Two simple observations at birth can tell you whether a newborn calf has the vigour to quickly suckle enough colostrum to achieve the protection of passive immunity.

“Measuring calving ease and suckle reflex is a quick and easy method to identify beef calves that are unlikely to consume colostrum by four hours after birth,” says Dr. Elizabeth Homerosky. She combined the two parameters into a Beef Calf Vigour Assessment to complete her master’s thesis on this topic at the University of Calgary’s veterinary medicine faculty and recently joined Veterinary Agri-Health Services at Airdrie, Alta., as an associate veterinarian.

Knowing that passive immunity is critical for the pre-weaning health and survival of beef calves, the objective of her research was to develop a user-friendly method of assessing calf vigour to identify calves likely to need assistance getting that first feeding of colostrum within four hours of birth. She followed through by evaluating how each calf’s vigour assessment related to its actual level of passive immunity, pre-weaning health and performance.

Read Also

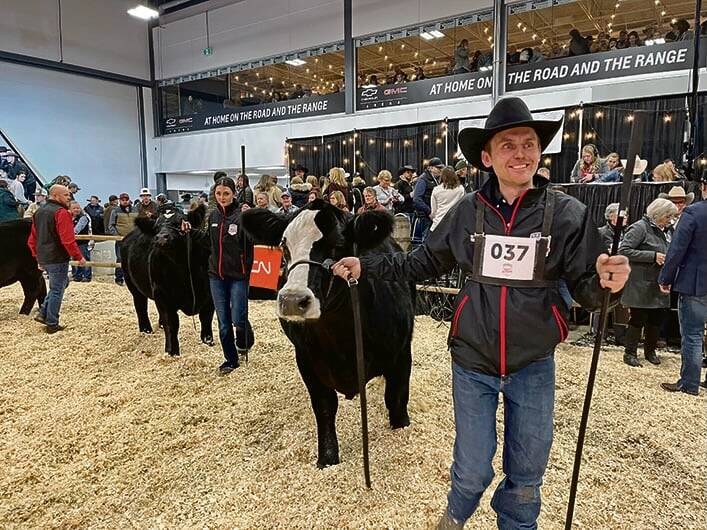

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

Homerosky recorded observations for 22 unassisted calvings, 41 easy-pull calvings, and 14 hard-pull calvings at a large cow-calf operation in southern Alberta. She examined each calf 10 minutes after birth, noting details such as meconium staining, heart and respiratory rates, suckle reflex and ambient temperature to determine which of those would best predict a calf’s ability to suckle on its own within four hours. Blood samples were drawn to test for pH and L-lactate among other parameters. All calves failing to consume colostrum on their own within four hours of birth were assisted by six hours, either by helping them latch onto the dam’s teat or feeding the dam’s colostrum by bottle or esophageal feeder.

Compared to unassisted calves, the easy pulls were 4.1 times less likely, and the hard pulls were 11.4 times less likely to suckle on their own within the critical four hours after birth.

The results were even more dramatic when the suckle reflex was weak. Those calves were 41.6 times less likely to consume colostrum by four hours after birth compared to calves with strong suckle reflexes.

“Combining measurements for calving ease with suckling reflex helps increase prediction accuracy,” Homerosky says. Calves born unassisted had a 14 per cent chance of failing to consume colostrum by four hours after birth. If the suckle reflex was strong, the risk of failure dropped to eight per cent; however, if the suckle reflex was weak, the risk skyrocketed to 78 per cent (see below).

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the hard-pull calves started life with a 64 per cent chance of failing to consume colostrum within four hours. With a strong suckle reflex, the probability of failure dropped to 49 per cent, but a weak suckle reflex almost certainly meant failure.

In the middle were the easy pulls. There was a 39 per cent chance they wouldn’t suckle on their own within four hours. A strong suckle reflex reduced the odds to 29 per cent, whereas the probability of failure jumped to 94 per cent if the suckle reflex was weak.

Measuring suckle reflex is easy to do, she explains. Approximately 10 minutes after birth, place two fingers along the full length of the top of the calf’s tongue, gently rub the roof of the calf’s mouth a couple of times and categorize the reflex as either weak or strong. Calves with poor jaw tone and/or poor suckling rhythm can be categorized as having a weak suckle reflex. Those with a strong suckle reflex will have good jaw tone and rhythm, and quickly latch on by curving their tongues around your fingers.

Blood test results offered insight as to the reason why some calves are born with a weak suckle reflex. Calves with low blood pH and high L-lactate concentration were more likely to have weak suckle reflexes and fail to consume colostrum on their own within four hours than those with normal blood parameters.

