The science of beef cattle genetics has sped up rapidly since the bovine genome was first mapped in 2009. Now it’s time to put that knowledge to work on farms and ranches with genomically enhanced expected progeny differences (EPDs). That was the main message presented to producers at a couple of recent gatherings in Regina and Edmonton.

Genomically enhanced EPDs look and read like traditional EPDs from your breed association but these ones are bulked up by massive amounts of genetic data.

Producers simply submit their pedigree and performance data as they normally do to their breed association. If the animal has been previously genotyped or is related to an animal that has been sequenced and is in the database the genetic and phenotypic information is merged to create an enhanced EPD.

Read Also

Fog fever, or ‘the grunts,’ spells trouble for beef cattle

Whether you call it fog fever or something else, this illness means trouble for cattle. Learn what triggers the disease and how to prevent it.

Genotyping is commonly known as DNA profiling because it looks at multiple traits. The results are expressed as molecular breeding values (MBV) for each trait. The numbers alone don’t mean much unless they are ranked against MBVs of other animals in a reference population.

MBVs are predictions of an animal’s own genetic merit, which, on average, is about half the equation in its offspring. EPDs, on the other hand, incorporate data from an animal’s sire, dam and their relatives down the lineage with the animal’s own record to predict performance of its offspring.

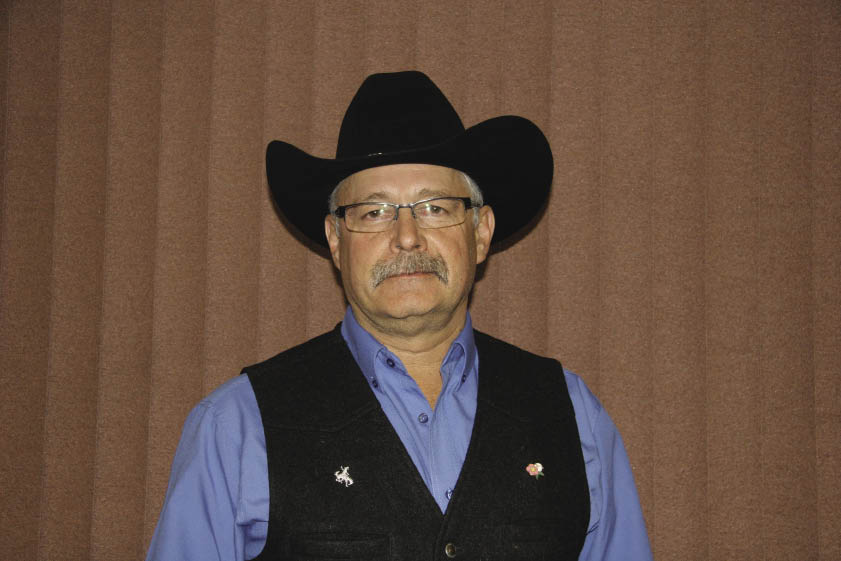

“MBVs are not meant to replace EPDs, but will help make EPDs more predictable,” says Dr. Les Byers of Vegreville, Alta., manager of veterinary services, beef cattle and beef genomics for Zoetis (formerly Pfizer Animal Health). Zoetis markets a high-density (50K) genomic panel for genotyping Angus cattle.

Byers says genotyping immediately increases the accuracy of an EPD. It’s the same as instantly adding the records from 15 to 30 offspring (depending on the trait) to the accuracy of a bull or heifer’s EPD before it even produces a calf. That’s more calves than a natural-service bull produces in a year or one cow produces in a lifetime, he adds.

“By not using genomics, we are making mistakes,” says Byers. In one trial, he says, specific criteria were identified for selecting yearling bulls and potential candidates were pulled from a group of candidate sires. Based on their traditional EPDs, 95 bulls met the criteria and 368 didn’t. When the bulls were genotyped with a high-density panel to improve the accuracy of the EPDs only 62 of those 95 bulls met the criteria, and 44 of those that had been culled now passed the test. In total, they had 106 bulls from which to choose versus the initial 95 selected using traditional EPDs.

In the same way, genotyping can be used to select superior replacement heifers and cull bottom-enders.

In the big picture, these genetically spiked EPDs will speed up genetic progress on farms and within the industry as a whole.

More from the Canadian Cattlemen website: Keeping it simple with F1s

Byers says sales of their high-density Angus panel to seedstock producers are growing, and the price is coming down, but it is the demand from commercial bull buyers for this genetic information that will drive the spread of this technology.

Lower testing costs and the fact DNA can now easily be extracted from a few hair follicles and tissue punches are behind the increasing use of gene panels for parentage testing. Some breeds now require DNA to register an animal.

It is also being used in large commercial herds to identify sires in multi-sire breeding pastures or cleanup bulls after AI breeding. It this way it can help sort out the least prolific sires, identify heifer bulls, and find sires whose daughters deserve a place in the breeding herd.

Tests for the leptin gene and marbling are currently being used to manage groups of calves in feedlots.

Challenges

One very real challenge to adopting this technology is the fact that many producers don’t yet fully understand or use EPDs.

“Some producers really dive into EPDs; some don’t even look at them because either they don’t care or find all of the numbers too overwhelming; and others trust that EPDs work and figure using them is a good way to select cattle that fit their goals,” says Tom Lynch-Staunton, director of industry relations for Livestock Gentec at the University of Alberta.

As a result the goal for breed associations and anyone involved in extension today is to get people thinking about genomic improvement and how they can use a combination of genomics, performance records and visual appraisal to find the best animals for their operations, says Lynch-Staunton. “The use of genomics won’t replace cattle shows. An animal could have a great genomic profile, but not be functional. Genomics is a complimentary technology, not a competing technology.”

Another underlying fear is that genomics will eventually reduce diversity within the beef herd as it has done with dairy, pork and poultry.

Lynch-Staunton says beef cattle are different. Those other industries were quick to adopt genomics because of their uniform production systems whereas beef cattle are raised in all sorts of systems and environments.

Each breed has strengths in certain traits and time will tell what value the industry places on those strengths and what each breed has to offer. With genomics those strengths can be identified and preserved through selection to maintain diversity within breeds and purebred lines by mating unrelated animals.

As it stands, a bull is two years old before his first calf hits the ground; four before those calves are harvested; and maybe seven before his offspring add to the accuracy of his EPD. By then he could be long gone and there’s no getting back the exact same genetic makeup.

Three steps to getting started

Lynch-Staunton says the genomics of tomorrow will be even more exciting than what is available today. In the near future we could have genetic evaluations that screen for improved feed efficiency, immune response and carcass traits.

To those who want to catch hold of this future, his advice is to start slow. Don’t rush out and have a bunch of profiling done.

Instead he suggests three steps to maximize the value of DNA testing.

Start by getting all of your paper records into an electronic format. This electronic data can now be used by a breed association to generate traditional EPDs for your cows, or rank the cows and heifers. Breed associations, the University of Alberta, and private companies offer this service for commercial herds.

At that point you are ready to have your DNA test results merged with your EPDs to create genetically enhanced EPDs for your herd to select bulls, cows and replacement heifers that fit with your goals.

The easiest way to use this new technology is to buy bulls and replacement heifers with EPDs and preferably genetically enhanced EPDs for the traits that are important to you.