You have to give the National Institute for Animal Agriculture (NIAA) some credit for the nerve to tackle one of the big dogs that has taken a huge bite out of the livestock industry for several decades now.

In a white paper released in May, The Precautionary Principle and Animal Agriculture, this non-profit association takes direct aim at one of the biggest drags on modern day agriculture.

I can’t say for sure why this topic caught my interest. Perhaps it was McDonald’s decision to turn to Canada as the testing ground for their certified sustainable beef program, or maybe I was looking for something to take my mind off the continuing war of words in a Washington court over the legal legitimacy of the U.S. country-of-origin labelling. Whatever it was I’m glad I picked up their report. This is one of those topics we can’t help returning to over and over again.

Read Also

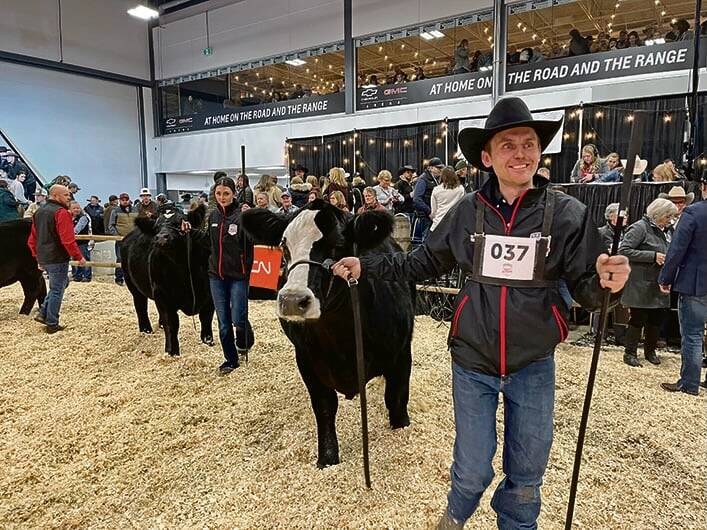

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

- More Canadian Cattlemen: Canada to produce world’s first McSustainable beef

It seems like the precautionary principle has been the rallying cry for environmental and other activist groups since the early ’80s when it was used to stir up public opinion in Europe against the use of hormones in beef.

Even when it is not officially adopted as policy by governments it still worms its way into political debates and regulations much as it did in the 1980s in Europe.

Better safe than sorry sounds a sane enough idea, but not without a clear definition of what is safe. Without that it is just a coward’s means to do nothing.

At its worst the precautionary principle stifles innovation. And that could be a costly mistake today when the world desperately needs new technology to grow enough food for an expanding global population.

“The precautionary principle could be used to prevent any new technology or product from being utilized if a person perceives that it might cause harm — and this belief takes hold without any consideration being given to the risks associated with the technology or product not being adopted,” says Dr. Mark Walton with Recombinetics, a Minnesota firm that has developed a gene editing technology for animal breeding, and one of the sources of the NIAA white paper.

“When selectively applied to politically disfavoured technologies and conduct, the precautionary principle is a barrier to technological development and economic growth,” he adds.

A now famous case in point is the cautionary tale of the AquAdvantage salmon.

It is a genetically modified variety of Atlantic salmon that has a single gene from a Chinook salmon spliced into its genome. This amounts to a change of 0.0001 per cent of the salmon’s DNA but with it AquAdvantage salmon reach 100 grams in 138 fewer days, are ready to market in half the time, consume 20 per cent less feed and have a five per cent better nitrogen retention than regular Atlantic salmon

No one is saying that this type of innovation shouldn’t be thoroughly examined and tested before it is approved to go into the North American food supply but this genetically enhanced fish has been under review by the U.S. government for 19 years. In 2010 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration finally deemed it as safe as any other Atlantic salmon to consume and no risk to the environment since it is grown in a contained environment. Yet it is still not approved, apparently held hostage by the precautionary principle.

Alaskan fisheries, activist lawyers, organic growers, non-profit voluntary citizen groups and the states of California, Oregon and Washington oppose it. Supporting the new strain are agricultural production states, production associations like NIAA, academics, animal health companies, and scientific associations. It is a familiar story and so far those on the precautionary side of these arguments seem to be winning, at least when it concerns enhanced animals.

NIAA says the company that developed AquAdvantage salmon has already invested more than $70 million in the project and has been close to bankruptcy four times. This is hardly an inducement to other innovators to try their hand at this technology.

NIAA’s solution is to attempt to set the bar for evaluating new livestock technology based on its sustainability rather than the precautionary principle.

In that vein NIAA is heartened by the efforts of McDonald’s, Walmart, Cargill, JBS, Tyson and groups like the World Wildlife Fund to create a global criteria to define sustainable beef.

That will eventually provide key production and environmental performance indicators that an industry can adopt. Perhaps this is one way to regain the trust of the consuming public sufficiently to do away with the fear-first precautionary principle once and for all.