Occasionally cattle suffer from kidney stones or bladder stones, just like humans. These are called urinary calculi, and are mineralized clumps in the urinary tract. In cattle, bladder stones are more common than kidney stones.

Small ones usually pass out with urine and are not a problem, but sometimes stones become caught and create a blockage. This happens more frequently in males and only rarely in females because females have a shorter, larger urethra. The urethra in the male makes a curve as it comes out to the prepuce, and stones may get caught in that bend. Blockages occur more commonly in steers than in bulls; the passage is slightly larger in the intact male than in the castrated animal. Stones can sometimes be a winter problem if cattle are not drinking enough, which can happen in cold weather.

Dr. Bart Lardner, research scientist at the Western Beef Development Center and adjunct professor in the department of animal and poultry science at the University of Saskatchewan says diet can be a major factor and is part of the challenge of prevention.

For that reason stones are more often an issue in a feedlot.

A growing calf in a backgrounding or feedlot setting will be exposed to a higher concentrate diet with more cereal grain, which may alter the calcium-phosphorus ratio. The feedlot diet may be higher in phosphorus than a pasture diet, and this could be an issue, he says.

“There may be stress of trucking, not drinking enough, stress of changing diets, and so on.”

Dr. Steve Hendrick of the Coaldale Veterinary Clinic in Alberta, however, says stones are less common today than in the past, partly because feedlot diets are more balanced now.

Water sources at a feedlot are usually adequate, as well, to ensure there is plenty of fresh water summer and winter.

Dehydration can lead to urinary stones, and could potentially occur at other times of year if cattle don’t have access to water, or the water source dries up in hot weather. It’s not just the quantity of water, but also the quality. Water high in sulfates or other minerals might contribute to stone formation.

Stones form in the bladder when minerals in the urine start clumping around some type of nidus. It could be cells inside the bladder that naturally slough off. Minerals start clustering around that material and form calculi. Small crystals generally pass easily.

Read Also

Body condition, nutrition and vaccination for brood cows

One of the remarkable events of the past century related to ranching has been the genetic evolution of brood cows….

“If water is restricted, however, urine is more concentrated, the animal won’t urinate as frequently and these calculi are not as readily flushed out, and grow larger,” Hendrick says. When that happens, the stones may get big enough to become stuck in the urethra.

“When cattle are on pasture, eating grass, the stones tend to be made up of silica from the ash content of the grass. It would partly depend on the type of pasture, whether native or tame, but we do see some high ash content even on some of our tame pastures. I’ve been surprised sometimes when doing feed analysis, looking at some of the pastures; it’s not uncommon to see levels as high as 10 to 12 per cent ash. Some plant species like kochia are even higher,” he says.

“These plants may not be what the animals are generally eating, but if the pasture gets dry or you get into drought conditions, having restricted access to water and eating different types of plants or plants that are more mature may make a difference. The ash content goes up as the plant matures. Dry matter and nutrient levels change.”

When urinary stones occur in pastured animals, Hendrick says they are commonly made up of silicates, but with certain plants there can be oxalates as well. “In the feedlot a high grain diet, with more phosphorus, can also lead to stone formation. With higher levels of phosphorus we need to provide more calcium to balance that diet,” he explains.

“If a stone becomes lodged in the urethra it blocks the passage of urine, creating pain and pressure. The signs would include going off feed, discomfort (kicking at the belly), dribbling small amounts of urine, or straining.

“We often see a pumping of the tail as the animal tries to pass urine, and it may look like he is constipated, trying to poop,” says Hendrick.

