Frank Zhang says when he talks to his colleagues about silage, they all are familiar with barley silage — but none are familiar with rye silage.

“It’s very rare to find people using the rye silage,” Zhang says. “But thinking about the environment changing, just like the drought this year … this might provide an opportunity to provide a forage source for beef cattle.”

Zhang is involved in a study being conducted at the University of Saskatchewan for his PhD research under Dr. Greg Penner, looking at how hybrid rye silage compares to barley silage. On June 20, Zhang and Penner presented their results to attendees at the Livestock and Forage Center of Excellence Field Day near Saskatoon, Sask.

Read Also

The Canadian Cattle Association’s international advocacy efforts

Global ag policies affect Canadian food policy, so the Canadian Cattle Association participates in international and domestic forums

Hybrid rye silage

Penner says the hybrid rye silage research began when some of his colleagues were telling him about new varieties of rye, some of which were developed with forage applications.

“The potential opportunities that were associated with these rye varieties were a shorter pollination window, which should reduce risk for ergot contamination,” Penner says. “And ergot has historically been a challenge for using rye in diets for cattle.”

Penner, Zhang and others at the university went forward with research on this topic, running a two-year experiment, starting in the 2021-22 season. They got the hybrid rye into the ground by mid-August of 2021 to maximize forage production.

“What we did is try to set up a research program that was going to allow us to capture some representation of field yields, chemical composition and silage characteristics, and then evaluate how that silage would affect the performance of cows that were growing in a backgrounding program,” Penner says. “So this is a slower-growth program as well as a finishing program where the forage inclusion rate is much lower.”

In the spring of 2022, for the second year of the experiment, they seeded barley in addition to the rye. Each crop had a field-scale plot.

“We balanced those plots across multiple fields and tried to account for variability to make sure that we didn’t have an imposed bias for rye or barley,” Penner says. “We harvested the hybrid rye at an early dough stage, very early dough, and the barley at a soft dough stage for silage production.”

Results

Penner says they now have two years of data. Based on that data, it doesn’t look like there is a yield difference between barley or rye, though he recognizes that crop production has been abnormal the past two years due to dry conditions, which generally isn’t good for rye.

Because the barley was taken off in the soft dough stage while the rye was taken off at an early dough stage, they had different chemical compositions going into the bag. However, Penner says they both had good fermentation profiles and performed equally well.

For backgrounding cattle, Penner says 60 per cent of their diet was silage.

“What we did see is that as we increased the rye inclusion, we got a reduction in feed intake,” Penner says. “More rye results in cattle eating less and as a consequence, they grew slower and had a lighter body weight at the end of the backgrounding phase.”

On the finishing side, they fed 10 per cent silage instead, which is common for finishing diets in Western Canada.

“We saw again that we did have a reduction in final body weight, and we had a different response for growth where replacement of half of the barley caused a reduction of growth but replacement of 100 per cent of the barley silage did not reduce growth. So it seems to be a response to a combination of hybrid rye silage and barley silage having a depressive effect,” Penner says. “Regardless of that, there was no change in feed intake and, again, we saw equal feed conversions between cattle that were fed all barley silage or all rye silage.”

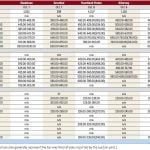

Zhang says they fed the cattle four dietary treatments and had preliminary results for some of the backgrounding steers. The steers, starting at a weight of 236 kilograms, were fed 100 per cent rye, two-thirds rye, one-third rye, as well as 100 per cent barley.

The results were that the steers that consumed the 100 per cent hybrid rye silage had an end weight of 429 kilograms, while the steers that consumed the 100 percent barley silage feed finished at 451 kilograms.

“What we see from the backgrounding is increasing the rye silage inclusion rate, the average daily rate of gain linearly decreased,” Zhang says.

Hybrid rye versus barley

Penner says there are different reasons why a producer might choose to grow barley or rye. He says a producer might want to grow hybrid rye because it allows silage to be taken off much earlier because of the seeding time, and it would allow producers to capitalize on winter and spring moisture.

Barley, on the other hand, is more commonly used in silage, the cattle seem to prefer it over hybrid rye, and based on their research, cattle seem to gain more weight on it.

However, Penner says the research implies that one isn’t better than the other. Rather, that hybrid rye silage and barley silage could likely be most beneficial when used in tandem with one another.

“What our data consistently tells us is if we’re backgrounding cattle, we’re probably not going to get the same productivity out of those cattle if we feed all hybrid rye,” Penner says. “So in that case, we might want to feed low inclusion rates of hybrid rye and provide barley silage as the other component.

When you deal with finishing cattle, it looks like there is an opportunity for an all-hybrid rye silage component within their diets.”

Although ergot has always been a concern when feeding rye to cattle, with hybrid rye silage, Penner says there’s less risk.

“When we’re harvesting hybrid rye silage, part of the management is to cut that plant early and before major risk for ergot growth. It’s not that ergot couldn’t be developed, but it would be smaller ergot bodies within the kernel. So, we’re decreasing the concentration, and then on top of that, we have all the forage biomass. So again, it dilutes out the potential effects of ergot.”

Future research

Now, Penner and Zhang are getting ready to start the second phase of this research: looking at animal welfare measurements.

“I will start my year two confirmation study,” Zhang says. “We will have a similar experimental design as we had for the first year.”

Penner says the continuation of this study also goes hand-in-hand with some other research being done on hybrid rye.

“We’ve also completed all the work relating to hybrid rye grain use relative to barley grain use and we have two more detailed nutritional studies where we evaluated how the hybrid rye silage is digested in cattle relative to the barley silage,” Penner says.

Penner says in the future, hybrid rye silage might become an option for producers in harsher climates.

“Managing weather variability, I think, is of greater importance than it has been historically,” he says. “And there’s a number of different approaches you can use to manage that risk. But winter cereals might be an opportunity for producers that feel they’re in areas where they’re getting more fall precipitation as well as snow melt or spring precipitation, particularly if they’re in an area highly prone to adverse weather events during the summer.”