Located 28 km north of Hanna, Alta., Scapa’s claim to fame is one of tragedy.

On January 29, 1907, a fierce blizzard struck. When it ended a few days later, two men were dead, about 550 head of beef cattle and horses perished, and only one man survived — and just barely. Montana rancher Lee Brainard perhaps took too many risks in an unknown country during a harsh winter. The result was almost inevitable.

“He was a little reckless, but he had a lot of determination,” says Scapa farmer Leo Erion, who lives near the site of the tragedy.

Read Also

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

In 2007, a retired RCMP officer from Stettler came out and visited a few local ranchers. The officer’s purpose was to ascertain where the blizzard had struck, where the men and beasts died, and where Brainard began his walk for survival. The officer met with rancher Gus Mattheis, now deceased (also tragically, in a farm tractor rollover accident in September 2015). Mattheis instigated the idea of a memorial site almost exactly where the tragedy had unfolded 100 years earlier.

“It’s within a half mile of the memorial site,” Erion says. The site is about two km south of Scapa on Range Rd 150, which connects Scapa to Hanna, on road allowance land.

Erion remembers Mattheis organizing meetings of area farmers and ranchers. “A few of us in the community got behind it,” Erion says.

The plaque was cast in nearby Alliance. It cost only $120. “We all chipped in,” he says.

Erion adds that they got the wording from the Glenbow Museum archives.

The huge rock was chosen “because it resembles a saddle or a sway-backed horse,” Erion says. The old maple log at the top is from the area — any around were grown for shelterbelts, he adds.

The actual tragic tale, headlined “Death Rode the Blast,” is recounted in details in the August 1951 edition of Canadian Cattlemen. And a decade or so ago, area rancher Helen Brunner Standing retold the story in a three-page poem entitled “Death in the Blizzard’s Wake.” She grew up on a ranch three miles south of the tragedy site.

Both accounts tell of Brainard seeking more open space from his Bozeman, Montana confines. His first wife had died and so he took his teenage son Albert, elderly hired man Hampson White and livestock, and in midsummer of 1906 he struck out for this dreamy “chinook belt” nirvana in east-central Alberta.

At Medicine Hat, the RCMP had warned Brainard of the perils of the raw frontier in winter. He ignored them. He settled briefly in fall about three miles north of present-day Richdale, Alta., along Berry Creek.

However, one October morning Brainard awoke to snow on the ground. And to his dismay, it never melted. No chinook arrived. In fact, more snow piled up. Their only shelter was a covered wagon. The cattle and horses had to rustle their own food. The temperatures soon hovered at 30 to 40 F below zero. Cattle began to die.

On January 29, 1907, a warm chinook finally blew in and caressed the cowboys. They worked in shirtsleeves. Brainard decided to move northwards, maybe 12 miles, likely towards the southwestern edge of Sullivan Lake. He used the horses to break the trail. They were headed to Hunts’ ranch and feedlot, about five miles southeast of present-day Endiang. Brainard had met the Hunt brothers a few months back and they had urged him to bring his stock there for the winter. He had refused until now.

In late afternoon, the wind died down and a mild calm settled in. The group ate supper. Young Albert suddenly jumped up and yelled “For God’s sake! Look what’s coming!” the 1951 Cattlemen account states. A grey wall descended upon them from the northwest.

