If an animal has a health problem, it’s crucial to have the correct diagnosis before attempting treatment. Dr. Chris Clark of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine in Saskatoon says the most common reason that a treatment fails is a wrong diagnosis.

“We often complain about disease not responding to treatment. But the drugs we have are fairly effective. If the animal is not getting better, it’s probably because you are treating it for the wrong thing. For instance, there are a lot of diseases that don’t respond to antibiotics. They are amazing drugs but they don’t affect viruses, parasites or nutritional problems. “They only treat a bacterial infection — and only certain types of bacterial infection,” he explains. You have to select an antibiotic the bacteria are susceptible to.

Read Also

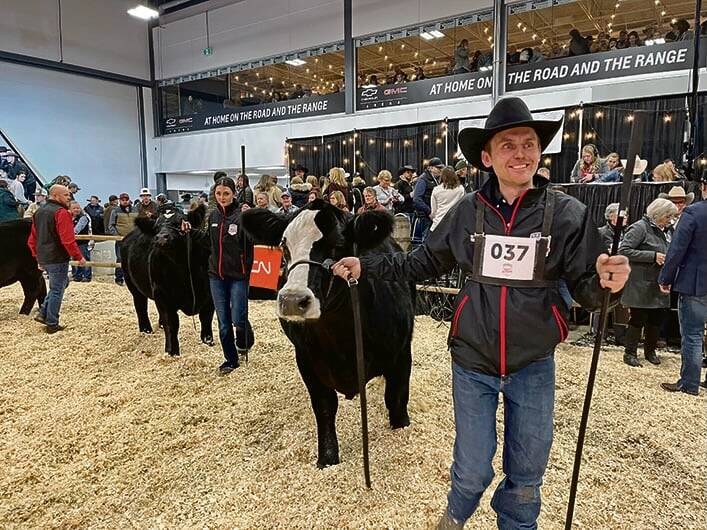

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

“Also keep in mind that with some bacterial infections, the tissue is so rapidly destroyed that treating the bacteria is not the issue; pathology is the problem. An example would be an infection in the joint of the foot. Even if you can eliminate the infection, there is still residual damage, making the animal lame,” he says.

“Diagnosis can be difficult. It takes four years of vet school for us to even come close. It’s not something that can be taught instantly. A person needs experience as well as classroom study, and cattle producers must recognize the difference between a presenting sign and a diagnosis,” he says.

“Cattlemen generally have a set of skills that are very hard to teach. I would love to have the skills they have — being able to tell when an animal is a bit ‘off’ and not acting quite like it usually does.” It helps to observe the herd from afar, before the animals notice you, because an alert animal may mask the signs of sickness. Astute observation is a skill most stockmen have.

- More cattle ‘Health’ with Canadian Cattlemen: Hunting for Johne’s disease in Saskatchewan

“The rancher has this ability to pick up on subtle signs that the animal is sick. They can identify the one animal in the herd that is not behaving like it normally does, or behaving differently from the other animals. Stockmen can often identify which organ system is involved — whether it is lame, or showing signs of respiratory disease. They know if the animal is coughing or has a weepy eye, or diarrhea,” says Clark.

“But as a veterinarian my job is to determine why it has a weepy eye, why it has diarrhea, why it is lame, or coughing. Diagnosis is all about the why. This determines the treatment. There is no treatment for lameness, per se. If the animal has a nail in its foot, the nail has to come out. If it has foot rot it needs antibiotics. If it has a broken leg it needs to be euthanized (unless it’s a small calf and the leg could be splinted). We don’t treat all lameness conditions the same way,” he says.

“There are also symptomatic treatments. If an animal is lame you can give it Metacam, to provide pain relief. But this won’t solve the underlying problem. You are merely treating the symptom and not the disease. There are treatments for diarrhea that make good sense — such as giving fluids/electrolytes — but knowing the cause of the diarrhea allows you to more specifically tailor your treatment.” You would treat it differently if it is caused by a bacteria than if it’s caused by coccidiosis or a virus, or worms.

“This is why diagnosis matters. Most people look at a lame cow and assume it’s foot rot. However, foot rot is a very specific disorder. If it’s foot rot, it will get better with antibiotic treatment. If a producer calls and says, ‘Doc, I’ve got a cow with a bad case of foot rot that I’ve been treating for a week,’ then I know it’s not foot rot. It’s either something else, or it’s been neglected too long before treatment was begun and it has gone into the joint. Recognizing foot rot is highly important, so I teach people some of the clues,” he says.

- From the Manitoba Co-operator: Frozen ears and feet – but not from the cold

“When an animal gets foot rot, the key thing is swelling above the hoof. The swelling is symmetrical and affects both digits, forcing the claws apart. If you look closely at the foot, you will see a grey-green slimy mass sticking out from the skin between the claws. If you give that animal antibiotics the foot will get better. Anything else that’s causing lameness needs to be looked at by a veterinarian.”

