A year ago beef producers in parts of Alberta and Saskatchewan were thrown for a loop when an Alberta cow tested positive for bovine tuberculosis (bTB) at a U.S. packing plant.

The ensuing disease investigation by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) quickly became the largest and most complex beef cattle investigation in its history, says Alberta Beef Producers’ beef specialist, Karin Schmid, who has been the industry’s liaison with the CFIA for this investigation.

The investigation along with routine surveillance at packing plants for bTB lesions are key parts of Canada’s bTB eradication program. National control efforts date back to 1923, but the real turning point in the battle with this disease occurred in 1978 when a herd depopulation policy came into effect. By 1985 the World Organization for Animal Health Canada declared Canada statistically free of bTB.

“This case doesn’t change that,” says Schmid. “But the thing with eradication programs is we have to take what may at the time seem like severe steps to make sure we are stamping it out so we don’t get reoccurrences that could affect our trade status.”

Read Also

Treaty Land Sharing Network expands reach in Saskatchewan and Alberta

The Treaty Land Sharing Network, which connects land holders with First Nations and Metis people, has expanded since it began in 2018

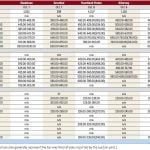

As of August 11, 11,500 cattle had been tested and humanely slaughtered, including all cows and calves from the original infected herd, which has six confirmed-positive cases to date, and 18 high-risk herds that had some direct contact to the first herd.

High-risk herds were “presumed to be infected” by commingling with the infected herd on community pasture in the past five years giving them an equal risk of exposure to the disease.

All reactors to a caudal-fold skin test were re-examined to confirm the bacteria were the same strain as the first case.

The meat from non-reactors was permitted to enter the domestic food supply.

Approximately 500 of the 11,500 cattle tested were reactors and came from either herds that had fence line contact with the infected herd or were trace-out herds that took in cattle from the infected herd in the past five years. Post-mortems were done on all 500 and tissues tested when indicated.

Schmid says it’s not unusual to get two to four per cent false positives with the caudal-fold skin test due to cross-reactions with mycobacteria species, other than Mycobacterium bovis, the bug that causes bTB.

Followup blood tests helped screen out false positives or at least narrow down the number of false negatives. The final diagnosis is confirmed by culturing lymph-node tissue to see if the mycobacteria will grow within 12 weeks.

Infected and presumed-infected premises remain in quarantine until they are cleaned up and disinfected and stay clean for 45 days at an average 12 C, at which point they can be restocked.

Trace-out herds are quarantined until the testing is completed. By August 11, 92 premises with approximately 17,500 animals had been released from quarantine with tests on another 1,000 head on 13 sites still being processed.

There is an option for early release from quarantine when reactors show no signs of disease upon post-mortem although certain records must be kept until culture tests confirm the negative status. Some producers turned down this option.

As of mid-June, CFIA had paid out $37.2 million in compensation for animals ordered destroyed. Another $5.9 million was paid out through the Canada-Alberta Bovine Tuberculosis Assistance Initiative to cover extraordinary costs involved in feeding and caring for quarantined cattle, cleaning and disinfecting the premises, and interest on loans.

Trace-in testing underway

Schmid says trace-in testing of operations that supplied cattle to the infected herd in the past five years will start in September and is expected to wrap up in February.

Testing of this group was postponed until fall to avoid putting additional stress on the cows during calving and so they could go to pasture.

One trace-in herd of special interest because it was the birthplace of one of the six positive cases on the infected farm was tested early on and found to be free from bTB.

There are as many as 200 trace-in herds of interest covering some 60,000 animals. Most are in Alberta and Saskatchewan, with a couple in British Columbia and Manitoba. As a first step the producers completed epidemiological questionnaires during the summer to establish or refute their possible connection to the infected herd.

These herds will be placed under quarantines for about four weeks as the cattle are being tested. CFIA staff hope to begin testing about 10 new herds per week.

Animals that test positive will be subject to post-mortem and further laboratory testing, which could extend the farm’s quarantine period up to four months.

Delaying the testing of trace-in herds may seem somewhat counterintuitive, but as Schmid points out these herds are considered low-risk, the same as any herd with no known contact with the index herd in the past five years.

“Had the disease been simmering in another herd somewhere, it would have been caught at slaughter through routine surveillance,” she adds.

No direct link or smoking gun has been found so far and, in truth, Schmid says the source of this infection may never be found.

Wildlife doesn’t seem a likely source. More than 1,250 elk taken from the Suffield base since last fall showed no signs of infection.

The strain of Mycobacterium bovis in Alberta was first seen in Mexico, but that’s not to say that it came to Canada from Mexico. It has since been detected in cattle in some U.S. states as well.

For more details on the current situation, visit www.inspection.gc.ca and search for Bovine TB Investigation-Western Canada.

We’ve learned a few things

“We had a very good meeting with the CFIA, industry groups and some producers in the room to talk about what we could do better in future events and how we could make the fall trace-in investigation go more smoothly. Communication was the big one,” Karin Schmid told the audience at the University of Calgary’s beef cattle conference in June.

After getting off to a rocky start, the CFIA soon began holding industry calls at least weekly, attending town hall meetings, and posting detailed information on its website.

“They got very good at sharing information and inviting me to meetings,” she says. Schmid, in turn, began posting updates to share with producers via email, media and the Alberta Beef Producers website.

She was unable to pass on any information to those directly affected due to privacy laws, unless they signed up for her email feed.

“This is a very difficult situation for the producers, but they and their communities really banded together to look after each other and showed strength, resilience and patience with the process,” she adds.

“It’s also very hard on the people doing the investigations… trying to sort out herds to try to save some of the cattle.”

That raises a point in favour of traceability and keeping good records on the movement of animals. In a couple of instances, producer records did save parts of their herd from depopulation.

If the agreed-to Cattle Implementation Plan had been in place — basically reading cattle in at new premises — Schmid believes the investigation would have been completed by now.

The caudal-fold skin test is the internationally accepted screening test for bTB, however false positives with this test are a problem. CFIA regularly examines new live-animal screening tests as they appear; however, many of the tests developed in other countries over the last 30 years aren’t sensitive to the strains of Mycobacterium bovis seen in Canada.

Policy updates are likely to stem from this investigation, as well. For example, horses, dogs and cats on infected premises will be considered low-risk unless there is reason to believe otherwise. Trace-in and trace-out activities are being limited to the original infected herd instead of involving all of the presumed-infected herds.

Compensation programs need some work, as well. The outstanding question is whether extraordinary costs producers face when placed under quarantine should be covered under the regulations.

Finally, work is progressing on formalizing industry’s involvement in the emergency operations centre for future animal health events. “I can’t say enough good things about this process,” says Schmid. “We learned a lot from the CFIA and they learned a lot from us.”