Homerosky says this is likely due to the fact that low blood pH and high L-lactate concentration are associated with low uptake of oxygen in the brain. This can negatively affect co-ordination and strength of muscle tone, but most calves are able to pull through the imbalance on their own within a matter of hours. Early intervention to hand feed colostrum can make all the difference, not only in mitigating the negative effects of low blood pH, but in the transfer of passive immunity to support pre-weaning health and performance.

Optimal passive immunity

Calves that consumed colostrum on their own within four hours after birth were 6.4 times more likely to acquire optimal passive immunity than those that failed.

Passive immunity is the transfer of gamma immunoglobulins (IgG) in the cow’s colostrum to the calf via absorption through the calf’s intestines. A newborn calf’s gut allows IgG to pass into the bloodstream for approximately 24 hours after birth. The most effective transfer is within the first four hours, after which the lining of the intestine gradually begins to close. A calf may fail to acquire adequate passive immunity if it doesn’t receive a sufficient amount of colostrum within that four-hour window or the concentration of IgG in the colostrum is inadequate.

A beef calf hand-fed its dam’s colostrum needs approximately one litre during the first feeding and a second litre no later than 12 hours after birth, Homerosky advises. If a commercial colostrum product is fed as the sole source of IgG, it’s important to select one labeled “replacer” with more than 100 grams IgG in the package. Products labeled “supplement” are intended to be given in addition to colostrum from the dam. Commercial colostrum products must be mixed and fed exactly as directed to ensure that the calf receives enough IgG. Dairy colostrum should not be fed to beef calves because of the exceptionally low concentration of IgG due to the high volume of colostrum produced by dairy cows and because of the risk of disease transmission.

If a calf’s suckle reflex is strong enough to take a bottle, it may be more beneficial than feeding with an esophageal feeder. The difference is that colostrum bypasses the rumen and goes directly into the abomasum when a calf is actively suckling, whereas esophageal feeders deposit colostrum directly into the rumen. IgG can be absorbed more quickly when deposited in the abomasum than when sitting in the rumen, she explains, adding that bottle feeding also reduces the risk of a calf developing pneumonia from inhaling colostrum.

Blood samples taken 24 hours after birth to measure the IgG concentration showed that all but eight of the 77 study calves had acquired optimal passive immunity.

A blood serum level greater than 24 grams of IgG per litre is recognized as the optimal level of passive immunity based on risk of sickness and death before weaning. Blood serum IgG concentration in the range of 16 to 24 g/l is considered adequate, 10 to 16g/l is considered marginal, and less than 10 g/l is the cutoff for diagnosing failure of passive immunity.

Although all study calves received colostrum within six hours of birth, those that consumed colostrum on their own within four hours of birth were 2.8 times less likely to be treated for illness before weaning and gained approximately 0.2 pounds per day more during the pre-weaning period than calves that failed.

Broader implications

Past research at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine estimated that one-third of beef calves in Western Canada fail to acquire an optimal level of passive immunity that is truly protective throughout the pre-weaning period.

Approximately seven per cent of beef calves born in Western Canada are assisted at birth. Although they are considered to be high-risk, they are the calves most likely to be closely observed and, therefore, to receive colostrum shortly after birth.

“It follows then, that the majority of calves failing to acquire optimal passive immunity must come from the unassisted population, which has generally been regarded as low risk,” Homerosky says.

Taking a moment to check the suckle reflex shortly after calving, assisted or not, is an effective way to identify calves at risk for passive-immunity failure. Stepping in sooner than later to assist those with weak suckle reflexes should improve calf survival and health, saving the expense of treating and losing sick calves.

Homerosky reminds producers that many factors, such as environmental conditions, the age and body condition of the dam, duration of labour, and mothering behaviour, affect newborn beef calf vigour and the time it will take them to consume colostrum.

“Unfortunately, closely monitoring labour and birth may not always be possible. The Beef Calf Vigour Assessment was designed to assess a newborn calf’s vigour status, regardless of the events that occurred before or during birth. Newborn beef calves that consume colostrum by four hours after birth should be considered vigorous by definition (strong, healthy and full of energy) because their actions are helping to promote good long-term health,” she says.

Homerosky’s hope is that the Beef Calf Vigour Assessment will help producers minimize the proportion of calves that fail to acquire an optimal level of passive immunity, thereby improving overall calf survival, health, performance and profitability.

Curious as to whether your calves are acquiring effective passive immunity? Ask your veterinarian to draw blood samples from a few calves 24 to 36 hours after birth to send to a laboratory to test for IgG levels.