A recent review of health records from 24 Alberta feedlots covering approximately 445,000 head revealed that lameness affected 6.1 per cent of the animals, but accounted for 28 per cent of all treated animals and 49 per cent of euthanized animals, while incurable respiratory disease accounted for 10 per cent.

The finding, which was part of a larger study in progress led by researchers from the Lethbridge Research Centre and University of Calgary Veterinary Medicine (UCVM), didn’t come as a surprise to veterinarians who work with feedlots because improved medicines for pneumonia in combination with treatment on arrival have substantially reduced the number of respiratory disease cases in fall-placed calves.

Read Also

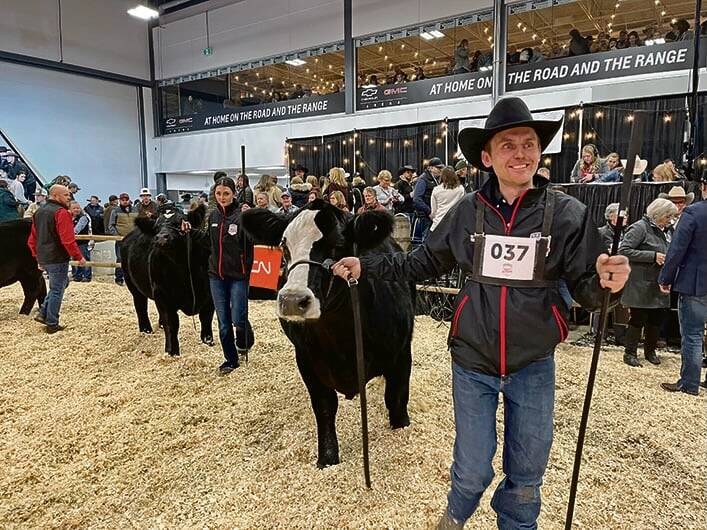

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

It’s easy to see that an animal is lame, but not always as easy to determine what’s causing the problem. Dr. Michael Jelinski of Veterinary Agri-Health Services, Airdrie, Alta., demonstrated this concept in a video quiz to lead off a lameness workshop held at the UCVM annual beef cattle conference this summer.

Narrowing it down to lameness most often seen in fall-placed calves in Western Canada, he says foot rot, mycoplasma arthritis, toe-tip necrosis and, in some feedlots, digital dermatitis are leading causes. Laminitis, injuries and potential ergot poisoning may also be problematic.

- More from the Canadian Cattlemen: The importance of field diagnosis

Foot rot and digital dermatitis

Classic signs are rapid swelling and redness in the soft tissue between the claws usually causing the claws to spread apart. The area feels warm and has a rotten odour if the infection is oozing out. Left unchecked, the swelling will spread up around the hairline at the top of the hoof and back into the dewclaw area up the fetlock.

Typically, the animal will be very lame and avoid putting weight on the affected hoof if at all possible.

“If foot rot is suspected and it doesn’t respond to an antibiotic appropriate for foot rot, then it’s probably not foot rot,” Jelinski says. Unfortunately there are plenty of alternatives causes for lameness.

Digital dermatitis (hairy heel warts) is a highly contagious skin infection that doesn’t respond to injectable antibiotics.The cause is still not clearly understood, but spirochete bacteria along with other bacteria and possibly a virus have been implicated.

Raised lesions appear between the claws and often on the bulbs of the hooves and around the dewclaws. Swelling isn’t common, however, the lesions may occur along with foot rot.

Historically, digital dermatitis has been an issue in dairy barns, but its prevalence has been increasing in Alberta feedlots in recent years.

-

Digital dermatitis

-

Digital dermatitis

The standard dairy treatment is to clean the foot and apply a topical antibiotic with a short-term wrap, Jelinski explains. This can be difficult to do in a feedlot. In outbreak situations, feedlots have used footbaths of copper sulphate or formalin with some success.

“Given the increasing prevalence of this disease and the difficulty managing it, it’s important for feedlots to be vigilant with lame cattle that are not responding to treatment for what may appear to be foot rot,” he advises.

Mycoplasma arthritis

Mycoplasma arthritis generally starts as a pneumonia. When animals are under stress with weakened immune systems, mycoplasma bacteria can invade the lungs and from there enter the bloodstream and settle into joints.