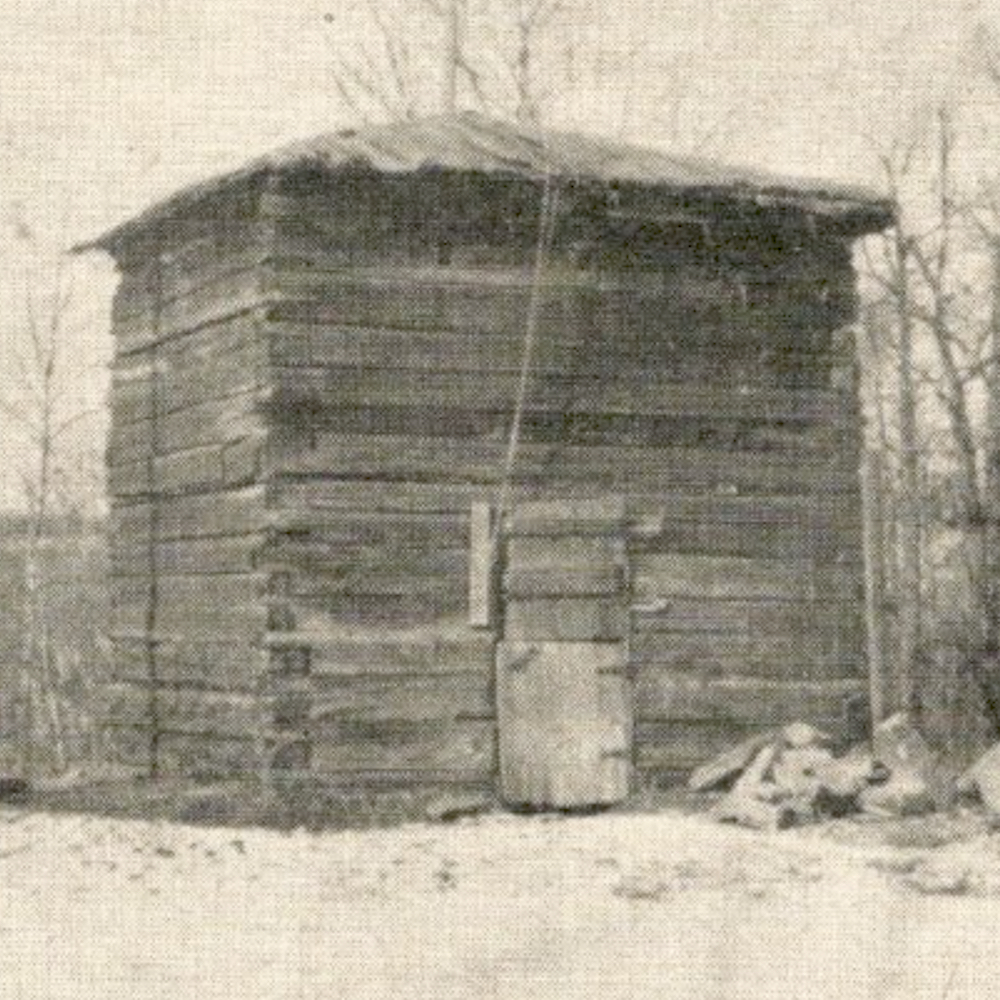

In the space of maybe two days, White and the boy were dead, along with most of the livestock. Brainard had better winter clothes and he stumbled off towards the Hunt place, sometimes crawling on all fours. He followed a fenceline and incredibly found the Hunt shack and collapsed against the door. He had survived.

Erion says it puzzles him to this day how Brainard found the Hunt ranch. “It must have been an eight-mile walk in the blizzard.” His other question is “Where are the two bodies buried?”

Brainard went on to lose nine toes. However, he recovered and rebounded. He and his second wife had two daughters. He ranched in the Fort St. John, B.C. area until his death in 1938 at age 79.

In 2019, Brainard’s grandson, Merle Keddie, came out from Hythe, Alta., on a goose-hunting trip. He met with several ranchers and sought answers to a few questions. He met with Maureen (nee Hunt) Wasdal of Endiang. Her grandfather, Harold, was one of the three Hunt brothers who had been in the farm shack when Brainard knocked on the door that cold evening in 1907.

Wasdal notes that her family still has a saddle from the Brainard horses. She is unsure if it is Lee Brainard’s actual saddle.

Wasdal and Erion both say that locals and Keddie had planned a get-together for this past summer at the Scapa Hall to revisit the tragedy and perhaps fill in a few gaps of information. The COVID-19 pandemic put a halt to that idea.

“Perhaps next year,” Wasdal says.

The inscription on the Scapa Memorial

End of a Dream: The Brainard Tragedy Site

In the winter of 1907 Lee Brainard and his son, Albert Day Brainard, and his hired man, Hampson White, were moving 450 head of cattle and 100 horses to the Hunt Ranch when they were caught in a winter blizzard. Albert and Hampson and most of the cattle and some of the horses perished in the storm at this approximate site.

Mark Kihn grew up on a mixed farm at Basswood, Man. He writes out of Calgary, Alta.