The international body overseeing countries’ animal disease control measures has assigned Canada the lowest level of risk for bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) — a move which stands to help clear away lingering trade barriers against Canadian beef.

The World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) on Thursday announced it has delivered “negligible risk” status for BSE to both Canada and Ireland.

Canada, which has had “controlled risk” status for BSE since 2007, had applied to the OIE last July for the upgrade.

The OIE’s Scientific Commission for Animal Diseases in March this year ruled Canada fulfilled the requirements for negligible risk, and the World Assembly of OIE Delegates announced its vote of approval Thursday.

Read Also

U.S. livestock: Feeder cattle hit contract highs on tight supply

Chicago | Reuters – All Chicago Mercantile Exchange feeder cattle futures and most live cattle futures hit contract highs on…

Thursday’s decision marks “a historic closing of the BSE era for Canada which brought unprecedented hardship to our industry in the early 2000s,” Canadian Cattlemen’s Association (CCA) president Bob Lowe said in a release.

Many countries halted and/or restricted their imports of Canadian beef after Canada’s first case of BSE in domestic cattle was discovered in May 2003 — a “significant impact,” the CCA noted, as about half of Canada’s beef production goes to exports.

“Although difficult to fully quantify the direct economic impacts of BSE, between just 2003 and 2006, losses were estimated to be between $4.9 (billion and) $5.5 billion,” the CCA said. Since then, the beef sector has faced “opportunity costs of continued limited market access and additional processing costs.”

Between 2006 and 2011, the CCA said, 26,000 beef producers left the industry and over 2.22 million acres of pasture were converted to other uses.

The change in status from controlled-risk to negligible-risk “will help facilitate expanded access to foreign markets for various beef products currently limited by BSE era restrictions,” the association said.

Specifically, it “enhances (Canada’s) negotiation position in efforts to gain access to additional export markets for Canadian cattle, beef and beef products among countries that require products to originate from countries with negligible BSE risk status,” the federal government said Thursday in a separate release, noting it will inform those countries of the upgrade.

As of mid-March, remaining BSE-related export restrictions in some countries include a few all-out bans on Canadian beef — such as in Australia, Brazil, Malaysia, Bolivia and Uruguay.

Others, meanwhile, maintain import bans on Canada’s bone-in beef, offal and/or beef from animals over 30 months of age (OTMs), which are believed to be the highest-risk age group for development of BSE.

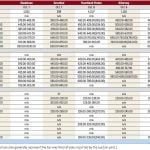

China, Russia and Peru, for examples, still accept Canadian bone-in beef only from cattle under 30 months (UTMs) and boneless beef from OTMs. Others such as South Korea, Ukraine, Saudi Arabia and Egypt accept Canadian beef but only from UTMs. Indonesia accepts Canadian boneless beef from both UTMs and OTMs.

‘Continued observance’

Federal Agriculture Minister Marie-Claude Bibeau on Thursday hailed the decision as “confirm(ing) that Canada’s beef production system is sound, safe and respected.”

The upgrade puts Canada on the same BSE risk level as many major beef-producing and -exporting nations including Australia, Argentina, Brazil, India, New Zealand, Mexico and, since 2013, the United States.

For negligible-risk status, a country must show its last case of “classical” BSE was born more than 11 years ago and effective control measures and surveillance systems are in place. Canada’s last BSE case, discovered in 2015, was in a cow born in 2009.

BSE in infected cattle concentrates in nervous system tissues classified as specified risk materials (SRMs), which are removed from all Canadian cattle slaughtered for human consumption. SRMs include the skull, brain, eyes, tonsils, spinal cord and nerve ganglia attached to the brain and spinal cord, plus the distal ileum portion of the small intestine.

To limit the disease’s spread among cattle, the federal government banned most proteins, including SRMs, from cattle feed in 1997, and since 2007 has banned SRMs from all feeds, pet foods and fertilizers.

The OIE requires negligible-risk-level countries to show evidence of an “effective” ban on ruminant-to-ruminant feeding for at least eight years and “negligible risk with regard to the BSE agent for at least seven years.”

As with controlled-risk countries, negligible-risk countries must also show “intensive” active surveillance for BSE over at least a seven-year period, and maintained over time, the OIE says.

BSE risk status, according to the OIE, only applies in relation to “classical” BSE, which is transmitted through infected feed sources, rather than “atypical” BSE, forms of which are believed to occur spontaneously in cattle populations at a very low rate. All but one of the cases seen in the U.S., for example, were deemed to be “atypical” BSE.

Maintaining OIE status for BSE “is dependent on the continued observance of OIE standards,” the federal government cautioned Thursday. “Failure to comply provides ground for the OIE to revoke the given status.”

‘Great day’

For its part, the CCA said Thursday it will now focus on getting remaining BSE-era market access restrictions removed, and on the “alignment of packing house requirements with international recommendations.”

“We thank everyone involved in helping us attain this status including the government of Canada, veterinarians across Canada and Canadian farmers and ranchers,” Lowe said. “We also thank Canadian consumers who supported Canada’s beef industry during the hardest times of BSE when Canadian beef couldn’t be exported.”

“This is a great day for beef producers across the country, many of whom remember the devastation caused by BSE when it first emerged in Canada over 15 years ago,” federal Trade Minister Mary Ng said Thursday. “With this recognition, Canada is positioned to negotiate greater access to international export markets for our top-quality beef products.”

Most of Canada’s major beef export markets have already approved all Canadian beef based on their recognition of controlled-risk status, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency noted Thursday.

Those include the U.S., which took in $2.5 billion worth of Canadian beef in 2020, along with Japan ($305 million), Hong Kong ($109 million), Mexico ($106 million), Vietnam ($41 million), the Philippines ($5.1 million) and the United Arab Emirates ($3.8 million).

Earlier this month, Canada reached an agreement granting beef export access to Oman. Full market access for Canadian beef was also restored this month in Kuwait following a similar agreement reached in mid-March, ending a BSE-related ban in that country.

Guatemala last month also confirmed approval for all Canadian beef, where previously its Canadian imports were limited to boneless UTM beef.

“On the negative side of the market access balance sheet, Qatar has reduced Canada’s previous full beef access to boneless UTM beef only,” the CCA noted in a statement last month.

Canada between 2003 and 2015 confirmed 19 cases of BSE in domestic cattle. A progressive, fatal disease of the nervous system in cattle, crudely called “mad cow disease,” BSE is in the family of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) such as scrapie in sheep, chronic wasting disease in deer and elk, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in people.

No treatment or vaccine against BSE is yet available, and no method yet exists to confirm the BSE agent’s presence in live animals.

From a public health perspective, the deaths of about 230 people worldwide from a variant form of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) are believed to be connected to consumption of contaminated beef from BSE-infected cattle.

According to Health Canada, no cases of vCJD have ever been linked to eating Canadian beef and BSE in Canada poses an “extremely low” risk to human health.

Among other decisions announced Thursday, OIE delegates also voted to deem Italy and Paraguay free of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP), three zones of Brazil free of foot and mouth disease (FMD), and two zones of Russia and one zone of Colombia FMD-free where vaccination is practised. — Glacier FarmMedia Network