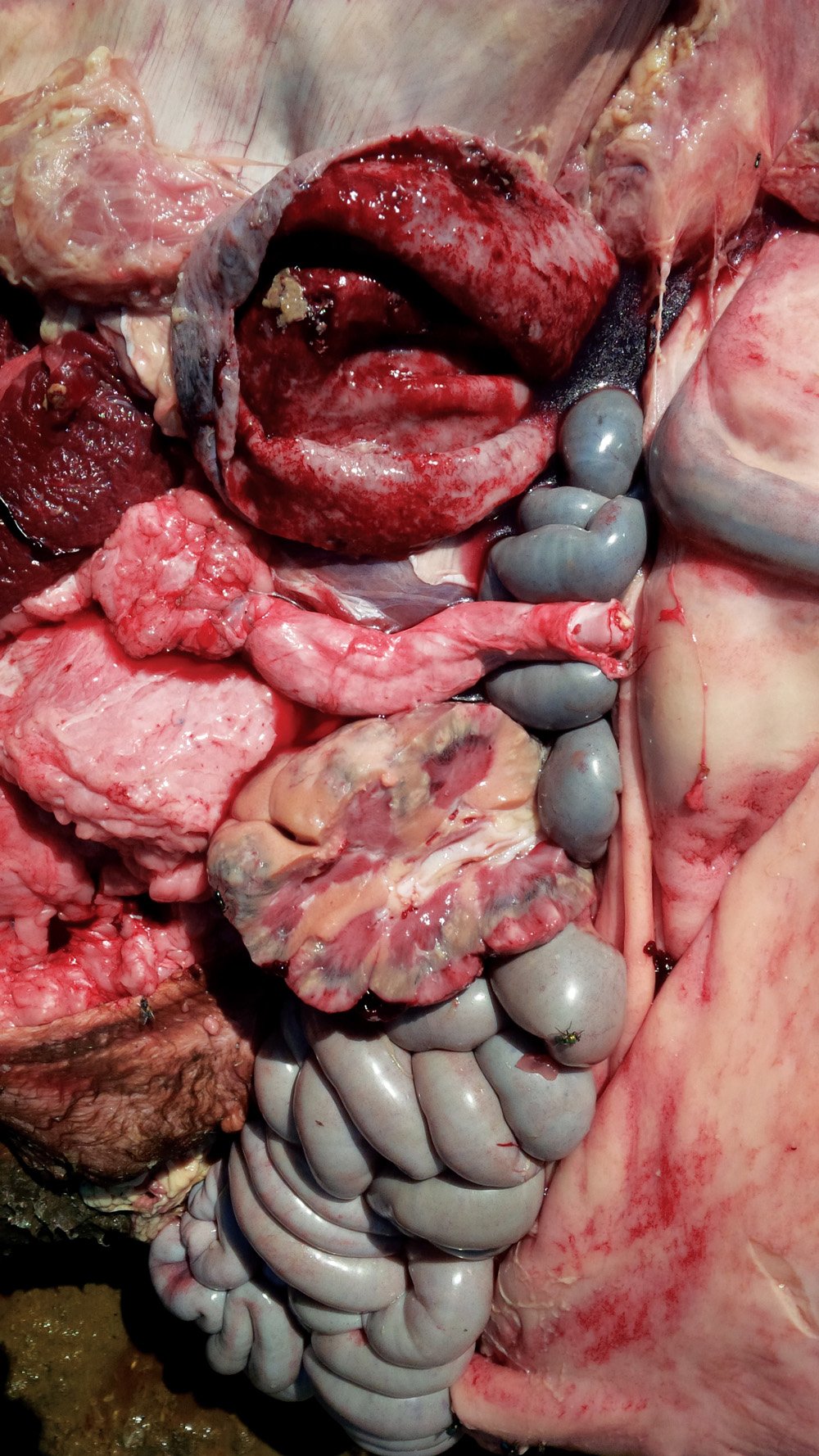

“There may be swelling between the hind legs, down along the sheath. This means that the urethra has ruptured and urine is seeping out into the surrounding tissues. Or it may be a ‘water belly’ where the bladder has burst. At that point the animal may initially be more comfortable (as the pressure has been relieved), but if it’s not dealt with fairly soon it becomes a problem having urine in the abdomen. It’s very irritating and also causes infection, which can be fatal.

“It’s not uncommon for urinary stones to lodge in the urethra. There are a couple of spots in steers or bulls where they might get stuck. One place is an S-shaped curve (the Sigmoid flexure) that tends to be a bottleneck. The other common spot for a stone to lodge is just after the urethra leaves the bladder, where it has to go around the pelvis. We call that part of the pelvis the ischium. As the urethra bends around the ischium, and goes down between the hind legs, this is a narrowed place where we may find stones lodged, as well,” says Hendrick.

If the producer recognizes signs soon enough, and enlists veterinary help for the animal, a blockage can be removed before the bladder or urethra ruptures.

“Some people talk about crushing the stones so the particles can pass on through, but some stones are very hard. It depends on the type of material they are made of,” says Hendrick.

“More commonly we do a surgery called urethrostomy which means carefully dissecting out the urethra and pulling it out the back end of the calf, so the urine exits the body beneath the rectum, like a female.” This surgery is often termed a high heifer.

Sometimes the bladder needs some time to recover after being stretched so much, due to the blockage and accumulation of urine. The veterinarian may put a catheter into the bladder and leave it there for a couple of days to help drain it. This gives the bladder time to rest and heal. Then when the catheter is removed the animal can urinate on its own.

This is not a long-term solution, however. “The surgical removal of a stone and rerouting the urethra is a salvage procedure, just to keep the animal alive and allow it to recover enough to be butchered,” says Hendrick.

If left, these animals rarely go on to finish at a typical weight.

“There is a tendency for some of these animals to re-block even after surgery, or have subsequent issues,” says Hendrick.

Urinary blockage tends to be more common in early-castrated steers than bulls, because the urethra may be smaller.

“That’s not a good reason to delay castration, however,” cautions Hendrick. “The incidence of stones is fairly rare, and we can manage those cases. It’s not worth the other risks and problems associated with delayed castration, which is much harder on the animal, with setback in growth,” says Hendrick.

Feed management, with diet and adequate clean water are the keys to prevention.