83 wildlife management zones. The disease is considered endemic across southern Saskatchewan and south of the boreal forest. “These are among the highest rates reported globally,” states the Ministry of Environment.

The world is starting to realize that wildlife is not merely a source of personal pleasure. We are beginning to understand that the health of our wildlife is an indication of the health of the environment on which we depend. Healthy wildlife populations and habitats are important to our social and economic well-being, states the Canadian Wildlife Federation.

Understanding and accepting the challenge is critically important.

— Dr. Ron Clarke prepares this column on behalf of the Western Canadian Association of Bovine Practitioners. Suggestions for future articles can be sent to Canadian Cattlemen or the WCABP.