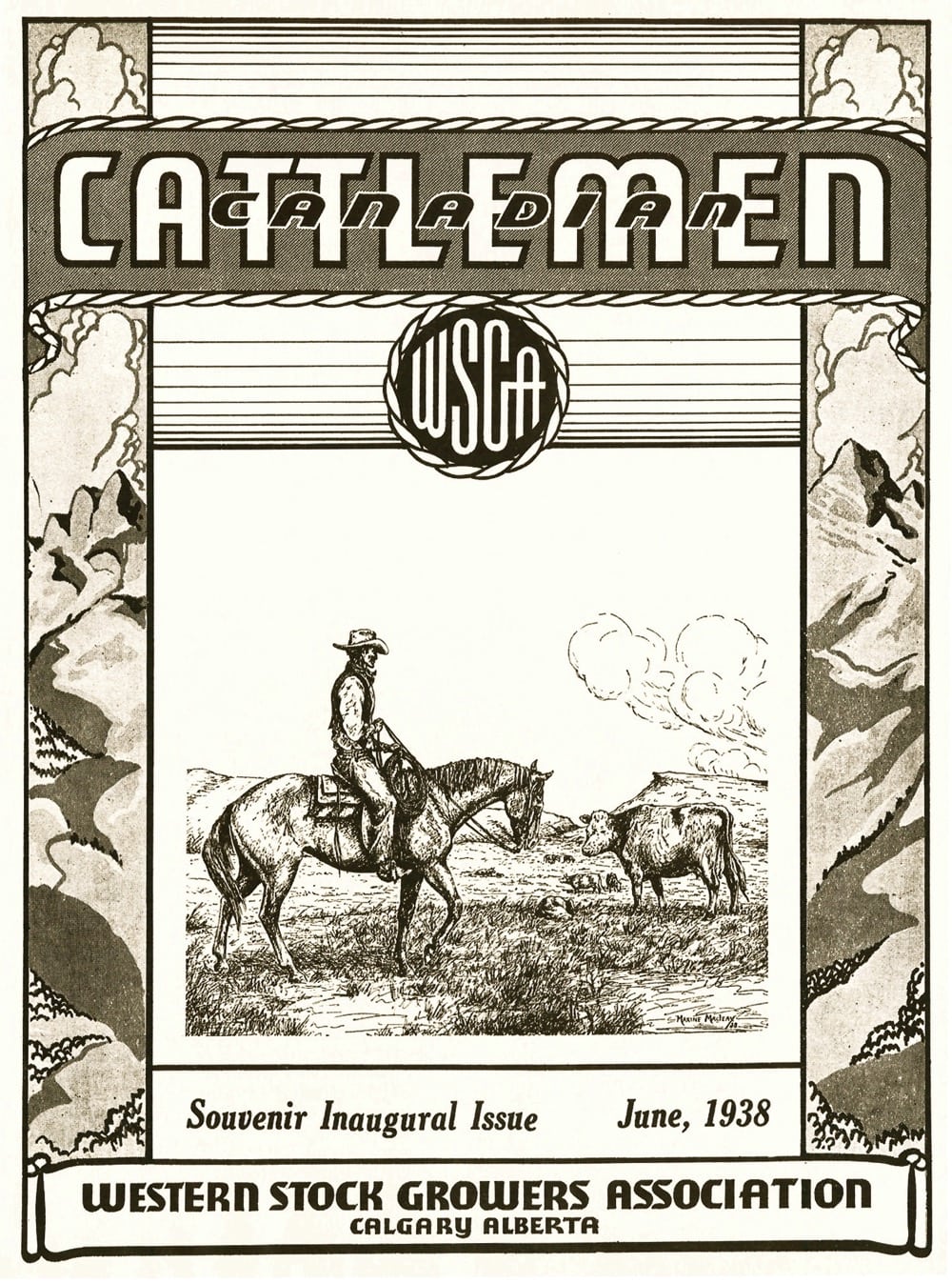

Our June 2018 issue marks the 80th anniversary of Canadian Cattlemen, which first appeared as a “souvenir” issue published by the Western Stock Growers Association (WSGA) in June 1938.