Abscesses are probably the most common cause of lameness that’s not foot rot. “But you can’t treat an abscess with antibiotics successfully, even though it’s a bacterial infection. The infection is walled off from the blood supply and the antibiotic can’t get to it. Until you drain the abscess, the animal will get no relief,” he explains.

With eye problems, producers need to know the difference between pink eye and cancer eye. “Pink eye is treatable (and often transmissible to other cattle in the summer). Cancer eye in early stages can be treated, or you can put that animal on the cull list. If you see an animal with a weepy eye, take a close look. If it’s not cancer eye or pink eye, lift the eyelid to make sure there’s not a seed head, barley awn or some other foreign object stuck there and scratching the eyeball every time the animal blinks. If there’s something there, just lift it out.”

Calves tend to go downhill quicker than adults if they get sick, because they don’t have the body reserves. “If an animal is ill, your best diagnostic tool is a thermometer — just a simple one you can get at the drugstore. Mark it with a Sharpie pen so you don’t get it confused with one in the house. The new ones are nicer than the old rectal thermometers that you had to tie a string on; the new digital ones widen out and you won’t lose them in the cow’s rectum,” says Clark.

“Taking temperature is easy and can tell you a great deal. Body temperature for cattle should be between 38 and 39.5 C. If a young calf is cold, with subnormal temperature, that’s life threatening. If the temperature is above 39.5 C it’s running a fever. The most common reason for fever is infection. It could be viral or bacterial, but if the calf is running a fever, treating with antibiotics is a good idea. If the calf does not have a fever, there is a question whether antibiotics will help. So the first step is to take that calf’s temperature,” he says.

If you call your veterinarian for advice, report the animal’s temperature. “This gives the veterinarian a lot of information. When we know the temperature along with your description of symptoms, this helps us narrow it down,” says Clark.

“With young calves that aren’t doing right, check the navel. This is a common site of infection. Learn to tell the difference between a navel infection and a hernia. When you squeeze them, hernias generally disappear; the protrusion moves up into the belly. It’s normally soft, rather than hard and hot. The amount of skin at the navel is variable with the breed. What you are interested in, rather than how large the area, is the stalk that you can feel under the skin. It should be thinner than your pinkie finger, and should not be hot or painful. If it’s thick, hot, or painful when pressed, or has a discharge from, it’s probably infected,” he says.

“If it’s a small hernia, the only thing in it is a bit of fatty tissue (omentum). If it’s a large opening, a loop of intestine may come through and become twisted — and that’s life threatening.” A large hernia needs surgical repair.

Pneumonia in calves occurs most often in winter/spring rather than summer. “If the calf is sick in summer it’s usually something else. The thing about pneumonia is that it always gives the calf a fever,” he explains. A thermometer will be a big help.

Scours in calves is caused by multiple things, so knowing the age of the calf and the management can help a veterinarian determine the most likely cause. “If the calf is more than three weeks old, you may be dealing with coccidiosis, whereas under three weeks it is more likely caused by a virus or bacteria. The thing to realize about scours in young calves is that it’s not the scours that kills them. It’s the dehydration. When you look at a calf that’s got scours, it doesn’t matter how shitty its tail is, or what the scours looks like. What we need to check for is dehydration,” says Clark.

“Look at the eyes. When a calf suffers from dehydration it looks like the eye sinks back into the socket. If there is a gap between the eyelid and the eye (a sunken appearance), that’s a bad sign. The second way you can check is take a pinch of skin on the side of the neck, and let it go. It should spring back into place instantly. If it takes a few seconds to spring back, you are dealing with dehydration,” he explains.

“Those calves need fluid/electrolytes, given by stomach tube; don’t try to feed the calf a bottle. That would take you an hour and you’ll end up wearing most of it because the calf won’t want to suck it — and you’ll complain about the effort and never do it again. With a stomach tube you can give a calf two litres of electrolytes in less than a minute. If something is easy, you’ll do it again,” says Clark.

“Another thing I tell people regarding field diagnosis, if they wonder when to stop treating a calf — it’s when you can no longer catch him. If you can’t catch him, don’t treat him. If he’s easy to catch, he needs treatment. I also recommend talking to a veterinarian if you have repeated episodes of the same problem,” he says.

“When you ask your vet for advice, describe what you are seeing. Don’t say, ‘I’ve got calves with pneumonia.’ Tell the vet that you have calves that are depressed and not sucking, and are doing this, this and this (and what the temperature is). Work with your veterinarian to get the diagnosis. If you say your cow has foot rot, this is a diagnosis rather than a description of the lameness, and won’t enable your vet to help figure it out,” he says.

“We want producers to recognize the value of a diagnosis, and get involved in helping their veterinarian make the diagnosis.” The producer and the veterinarian can work together as a team. Producers need to describe, to their best ability, what they are seeing, so the veterinarian can have good clues to work toward the proper diagnosis.

“A phrase one of my colleagues used a lot regarding diagnosis: more mistakes are made from not looking, than not knowing. You make more mistakes if you don’t look close enough at what the animal is actually doing or how it appears. The clues are often there, if you look for them,” says Clark. c