When the Shetland Creek wildfire started in the summer of 2024, T.J. Walkem waited and watched smoke smudge the sky. Dry, hot and windy conditions fed the fire, and overnight, it doubled in size. Walkem and his father rushed to evacuate their cattle, surrounded by walls of flames.

“We’ve had a few (wildfires) the last couple years, and they have been catastrophic,” Walkem says.

Due to the frequency of wildfires in British Columbia, the B.C. Cattlemen’s Association has established programs to help ranchers during emergencies, including the Range Rider program.

‘Right in front of the flames’

Read Also

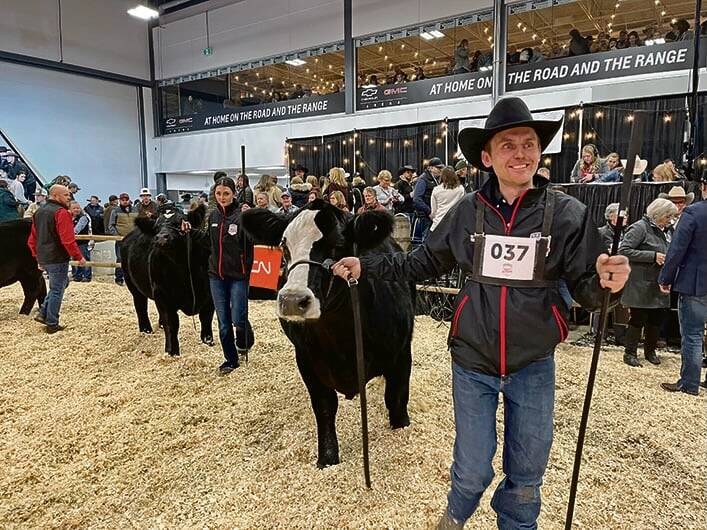

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

T.J. Walkem has been hit hard by wildfires in recent years. The Lytton Creek wildfire in 2021 swept in and forced Walkem to evacuate his cattle and scorched part of his range, located near Spences Bridge, B.C.

Again in 2024, he was forced to evacuate, with even more of his range reduced to cinders.

“2021 we were able to get out five hours ahead of the fire. And then this last year, we were right in front of the flames. So it was quite a different experience altogether.”

When the 2024 fire started to grow and move towards Walkem’s ranch, he decided to move their herd to the end of the valley because he was concerned the fire was getting too close to their access point. They continued watching, tension growing.

When they finally did have to evacuate, it happened fast. Suddenly the fire was right across the valley and travelling northeast, toward the cows.

“So then it was a mad panic to get down and get hooked up to the trailer, get the horses ready and get up to the end of the valley to get them out before the fire came through.”

The devastation from these wildfires have left lasting effects on Walkem’s ranch. In 2021 and 2023, the provincial government provided compensation for damages caused by the fires. However, in 2024, there was no financial assistance Walkem could rely on — a major challenge when so much of his range was burned by the fires. Walkem says they’ve spent a lot of their own money trying to restore grass in burnt areas. They’ve also had to find other pastures.

“So that’s a financial burden on paying for pasture, paying for feed, hauling and all that kind of stuff.”

There has also been a financial burden with losing cattle, both during the 2024 fire and afterward. “We lost cows in the feedlot due to stress, because everything got sick.”

In 2021, when they received some compensation, they were able to get their cattle out sooner, with less stress, and so suffered fewer losses. “This year we were not compensated, and we had the most stuff happen.”

Range Riders

Kevin Boon, the general manager of the B.C. Cattlemen’s Association, says the Range Rider program started because they needed experienced people to help get cattle out of wildfire zones. The program was launched in 2021 alongside other programs, such as the Rancher Liaison program.

“We hire people who supply their own horse or quad and are able to go out and help the ranchers move the cattle in off the range,” Boon says.

He adds that the range is “vast and extremely rugged,” so they need “good, experienced people to be able to do it.”

Riders are experienced and get paid for their work. They must show the B.C. Wildfire Services they are capable and experienced, before being approved. Generally, ranchers find the people who will ride for them, and they get paid after the event.

“It’s really hiring a cowboy,” Boon says.

Walkem took advantage of the program while dealing with the fire in 2024, with friends and neighbours helping evacuate his herd. He sees many benefits from the program.

“It’s pretty simple to use… it’s essentially like documenting employees. And then you fill out the paperwork, send it in, and then B.C. Cattlemen’s pay the riders.”

