Prior has been using intensive grazing on his 90-acre farm, Grazing Meadows in Brussels, Ont., for over 15 years now. His cattle rotationally graze on 30 meadows, located along the laneway, using a leader-follower system. Stock is shifted daily, giving each paddock up to 30 days of rest and recovery. Each paddock is about 1.5 acres in size, and is surrounded by electric fencing, which easily controls stock.

“Stress is a huge factor in gain in cattle,” says Prior. Daily movement helps to tame stock, which reduces stress and results in more weight gain.

Read Also

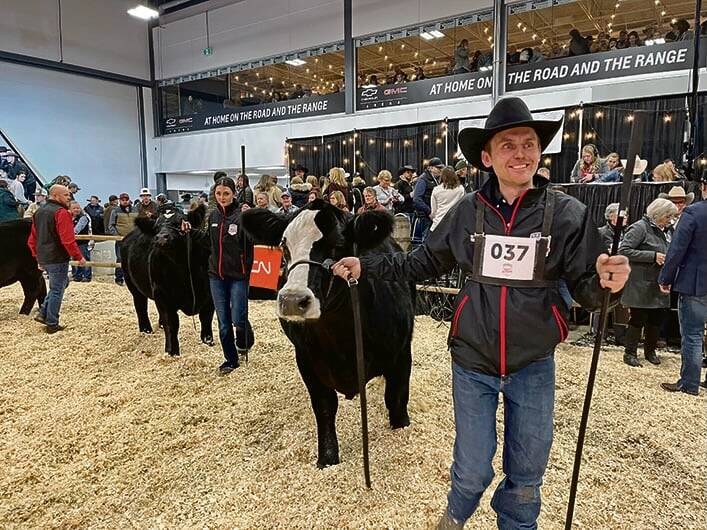

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

Fresh, clean water is another key to cattle performance. Typically, beef producers in this area fence the perimeter of their land and turn the cattle out to graze as they wish. Water is kept in one spot and the cattle walk to the water whenever they’re thirsty.

“What’s different with our system is that we take the water all the way out to the cattle,” he says. “We’re not running a weight loss clinic here with our cattle. We want them to gain as much as they can.”

Prior says that his grazing method gets him double the production per acre. He knows because he uses scales to measure their growth. Just as cash croppers measure in bushels per acre, beef producers, he says, measure in pounds of meat per acre. Using his system, Grazing Meadows has yielded 500 to 650 pounds per acre. Over the past 10 years, his cattle average a gain of 354 pounds or 2.46 pounds per day over 144 days on grass.

Management is the key to a successful grazing system, says Prior. Moving his cattle daily allows for better species diversification, which, in turn, provides a variety of nutritious feed for his cattle. Pasture species include perennial ryegrass, reed canary grass, orchard grass, tall fescue, white clover and chicory. Minor species include alfalfa, bird’s-foot trefoil, Kentucky bluegrass, Matua prairie grass, creeping red fescue and crown vetch. And more often than not, plants are rested more than they’re grazed, which means that regrowth isn’t an issue.

More from the Canadian Cattlemen website: The grazing plan

Besides species diversification and better nutrition, there are many benefits to using Prior’s system. Grazing does not require confinement barns. It uses less machinery, which lowers the cost of fuel and repairs. Because he has healthier animals, his system also has fewer vet bills. Overall labour costs are lower, as is the cost of feed, since there’s a decreased demand for grain and supplements. Finally, Prior’s system saves on manure handling. He says that 90 per cent of nutrients — which are evenly spread around by the cattle themselves — are returned to the soil through urine and feces.

In fact, Prior did the math on manure distribution. For him to get one patty per square yard in a continuous grazing system would take up to 27 years. In his intensive system, grazing a maximum of two days per paddock, it would take just two years to get the same coverage.

Prior’s system also allows him to turn his cattle out earlier in the spring, which helps control grass growth and introduces new feed slowly. If the grass growth is ever too slow, he has a hay field ready for use.

When Prior speaks to beef producers he’s usually hit with questions about time and money. Specifically, producers want to know how much a system like his will cost them, and how much time it takes to rotate cattle daily.

“In 10 minutes I can be out in my vehicle, move the cattle, move the water, and be back to the house again,” says Prior. “If you’re going out to look at your stock every day anyway, I don’t think that time is a consideration.”

Prior broke his costs down for the nearly 100 producers at last year’s Ontario Cow-Calf Roadshow. To have fencing installed for 100 acres will cost you about $29,000, he says — and that fencing will last for years. The fencing at Grazing Meadows is going into its 17th year and is still going strong.

“Plus,” says Prior, “those extra costs are well paid back with the gains you’re getting in production.”

Grass seed is another cost. Prior spent about $5,400 on grass seed for 90 grazeable acres. The moveable watering system set him back some $2,900. At a total of $37,300 amortized over 10 years (a number that includes fencing), it costs Prior about $41.44 per acre per year. Custom feeding, on the other hand, is usually based on dollar per pound gained, and can be much more expensive with decreased results.

Finally, his system helps preserve the land around him. Intensive grazing systems like his reduce selective grazing and provide adequate recovery time for the plants, reduce soil erosion, and meet the physiological needs of the cattle themselves.

It also reduces the need for machinery and fuel. Prior says he only needs one type of farm machine — a four-legged forage harvesting dung spreader.