I once spent a summer working for canola breeders. Some used traditional selection, while others were experimenting with transgenics. One traditionalist was known to say “sticking a new gene into a plant and expecting it to grow better is like throwing a new gear into a watch and expecting it to keep better time. It’ll probably get worse.”

This article isn’t about canola or genetics, but it is about time and unintended consequences. Specifically, it’s about the timing of the breeding and calving seasons.

Read Also

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

Canada’s cow-calf sector has moved towards fewer, larger beef cow herds. Calving later, on pasture, has been a widely adopted strategy allowing producers to expand their cow herds without a proportional increase in equipment, labour and facilities. When John Basarab led Alberta’s Cow-Calf Audits in the late 1980s and late ’90s, breeding often started in May and calving in late February. In contrast, 70 per cent of the producers responding to the 2017 Western Canadian Cow-Calf Survey started breeding in June or July to calve in March or April.

Cheryl Waldner, Sarah Parker and John Campbell of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine established the Western Canadian Cow-Calf Surveillance Network (WCCCSN) under the 2013-18 Beef Science Cluster. They recently published a study that revealed potential tradeoffs between different breeding and calving seasons (Identifying performance benchmarks and determinants for reproductive performance and calf survival using a longitudinal field study of cow-calf herds in Western Canada; PLoS ONE doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219901).

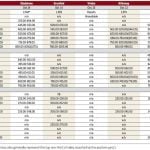

What they did: The research team worked with 105 cow-calf herds across Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Over the next four years, participating producers were surveyed about the start and end of the breeding season, pregnancy rates, and calf survival among cows and first-calf heifers. Data were analyzed based on herd size (herds with less than 300 breeding females vs. 300 or more) and when the breeding season started (April or earlier, May, June and July/August).

What they learned: Cow pregnancy rates were similar in small and large herds, but large herds were more likely to have more open heifers than small herds. Average cow pregnancy rates were highest (94 per cent) when the breeding season started in May or June and lowest when the breeding season began in April or earlier (93 per cent), or in July/August (92 per cent). Heifer pregnancy rates were also lower when breeding began in July/August (87 per cent) compared to earlier (92 per cent). The top 25 per cent of producers achieved pregnancy rates of 95 per cent in both cows and heifers.

Calf death losses in the first 24 hours after birth were lowest (1.7 per cent) on average among cows bred in July/August, intermediate in cows bred in May (2.1 per cent) and June (1.9 per cent), and highest (2.5 per cent) in cows bred in April or earlier. Calf death loss among heifers was the same regardless of when breeding started. Death loss in the first 24 hours was similar regardless of herd size, and the top 25 per cent of producers lost fewer than one per cent of calves born to cows, and zero per cent of heifers’ calves.

Calf death losses from 24 hours to weaning were lowest on average in calves born to cows bred in July/August (1.9 per cent) and got progressively higher the earlier the breeding started (2.3 per cent in June, 2.7 per cent in May, 3.5 per cent in April or earlier). Death loss was lowest in calves born to heifers bred in May or June (2.5 per cent to 2.3 per cent), higher among calves born to heifers bred in July/August (3.1 per cent), and highest in calves from heifers bred in April or earlier (4.4 per cent). Herd size did not affect calf death loss among cows but was higher in heifers’ calves from large herds. The top 25 per cent of producers lost one per cent of calves from cows, and zero per cent of heifer’s calves.

What it means: Shifting from winter to spring calving has improved the health and survival of beef calves in Western Canada. Calving on pasture reduces disease spread, and fresh grass supports colostrum and milk production. Late spring calving avoids more snowstorms and death losses. But breeding cows in late summer (for late spring calving) may reduce pregnancy rates because pasture conditions and nutritional value are starting to decline. Rebreeding success is much higher when cows are on a rising plane of nutrition, i.e. as pasture conditions improve in late spring and early summer. In late summer, forage fibre content generally starts to increase, digestibility decreases and protein levels drop. It will be even more challenging to rebreed heifers raising their first calf at this time, since they’re still growing themselves and have higher nutritional requirements than mature cows.

A simple delay in the breeding season may require other management practices to change in order to avoid unintended drops in reproductive performance. Careful and well-planned rotational grazing management that keeps forage vegetative (instead of mature and heading out) can help ensure cows are on a rising plane of nutrition into later breeding seasons. Supplementation may be needed on pasture, particularly in drought years. Addressing these challenges will require veterinarians, reproductive specialists, animal nutritionists, forage breeders, grazing experts and economists to work together to understand and best manage the whole system.

The Beef Research Cluster is funded by the Canadian Beef Cattle Check-Off and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada with additional contributions from provincial beef industry groups and governments to advance research and technology transfer supporting the Canadian beef industry’s vision to be recognized as a preferred supplier of healthy, high-quality beef, cattle and genetics.