As a veterinarian, I wondered for many years if animals and humans could function normally in an environment free of pathogens, free of stress and devoid of all things considered harmful. What might the balance be between not enough and too much? Are city kids raised in a semi-sterile milieu advantaged or disadvantaged compared to those of us raised around animals in contact with cow chips and guano every day?

What evolutionary role does hygiene play in kids who frolic in farmyard dirt versus those attending unsoiled daycares?

Read Also

Body condition, nutrition and vaccination for brood cows

One of the remarkable events of the past century related to ranching has been the genetic evolution of brood cows….

According to the hygiene hypothesis, the decreasing incidence of infections in western society and, more recently, in developing countries may be the source of increasing levels of autoimmune and allergic diseases. Lifestyle changes in industrialized countries led to a decrease in infectious burden, and resulted in the inadvertent escalation of allergic and autoimmune diseases, including Type 1 diabetes (T1D), multiple sclerosis (MS), atopic dermatitis, and Crohn’s disease.

Data demonstrates that people migrating from countries with a low-incidence of immune-based diseases to countries with a high incidence of immune disorders acquire new immune-based illnesses within the first generation following relocation.

D.P. Strachan, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine proposed the “hygiene hypothesis” in 1989. He observed an inverse correlation between hay fever in older siblings from British families reporting respiratory infections when young. The leading idea at the time: some infectious agents are able to protect against a large spectrum of immune-related disorders. Although the causal link between acquired immune disorders and the decline of infectious diseases remains in question, animal studies demonstrate quite clearly that the hygiene hypothesis does exist in nature.

Underlying mechanisms attributable to the hygiene hypothesis are multiple and very complex. They arise from changes in populations of microbes and parasites in both animals and humans — some concurrently; changes in lifestyle; and the constant, intricate regulation of the human immune system. Taken together, the bits and pieces we begin to understand about the hygiene hypothesis opens new therapeutic perspectives in preventing and treating autoimmune and allergic diseases.

Five decades ago, researchers first began to find evidence of an upside to parasitism. People in Nigeria had lower levels of arthritis and other immune-related diseases than people in Britain. Researchers suggested that chronic infection with intestinal worms and other parasites moderated the immune system in Nigerians, reducing the risk that the body’s own tissues would be attacked.

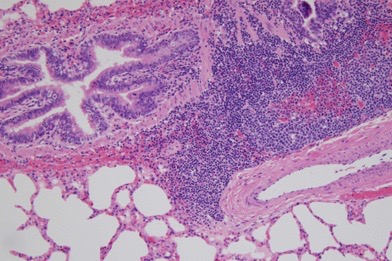

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis has doubled or tripled in industrialized countries during the past three decades, affecting 15 to 30 per cent of children and two to10 per cent of adults. In parallel, there is an increase in the prevalence of autoimmune diseases like T1D, which now occurs earlier in life than in the past, and is becoming a serious public health problem in some European countries. The incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn’s disease is also rising.

A number of experiments indicate that infectious agents can promote protection from allergic diseases. This has been demonstrated in experimental models of genetically modified mice highly susceptible to T1D. Treatment of mice with specific immune agonists completely prevented the progression of diabetes. Similar data has been observed in asthma models. The prevalence of atopic diseases in childhood (asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis) is reduced in families exposed to Hepatitis A virus.

Public health measures introduced to limit the spread of infectious disease after the industrial revolution in western countries predestined the rise of immune-based illnesses.

Proponents of the hygiene hypothesis contend measures like decontamination of the water supply, pasteurization and sterilization of milk and other food products, respect for cold chain procedures, vaccination against common childhood infections and the wide use of antibiotics had a role to play. It’s paradoxical that important public health initiatives that save millions from the ravages of serious disease every year opened the door for a plague of allergies and autoimmune issues.

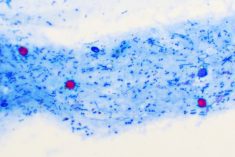

In countries where good health standards do not exist, there is an inverse relationship between the prevalence of soil-transmitted helminthes and the prevalence of allergic diseases.