Any joint can be affected, but ankle, stifle, hock, and elbow infections are common.

Stifle joint infections caused by mycoplasma arthritis may be mistaken as foot rot, however, animals with a stifle problem will typically stand with the toe on the affected side just touching the ground and the foot won’t be swollen.

Mycoplasma pneumonia can respond to an appropriate antimicrobial given early, but joint infections are difficult to treat. You have to get enough antibiotic into the joint to be effective, especially when there is tissue damage from the infection. Some of these animals will come around with time, but it could be weeks or even months. About one to two per cent of animals in a feed yard will be affected with a joint infection due to mycoplasma and some will require euthanasia, but the numbers vary greatly by feedlot.

Toe-tip necrosis syndrome

One theory is that it sets into the hoof through a weakness at the tip of a claw thought to be caused by wear and tear on the hooves that happens along the way from the farm to the feedlot. Typically, it starts in one or more hind claws, but can affect front claws as well.

Jelinski says some feedlots see it more than others. The big risk factors seem to be transport time, animal temperament and floor conditions.

Although most feedlots are aware of the condition, it is often misdiagnosed as an injury due to trauma or handling because lameness may start to appear within a few days after arrival.

This is why treatment is often delayed. In the meantime, the infection may spread deeper into the claw tissues and bone where it becomes untreatable and ends up with the animal being euthanized. It’s often a surprise to see what’s going on in the hoof when the animal is necropsied, Jelinski adds. For more detail see our related story in this issue.

Sloughing hooves

Ergot toxicity has been more common in recent years with wet growing conditions more conducive to ergot bodies forming in cereal heads, says Jelinski. The severity of associated lameness problems tends to cluster by feedlot depending on where they source grain. Grain screenings in pelleted supplements are another source of ergot toxins.

Ergot toxicity may first show up as lameness in the feet. Over time a line of demarcation (splitting of the skin) may become evident between the dead and healthy tissue. Some hooves may be affected worse than others and in severe cases the entire foot or claw sloughs off.

“The degree of damage caused by ergot toxins depends on the amount of toxin consumed and animals may recover from low-level poisoning when contaminated grain is removed,” he says.

Prairie Diagnostic Services at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine in Saskatoon now has equipment in place to test feed for ergot toxins.

- From the Manitoba Co-operator: Frozen ears and feet – but not from the cold

Laminitis

In a healthy hoof, a layer of laminae cushioned between the hoof wall and the third bone (the bone coming down to the tip of the hoof) holds the bone parallel to the hoof wall. When laminae weaken or tear from the hoof wall, the third bone begins to rotate downward putting pressure on the sole.

Laminitis in feedlot cattle is associated with a rapid increase in highly digestible carbohydrates (grain) in the diet, which changes the acidity in the rumen and in turn kills off some types of digestive organisms that release toxins into the bloodstream as they die. The toxins cause swelling in blood vessels of the hooves leading to impaired circulation.

A hardship groove associated with an abrupt change in diet will become noticeable across the hooves as they grow out. Sole overgrowth, skinny claws (flipper feet) and other claw abnormalities may become apparent in time.

Once laminitis sets in there is no practical treatment, however, animals with mild cases may get along just fine on soft ground in well-bedded pens. Marketing affected animals in a timely manner is advisable.

Others

Bruises, sprains, torn ligaments, ruptured tendons and, the very odd time, fractures can happen during routine handling and in pens when animals jostle at the feed bunk.

Nerve and brain damage also cause peculiar behaviour and strange gaits which can be mistaken as lameness.

Spastic paresis is an example of a hereditable condition where sensors in the muscle bundles keep the leg muscle tight causing the hock to hyperextend with each step. A severe joint infection can trigger an acquired form.

Abscesses from needle injection sites too close to the spine have been known to create a “wobbler” when the infection pushes up into the spinal cord just behind the head.

“Lameness is, of course, an economic concern for feedlots because of the cost of medications and labour to care for the animals, but it’s equally an animal welfare concern because many lameness conditions are very painful and may become chronic,” Jelinski says. “Unfortunately, we can’t do much to manage the pain. Unless we know the condition has a chance of improving with appropriate treatment, it’s best to deal with it by early marketing or euthanasia.”