When Theresa Zuk, a rancher based out of Arborg, Man., heard about the first Colorado low that swept through the province in the middle of April at the start of their calving season, she was nervous but knew they could handle it. The storm brought 29 centimetres of snow to Winnipeg, strong winds, and freezing temperatures. Once it passed, Zuk breathed a sigh of relief.

Then another Colorado low was announced in late April, this one bringing both rain and snow.

Read Also

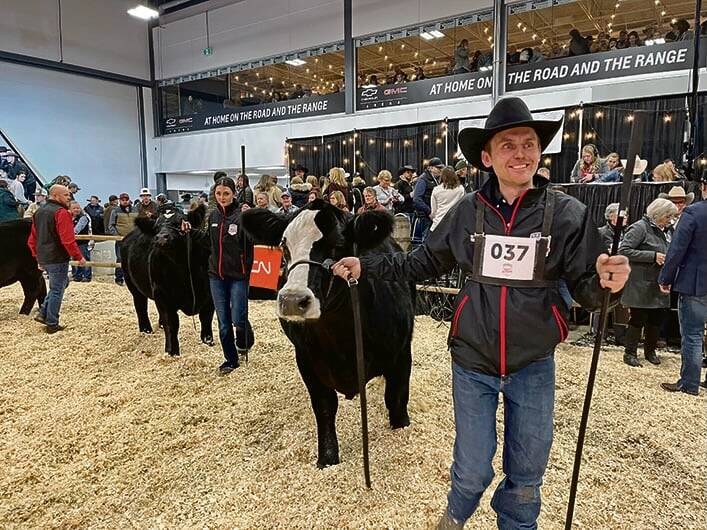

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

Then, another in early May, drenching the province in rain and causing many communities in southern Man., such as Arborg, to sandbag houses as the threat of floods loomed.

“I cried, I won’t lie,” Zuk says about the news of the third Colorado low. “Our third one was all rain and sleet. There wasn’t much snow, but it was the cold temperature and it’s just the wind. The wind is so miserable. It chills us, never mind these little babies being born and trying to get their feet up and trying to get them to suck.”

For Zuk and her family, who run their ranch Bar Z Ranch alongside Bar Z Beef, the continued storms strained their operation. As spring calvers, they don’t have the infrastructure to calve in the snow, or deep rain. Zuk says this has been the toughest calving year for their ranch to date.

“We have had some losses. We take losses very personally…come fall when we do round up, there’s just going to be significantly less.”

Tyler Fulton, the president of the Manitoba Beef Producers, says the same struggles are echoed in feedback from producers across the province.

“Some of the kinds of comments that I’ve heard is that it’s been taxing on their physical and mental health, just with the length with which we’ve been dealing with these really bad conditions,” Fulton says.

As a result, Fulton suspects the weather in Manitoba will have a critical impact on cattle herds this year — and going forward.

“Well, for some guys, we are talking about a very significant portion of their calf crop. I’ve heard about guys losing as much as a third,” he says. “So you can imagine we already are in a bit of a tight profit situation given the high cost of feed and we really haven’t seen any market change in cattle markets…now going forward, they won’t have the revenue in the fall. Now, on a short-term basis, they would likely be selling some of those cows. But from a long-term perspective, we’re talking about a huge blow to their farm’s and ranch’s viability going forward.”

For Zuk, there aren’t many changes they can make to their operation despite the struggle the Colorado lows have caused. Pushing calving later would interfere with haying and moves to June pastures. For them, the only other option would be to begin calving in February or March, but growing up calving in the late winter, Zuk says it’s not something they ever wanted to do.

“I think what we did was the best we could,” she says. “We’ll do anything we have to, to save a calf. And with what we had, I think we made good decisions. But to do anything different, we’re certainly not bumping it up.”

Fulton says he expects the storms to affect how producers manage their cattle going forward, but it will depend on each farm’s situation.

“It might motivate them to push their calving season back. It may also motivate them to change their planned carryover inventory of ingredients of feed and straw so that they can be more prepared for a late spring storm that ends up really taxing supplies. And I guess it may, it may influence some people to move the opposite direction where they might build some infrastructure, some calving barns or something and move it earlier in the season.”

The government of Manitoba is offering disaster financial assistance for the damage done by the Colorado lows — including for producers who have lost cattle due to the extreme weather.

“We need a shift in the weather so that these storms are routed further west, where they really need it, as opposed to the eastern Prairies where we continue to deal with some very poor conditions,” Fulton says.