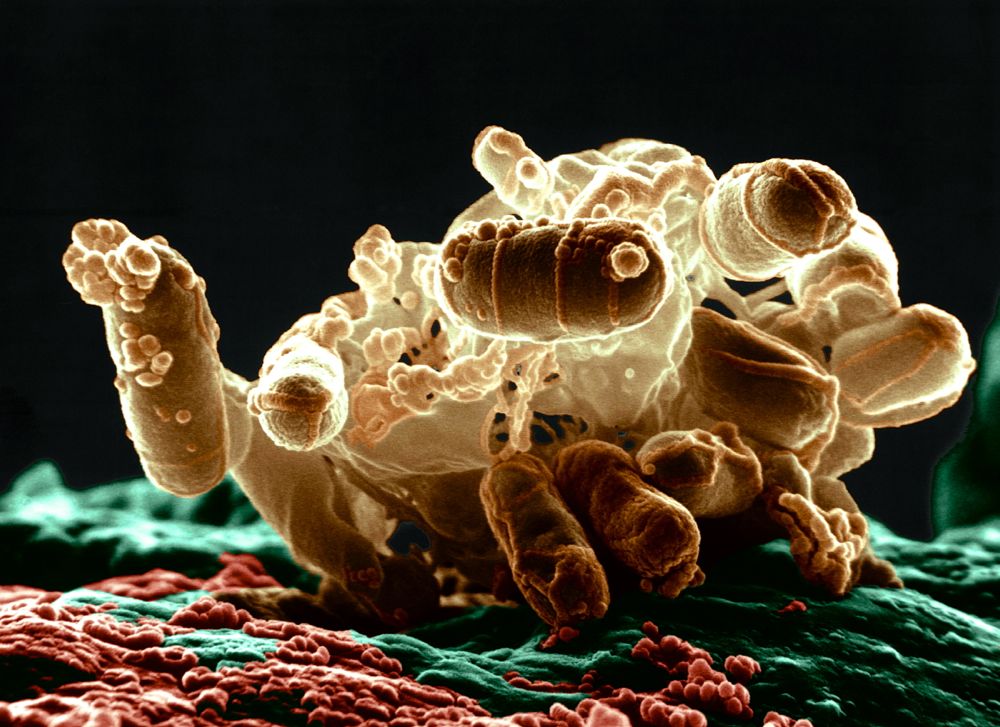

Conservation biologists contend that parasites of endangered hosts should be conserved as part of their host’s natural environment. Parasitic exposure might be crucial to the host’s development of a fully functional immune system and its survival.

“We’re trying to find elegant ways to spread the message that parasites are very important parts of ecosystems,” said Andres Gomez, an ecologist and veterinarian at Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History.

Not surprisingly, many people fail to share his view. According to Gomez, parasite conservation presents a critical conundrum: to conserve bloodsuckers and disease spreaders is to explicitly conserve death and sickness. In nature, this is a normal part of a functioning ecosystem, but for human society and health, the trade-offs don’t work.

The notion of a hygiene hypothesis opens new, interesting, therapeutic perspectives for the prevention of allergic and autoimmune diseases. Introducing infectious agents into children or adults at high risk of developing autoimmune diseases cannot be envisioned. However, some groups are using live swine parasites (T. suis) in the prevention of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), or living probiotic (Lactobacilli) in prevention of atopic dermatitis. The use of bacterial extracts has already shown to be efficacious in a number of experimental models for Type 1 diabetes.

Through millions of years of evolution our bodies maintained a tricky balance. We depended on a powerful immune system to fight deadly infections, yet selective enough to prevent the indiscriminate attack on beneficial bacteria, or tissue through relentless inflammation. The hygiene hypothesis, maintains our ancestors tolerated low levels of infection and depended on parasites to support development of the immune system. According to Gomez, “Our relationship with parasites is a complicated trade-off. If all parasites disappeared tomorrow, we’d have a teetering ecological house of cards ready to crumble.”

— Dr. Ron Clarke prepares this column on behalf of the Western Canadian Association of Bovine Practitioners. Suggestions for future articles can be sent via email to Canadian Cattlemen or to the WCABP.