Rider experience

Rhonda MacDonald has experience with the Range Rider program, both as the rancher in need and as a rider.

She ranches with her husband on their cow-calf operation near Merit, B.C., where they have around 150 head. They used the Range Rider program in 2021 when the Lytton Creek wildfire threatened their operation.

The help they received was monumental. It saved many of their cattle and allowed their operation to survive.

“They come with their best horses, their best dogs, and the majority of them come with skills as well,” MacDonald says. “We had some hardcore cowboys come and help us out, and I know that due to not only their riding and horsemanship skills but their dogs, we saved, I bet, twice as many cattle as we would have if we hadn’t had the extra help.”

Usually, an evacuation includes a safety meeting to get a basic idea of the terrain, and if needed, extra horses are hauled in.

She said the compensation portion is important. While most people don’t ride for their friends and neighbours for the money, having a financial component allows for better, more prolonged help, and is beneficial for those who may end up with economic challenges because of riding.

“They are spending their time, their fuel, they’re putting wear and tear on their animals,” MacDonald says. For example, one rider had to retire his mare because of smoke inhalation. “She’s got chronic lung conditions now, so compensation is important.”

The program also pays for people who use ATVs, which is helpful because they are usually the ones who ride ahead to look for cattle and scout where the fire is.

In 2024, MacDonald rode for Walkem for three days as they rushed to evacuate his cattle from the valley. MacDonald said they were evacuating cattle with fire on either side of them, but with a good team, they made a difference.

“I’m happy to say that we saved quite a few head for T.J. … the last day that we were there, we saw some pretty awful things with burnt feet and burnt udders and a couple of animals that had to be destroyed on-site, but that’s also why we’re out there, to help the owners find those animals and identify them, and not prolong any suffering.”

Facing another season

For both MacDonald and Walkem, the concerns continue as they enter another wildfire season. The 2021 fires burnt 85 per cent of MacDonald’s range and killed 20 per cent of her herd. Plus, the fires damaged the topsoil. Walkem, too, only has one range tenure that hasn’t been burnt.

According to Natural Resources Canada, the number of wildfires has been decreasing since the 1980s, but the amount of area burned has increased, as has the number of disastrous wildfires. Canada’s 2023 wildfire season was the most destructive ever recorded, with over 6,000 fires torching 15 million hectares of land. Record high temperatures and dry conditions intensify the severity of these wildfires. Research done by Natural Resources Canada found that “climate change made the extreme intensity of (the 2023) fire season at least two times more likely than under pre-industrial climate while the persistence of these conditions were at least seven times more likely.”

For those who have already been devastated by the effects of wildfires, such as MacDonald and Walkem, the prospect of more fires is a heavy weight.

“I’m kind of putting all my eggs in one basket,” Walkem says. “If a fire is poorly managed, and the way that these fires are burning, my entire herd could be wiped out, and it’s out of my control. That is a big worry.”

MacDonald expressed concern with how wildfires are being dealt with, though she is thankful for the hard work of the crews on the ground.

“I feel like not only are (wildfires) more frequent, but the way that they’re handled has changed. It seems that B.C. Wildfire Service is not about putting out the fires anymore. They are about trying to manage them, and, frankly, it doesn’t work. During the 2021 fire that we dealt with, we saw a lot of mismanagement on B.C. Wildfire Services part. And there was very little acknowledgement of local knowledge, and it basically cost us.”

However, they know they are not alone — they have the support of each other, and other producers who will drop everything to help at a moment’s notice.

“It feels like a blessing to be involved in the ranching community most of the time, and sometimes bad events really do bring out the best in people,” MacDonald says.

“With wildfire, it could be any of us that it happens to, and people are always willing to help.”

Resources and programs

There are other resources available from the B.C. Cattlemen’s Association for ranchers dealing with the effects of wildfires. A notable one is the Rancher Liaison program, in which a rancher passes information between the B.C. Wildlife Service Incident Management Team and affected ranchers, and vice versa. This is an important program whenever there is a prescribed burn or when livestock need relocation.

There are also livestock relocation services, and a service that locates feed, especially when cattle must be moved. These services are in collaboration with the provincial government.

Kevin Boon, B.C. Cattlemen’s Association general manager, says something many people don’t think about is how emergencies can affect a rancher’s mental health. Because of this, the association works closely with AgSafe to make sure there are mental health resources available for those who are dealing with the aftermath of a wildfire.