It is spring and the time when all Canadian farmers think of green grass, planting, awakening forests, early rains and trickling rebirth. This is our land and our livelihood and no one understands it better.

Our soil, so firmly attached to our working boots, is the foundation of our existence and the reason for the health and the wealth of our nation. Although fossil fuels are surely needed to farm today, it is food that got us to this point and renewable fuels such as trees that allowed civilizations to grow.

Read Also

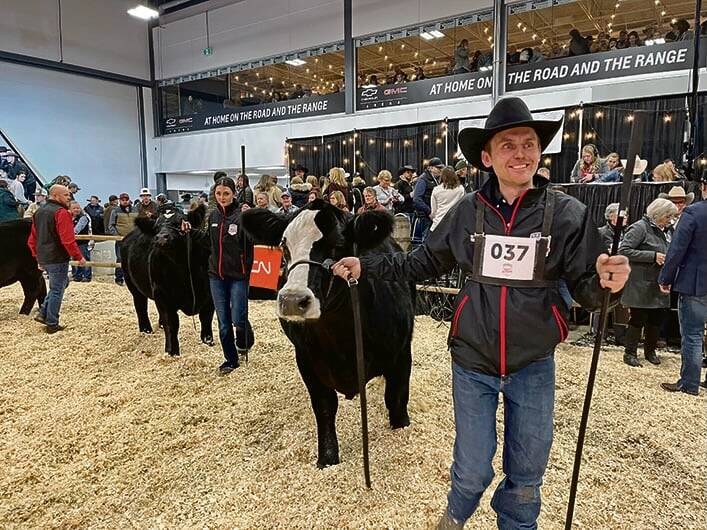

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

This is also a vulnerable world. Not from the sense that we are destroying it, but because it is so misunderstood and underappreciated. Only a few Canadians understand what a farm is or does. Most think there really is a climate change disaster (although the average temperature is actually cooling) and farming, particularly beef production, is responsible for most GHG emissions. (All of agriculture, forestry and waste is nine per cent of GHG). Farming is not responsible for the end of the earth as some would have us believe. Rather, we are the regenerators of life.

Let us be clear in our arguments. No one exists without healthy soil and healthy soil is dependent on carbon dioxide (CO2). CO2 is a renewable source of carbon and with sunlight is synthesized as sugar in plants. This feeds the plants and wards off pests and as the plant matures, the sugars go back down into the soil, feeding the microbes and the process is repeated in a biological process. Micro-organisms feed on the organic matter producing nutrients and those nutrients are taken up by the plant. When there is an imbalance, such as a shortage of CO2, the soil is bound and can’t take on extra responsibility. For example, if CO2 is not in abundance then nitrogen cannot be metabolized.

For the sake of agriculture I seriously question the science or sense behind a carbon tax. CO2 has never been scientifically linked to long-term global warming or extreme weather. The higher the concentration of CO2 the greater the production of plant life on earth — that is why many food producers, especially green houses, capture it and pump it directly back into the soil for plant growth. Is the desertification of areas due in part to a reduction in CO2 rather than an increase in it?

- More ‘Straight from the hip’ with Brenda Schoepp: What does it take for farmers to earn public trust?

When it comes to carbon tax, tax payers have become victims of a money grab with propaganda being masked as science, with a movement based on fictional fear and the complete lack of understanding of the importance of CO2 to life. In Alberta, for example, individual households will be taxed from $300 and up depending on energy usage for what is really a necessity — it is cold in winter. All buildings and houses are estimated to contribute eight per cent to GHG, so the logic that agriculture, forestry and families should foot the bill for the other 84 per cent is absurd. Real carcinogens released into the air will not be taxed and foreign-owned multinationals will be heavily subsidized to adjust. Governments fail to understand basic science. Carbon tax of the masses is not an environmental solution.

Forests or planted tree stands, grasslands and natural areas and forages are profound sequesters of carbon and they can handle massive change. They are long-term respirators that continuously recycle the CO2 into nutrients for the soil. The importance of these areas cannot be underestimated and ignoring their function or failing to value them is like choosing to live with one lung. Farmers then are the stewards of our greatest resource.

So why is research within ag being compromised? A case in point is the reduction of one half of the biotechnology research team at BASF. Chopping 350 out of a 700-person research team is pretty dramatic, especially when you are in the seed bed with Monsanto that has a strong desire to capture the pesticide arm of BASF. Why stop plant research now when we have never been under more pressure to secure the public trust in terms of handling a critical natural resource? If Monsanto wants farmers to have a one-stop shop to buy all their crop inputs and that stop is at Monsanto, we have a problem and that problem is about the perception of all of agriculture.

Massive intensive farms are critical in terms of meeting current and global food needs. Yes, they use more fossil fuel but they still sequester carbon and their value is in producing enough food per hectare/acre/metre that we can start to set aside an increasing amount of natural spaces. Great producers, they remain vulnerable to a loss of freedom of choice and increasing input costs along with poor public perception. It is this lack of appreciation that overlaps all farms, including those on rangelands and with extensive forage production.

Forage production can offset some negativity as we relate the importance of farming to press, policy-makers and our consuming public. Forage requires fewer inputs, less fossil fuel and is regenerative in nature. There is an interrelationship as legumes will develop a mycorrhizal association with grasses, fixing nitrogen in a swap for phosphate. There is also a relationship with wildlife and cattle that contributes to the entire food and nutrient cycle. Forage is the base for feed, bedding, fertilizer and is a carbon sink that builds the soil — the beginning and the end of the cycle.

The last thing we would call ourselves in this business is vulnerable — but we truly are until we can sell our value to all stakeholders from both an environmental and ecological standpoint.