From a feed grain perspective, this fall and winter promise to be challenging for cattle feeders. At the time of writing, the 2021 western grain harvest was nearing completion. Traditional feed grain supplies (i.e. barley and feed wheat) will be tight. Furthermore, feed grain prices remain at peak levels and have shown no inclination to move without significant changes in supply. This situation has forced the feeding sector to look for alternative solutions for meeting the energy needs of finishing cattle.

Read Also

Picking the most efficient cows to rebuild your cow herd

A new cow ranking system to help beef farmers and ranchers pick the most efficient cows as they rebuild their herds.

For some, the alternative is imported U.S. corn or its counterpart from Central Canada. While feeding corn is not new to cattle feeders in Eastern Canada, it will be a new experience for many feeders in Western Canada. For those new to feeding corn, I would like to use this column to highlight both its benefits as well as its drawbacks when fed to finishing cattle.

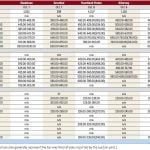

First let’s look at differences in nutrient content between corn, wheat and barley. The net energy for gain (NEg) content of dry rolled corn is listed in the latest edition of the Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle at 1.49 Mcal per kilogram (kg) of dry matter (DM) (NRCB, 2016). Wheat has a similar NEg (1.47 Mcal/kg) while barley is listed at 1.4 Mcal/kg, a value that is five to seven per cent lower than corn or wheat.

In contrast, wheat has the highest crude protein (CP) content at 14 per cent followed by barley at approximately 11 per cent and corn at nine per cent. The higher energy value for corn and wheat and the higher protein content of wheat usually dictates a premium relative to barley. Performance, however, does not always justify this premium, a situation I will discuss shortly.

The amount of supplemental protein required in a finishing diet will vary with the forage source as well as with the formulation target; however, it should be evident from the above discussion that the need for supplemental protein will be greatest for corn grain-based diets followed by barley and then wheat. Mineral content does not vary a great deal across the three cereal grains, with differences usually reflecting regional rather than plant species differences. You should be aware that all cereal grains are low in calcium, particularly for finishing cattle. It is for this reason that limestone is a significant component of most finishing supplements.

One of the greatest differences between these three cereal grains is in the need for and the response to processing. The barley kernel has both an outer hull and an inner seed coat that is very resistant to chewing by the animal and to fermentation by rumen bacteria. It is for this reason that barley is processed before feeding, typically by dry or temper rolling. While the wheat kernel does not have a hull, its seed coat is also resistant to chewing and bacterial fermentation and requires processing, typically by dry or temper rolling.

Corn is different in that its seed coat is penetrated by the animal’s chewing activity, allowing rumen bacteria access to the enclosed starch granules. Thus, cattle can be fed whole shelled corn with reasonable performance expectations. Dry rolling is also common practice with corn, although the improvement in performance relative to feeding whole is not as great as you would expect. In fact, if one looks at research trials evaluating the performance of cattle fed dry rolled corn to those fed dry rolled barley, more often than not the barley-fed cattle come out on top. This is likely due to reduced ruminal starch digestibility of dry rolled corn relative to that of barley.

More extensive processing of corn (i.e. steam flaking) improves ruminal starch digestibility and increases its NEg content to 1.67 Mcal/kg or a 12 per cent increase over dry rolled corn. Cattle performance, particularly feed efficiency, improves as a result. Recent research from the University of Saskatchewan shows that steam flaking barley may also improve feed efficiency relative to dry rolled barley. Unfortunately, few Canadian feedlots are set up with steam flaking technology and as such, most producers will continue to rely on dry or temper rolling as the methods of choice for processing these grains.

Another area to consider when feeding corn is the potential for rumen acidosis. Like barley and wheat, corn has a significant starch content and can lead to rumen acidosis if unadapted cattle are fed rations with too high a level of grain, too quickly. However, as alluded to above, the starch in the endosperm of the dry rolled corn kernel is fermented in the rumen relatively slowly, particularly compared to that of wheat or barley. While acidosis is a potential concern, proper feed processing (i.e. control of fines, targeted processing index) and ration management can minimize the incidence of this metabolic disease.

Finally, in light of the widespread nature of this year’s drought, you might question the feeding value of light test-weight corn. This has been the topic of several research trials over the years. The results show that performance of cattle fed corn with a test weight of 46 lbs. is not greatly different from that of cattle fed 56-lb. corn. Feeding corn with lighter test weights (i.e. <40 lbs.) can result in an increase in DM intake and consequently poorer feed efficiency.