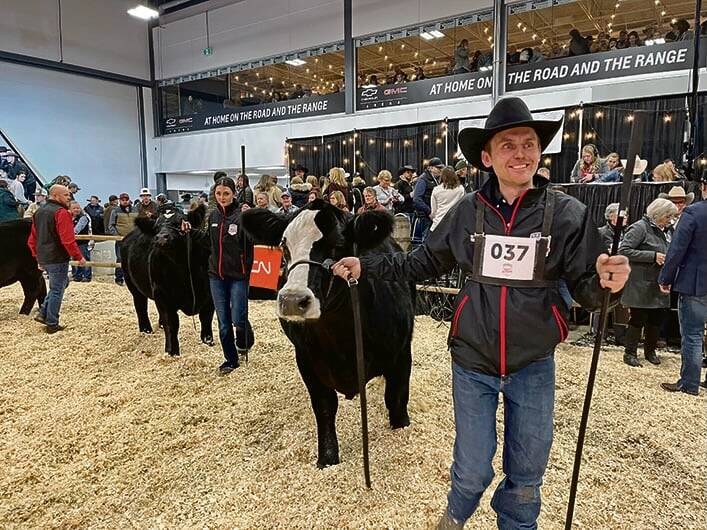

It’s early July 2024 and Cedric MacLeod is already preparing for winter. He’s knee-deep in harvesting hay and silage that will be bale feed for his herd in cold weather. Calving has just finished. Yesterday, the last calf of the season walked up to him in the field. He’s so fresh he doesn’t know who MacLeod is just yet.

MacLeod is a first-generation farmer and the owner of Local Valley Beef, specializing in grass-fed beef products sold direct-to-consumer in Centreville, N.B. He is also an agronomist providing consulting services in a region that goes heavy on potatoes. And, he’s executive director of the Canadian Forage and Grassland Association.

“I bought my first cow herd in February of 2003, and then BSE walked in the door,” MacLeod says. “Like everybody, we sold steers for 60 cents a pound, and we couldn’t sell heifers, so we retained them and grew the herd.”

Read Also

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

MacLeod says a friend who had just helped establish the Manitoba Grass Fed Beef Association suggested MacLeod try to direct market his first two-year-old fully finished grass-fed heifer.

“We started at one and then went to two and then four. Now we’re calving out 45 and everything is being sold off the farm,” MacLeod says. Last year, he kept several heifers to expand the herd.

The farm’s pastures are all intensively rotationally grazed to maximize their forage output and to manage risk for the hot, dry weather that occasionally strikes Eastern Canada. He manages roughly 400 acres every year, with 100 acres of pasture, 100 acres of stored forage, and another 200 acres of annual crops, forage seed oats, soybeans, and some fall rye for cover crop seed. MacLeod installed a solar water pumping system in 2006 and a winter water station in 2007 which supports a year-round grazing program.

- RELATED: Grazing management and soil health

“When winter comes around, the cows are well conditioned and robust and have access to the woods for protection, so we don’t have a barn. Our bale grazing program means we don’t have to spread manure, and we get as close to 100 per cent use of our manure nutrients as possible. We try to keep it real simple,” he says.

Direct marketing grass-fed beef

Differentiation matters when you’re building a brand. MacLeod works hard to share his farm’s story. For more than a decade, Local Valley Beef was one of a handful of local farms supplying a prominent hotel restaurant’s menu. The relationship helped build connections between travellers and the region’s local food story.

- RELATED: Direct marketing can pay off

“I market on what we are and who we are, not what other operators aren’t,” says MacLeod. “Everyone has a different production model. There’s lots of room. We’ve been working away, trying to maximize our profitability, and people seem to dig our story, so they buy our product.”

MacLeod says some of his customers are more mature clients who are interested in grass-fed beef from a health perspective. Some are new New Brunswickers who have moved from other provinces and are looking for a bit of local flavour. Despite rising grocery prices, business is steady. The farm’s order page indicates there may be a three-to-six-week delay on some orders, depending on inventory.

“Our clientele isn’t everybody,” says MacLeod. “To finish an animal on grass and manage the transportation and processing involves a lot. We do it a bit differently, so we charge a bit of a premium for that differentiation.”

The proving ground

One challenge of expanding a grass-fed beef operation in potato country is the limited land base available for forage crops.

“Prior to BSE, there were more cows on farms, and perennial forages played a greater role in crop rotations,” says MacLeod. “As the cattle sector has evolved, there are fewer cows on the landscape, requiring fewer forage acres and we’re missing that organic matter addition, and that positive impact on soil health. It’s starting to come back.”

He says it’s an exciting time for agriculture in his region where potato buyer McCain has put more focus on regenerative agriculture. McCain’s Regenerative Agricultural Framework has a goal of 100 per cent regenerative agriculture by 2030. The company says the framework aims to lift farm resilience, crop yield and quality by improving soil health and water quality, optimizing water use, enhancing biodiversity, and reducing the effect of synthetic inputs.

“Value chain players like McCain and others are asking their growers to do some different things, and the increased recognition of the importance of perennial forages in a rotation is pretty exciting,” MacLeod says.

MacLeod himself has run short on land for forages, so he approached a potato grower to see if he would be interested in developing a longer-term relationship to add some high-quality alfalfa forage to his rotation. Now every two years, the potato grower underseeds his oat crop to an alfalfa and grass mixture, providing a two-year break in his potato rotation.

“I rent the ground from him, buy the seed, he plants the alfalfa and I handle the cutting for two years,” says MacLeod. “We’re pounding out big forage yield, and it gives him an extended rotation with a perennial crop in the mix. Together we get free nitrogen, lots of organic matter and enhanced soil health. We know that when he puts in his next potato crop, he will be dropping that seed into a well-conditioned soil resource, so his potato systems remain resilient.”

The best part? MacLeod doesn’t care if it’s the grower’s field with the lowest yield. The idea of service crops — of skipping a grain crop and instead planting a crop to feed the soil — is a less popular practice, but MacLeod works with growers to help them understand how and why it works.

“Growers are fundamentally invested in advancing the health of their soils, as the lifeblood of their farm and our collective food systems. I am happy to play a supporting role in this effort, however possible, whether it be land trading, agronomy advice, or other.

“As an agronomist, I’ve always looked at my farm as a proving ground for the practices I’m promoting to my clients, and that’s all part of it,” says MacLeod. “At the end of the day, we are grass farmers. Cows help us manage that grass, and we treat them as partners in building and maintaining healthy and resilient soils.”

MacLeod farms in Carlton County, N.B., with his wife, Alanda, and his 10-year-old son Kalen.

– Lisa McLean is a writer and issues management professional who has worked with agricultural groups for more than 15 years. She lives in Guelph, Ont. You can find her on Twitter @lisammclean.