With the fall run starting, cattle feeders across the country are looking to fill empty pens. Typically, this involves purchasing yearlings off grass in September/October and then filling up with weaned calves later in the fall/early winter. Assembling and transporting these cattle to the feedlot, while critical from an economic perspective, is only the first step in the overall management program. Equally critical to the overall health and performance of the cattle is getting them started on feed in a timely fashion. With this column, I would like to look at some of the issues cattle feeders face when starting cattle on feed, particularly the challenges with starting newly weaned calves.

Before proceeding, let’s look more closely at these two groups of animals, particularly at characteristics that influence how they handle stress. First, let’s compare age. Yearlings coming off grass are 15 to 18 months of age while newly weaned calves will typically range from five to eight months of age. This difference has important implications for starting these two groups of cattle. A newly weaned calf is still missing its dam, its immune system is not as well-developed as that of a yearling and the act of weaning has forced the calf to transition from a milk/grass diet to one of forage/grain. In addition to weaning issues, newly weaned calves do not handle stressors such as transportation and mixing as well as yearlings. They also need more time to adapt to new surroundings. In particular, they need to learn to eat from a feed bunk and drink out of a water bowl.

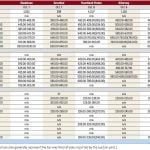

In short, newly weaned calves experience a great deal more stress than yearlings and as a result, take longer to get onto full feed. The challenge is best understood by considering the variation in feed intake that can occur during the first four to six weeks of a calf’s life in the feedlot. Let’s do this by looking at the dry matter (DM) intake record of a pen of calves averaging 500 pounds. It should not come as a surprise to anyone if this record indicates that during the first week or so on feed, the DM intake of these calves only averaged 1.0 to 1.25 per cent of body weight (i.e. five to six lbs. DM). This is barely enough feed to meet maintenance energy and protein requirements. It is certainly not sufficient to allow for weight gain or development of a fully functional immune system. Ideally, this animal should be eating at 2.5 to 2.7 per cent of body weight or 12.5 to 13.5 lbs. of DM. Closing this gap in as short a time as possible should be the main goal of your receiving program.

Read Also

Picking the most efficient cows to rebuild your cow herd

A new cow ranking system to help beef farmers and ranchers pick the most efficient cows as they rebuild their herds.

In reality, it takes a minimum of 21 days to get these calves on full feed. However, if things do not go according to plan, it can take significantly longer to reach this goal. For example, I have seen situations where calves that have been on feed for 40 to 50 days are only eating at 2.0 or 2.2 per cent of their body weight. Not only are they behind in terms of performance, but it is also likely that they have experienced a great deal more illness (and associated treatment costs) and have a higher death loss. The question then is what steps can you take to help these animals get onto feed in a more timely fashion?

If we go back to how these animals are assembled before arriving at the feedlot, one major step forward for the industry as well as for individual feedlots would be to see an increase in the number of preconditioned calves purchased. Preconditioning refers to a weaning strategy that ensures calves are a minimum of four months of age at weaning, are weaned at least 45 days before sale, are accustomed to eating out of a feed bunk and are vaccinated according to a veterinarian’s recommended protocol.

While not a new idea, preconditioning is getting a renewed look by both the cow-calf and feedlot sectors, as it is a proven method of reducing weaning stress. The fact that preconditioned calves are older, are on feed and are vaccinated before weaning places them in a better position, particularly from an immunological perspective, to fight off the various disease challenges that await them in the feedlot. As such, preconditioning may be a method that helps the feedlot sector wean itself off the practice of mass medicating calves on arrival with antibiotics — a practice that essentially is designed to have the same outcome as preconditioning, that being to assist the calf’s immune system to fight off bacterial challenges while adapting to life in the feedlot. Unfortunately, accessing enough preconditioned calves and ensuring fair compensation for preconditioning efforts continue to be issues facing the industry as a whole.

The design of the receiving program — including processing protocols, pen design, pen conditions (i.e. mud, bedding, etc.), calf density as well as design of the receiving and subsequent step-up rations — can all influence the calf’s ability to handle stress and as a result, its desire to eat. Next month we will look at some of these factors as we continue to explore this important topic.