Pen riders are quintessential cowboys of the modern era — riding through groups of cattle, cowboy hats or baseball caps pulled low to block the sun as they note every single animal in the feedlot. Even in the winter, with frost building on the faces of cattle, horses and humans, pen riders are riding the feedlot, because there’s always work to be done.

One of the most important jobs of a pen rider is identifying sick cattle in the feedlot and pulling any ill animals for treatment. At the top of their list is bovine respiratory disease (BRD), a common and costly disease. BRD includes any pathogen that affects the upper or lower respiratory tract. Bacterial infections, viral infections or stress can trigger the disease, but they usually all work together. It is most common in feedlot settings because of the stresses of transportation and the mixing of cattle from different operations.

Now, researchers from the University of Saskatchewan are trying to figure out how to fine-tune the accuracy of visual diagnosis for BRD.

Read Also

Unwinding the fibre in feedlot cattle diets

Research into how barley rolling method and undigestible NDF levels affect animal performance and digestive health in finishing diets

BRD struggles

When Katrina Garneau started doing more research into BRD, she discovered a new passion.

“This is something that people struggle with — everyone, even pen riders struggle with it,” Garneau says.

“I think at the end of the day, we all have to come together and figure it out together. But if I can help figure it out a little bit? Oh, my gosh, that would be so cool.”

Garneau is working on this research as part of her master’s degree, supervised by Dr. Diego Moya, an assistant professor at the University of Saskatchewan’s Western College of Veterinary Medicine.

Moya says the main concern they are trying to address with this research is to standardize the identification of ill cattle in feedlots, as symptoms vary between animals. He says the accuracy of pen riders is around 65 per cent. When animals with BRD aren’t caught, they can spread the disease to other cattle.

“We want to optimize the way pen riders identify those clinical signs, ideally at an early stage,” Moya says.

Conducting research

Garneau went to feedlots in southern Alberta, northern Saskatchewan and parts of Ontario, where she connected with pen riders at each feedlot.

Garneau says she followed the pen riders and spoke with them to find out why they pulled a cow. GoPro cameras on the pen riders’ heads allowed her to see what the pen riders saw when pulling cattle.

“They basically told me exactly when they’re going to pull an animal and the tag number,” Garneau says.

Garneau says she had a clinical scoring sheet where they would write down all the clinical signs of BRD in cattle, such as lack of eating, laying down and moving away from the bunk.

When the pen riders brought the cattle to the chute, Garneau and the other researchers looked for the symptoms the pen riders noted when they pulled them.

Garneau says they took body temperature, as well as looked at blood lactates using a lactate monitor. They also used the new “Whisper on Arrival” technology by Merck Animal Health. The tool looks like a paddle with stethoscopes on it, and measures an animal’s lung and heart noises. It includes a predictive algorithm indicating whether the animal needs to be treated for BRD.

Results so far

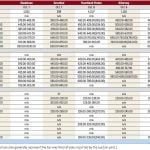

Garneau says they have three case definitions for BRD severity from this study. The first is rectal temperature of 104 F or above. The second is adding lactate readings to rectal temperature, and the third is adding the lung reading with rectal temperature.

She also says most of the animals being treated for BRD had nose secretions.

“So whenever you add another parameter, it narrows down the amount of cases. It’s interesting because we saw a significant difference in the frequency of nose secretions between all three case definitions.”

She says with chronic cases, which is an animal that has been treated four or more times, abnormal respiration is higher. Antimicrobial resistance is likely the culprit in such cases.

Garneau says there weren’t enough BRD cases over the two years they conducted this research to create a standardized protocol based on their results. However, she plans to continue the research to validate results.

With the work they’ve done collecting data on pen riders and how to improve their accuracy, Garneau says she hasn’t cracked the code yet on which cattle should be pulled and which shouldn’t be. But she’ll keep working with the data and videos from the pen riders.

Moya says they’re compiling the data for pen riders.

“So far, it seems like there’s quite a lot of variability in those riders successfully identifying sick cattle versus those that maybe were focusing on other things. So there’s no one single thing that we can point out as determining how good the pen rider is,” Moya says.

Moya says the final reporting date for this research is in 2024, but he says they want to go back out to the field to acquire more data.

“And at the end, what we want is to have information that can actually be used by the industry. So for that, I think we believe that more data is needed before we can go to the industry and provide some advice to them on how to improve their diagnosis. And that’s what we’re working on right now.”