To honour the occasion I decided to take another look back through that first issue to gain some perspective on how things have changed in the past eight decades. For this I am most grateful to librarian Jana Wilson at the Bert Sheppard Memorial Library and Archives in the Stockman’s Memorial Foundation in Cochrane, Alta. To my knowledge it maintains the only indexed collection of our magazine right back to the first issue.

Read Also

Growing Canada’s beef herd: CCA’s priorities working with new federal government

This is my first column since the federal election. The Canadian Cattle Association works with all elected officials and parliamentarians, regardless…

As you might expect that first issue focused primarily on the early days of the Western Canadian cattle industry right up to their present day in 1938.

Senator D.E. Riley, then honourary president of the WSGA, looked back another 50 years to May 1883 when he walked into Alberta from Winnipeg behind a Red River cart and first saw the Rocky Mountains towering over the foothills.

“The country when I first saw it was virgin wilderness, void of all life but wild game, and knee deep in the rich Buffalo grass, a forerunner of the wheat fields to come. Only the whitened piles of bones, here and there, reminded one of the countless buffalo herds that had vanished but short years previously. The range that they had used remained and was not to lie idle for long.”

By the early 1880s the cattle industry was flourishing in the Western States and the ranges were badly overstocked. Encouraged by glowing reports of endless grass from whiskey traders and adventurers who had penetrated what is now Alberta, cattlemen soon started moving up to 10,000 head north. The first large herd owned by Senator Cochrane of Quebec arrived in the fall of 1882, followed quickly by the North West Cattle Company owned by the Allans of Allans Steamships of Montreal that started the Bar U herd.

The “76” herd brought in by the Powder River Cattle Company arrived as a dry herd. The calves were killed as soon as they were born with the result that their herd withstood the winter with fewer losses than other herds.

There were no settlements, no wire fences, no taxes and no restrictions, truly the “good old days” for the free range cowboy riding in large communal roundups, each outfit’s riders matching calves to its cow’s brand and marking them in turn.

By 1882 these early ranchers sought out some security to this new range and were granted leases up to 100,000 acres at one cent per acre per year from the Dominion Government on the stipulation that they must have one head of stock for each 10-acre parcel within three years. By 1884 just 41 companies and individuals held 1,782,690 acres under lease from the government, plus 900,000 acres upon which no stock had been placed.

It all worked quite well until the hard winter of ’86 and ’87 when three-quarters of the cattle perished in the bitter snow. Many of the large leases were cancelled due to non-payment of fees but those outfits that survived were careful to wean the calves in the fall and put up all available feed to carry the cattle through the next winter.

The advent of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885 was another marker for change and by the early 1990s the steel highway was bringing in a wave of competition for the cattle industry in the form of farmers, barbed wire and wheat.

Even some 30 years later Frank Ward, president of the British Columbia Beef Growers, couldn’t mask the frustration he felt at that change. “Looking back a few years to 1904 the farmer aided by politicians brought catastrophe to the Prairie beef herds,” he stated in our first issue. “Since then farming taxes and grazing fees were imposed forcing herds of magnificent beef cattle out of existence and alas, substituting a non-descript cow to milk.”

“No protection was given the industry by the governments of that day. If an acre of Crown land in southern Alberta could be ploughed it was marked “arable — not to be leased.”

Ward clearly blamed these policies for degrading the quality of cattle in Western Canada, a view he carried with him when he was “forced” out of southern Alberta to British Columbia where he became an early champion of a national grading system to rid the country of what he considered to be low-grade cattle.

Cattle baron Pat Burns was another who was concerned with the number of inconsistent “scrub” cattle in the west at this time. Unlike Ward, however, he advocated for smaller diversified farms with smaller herds of higher quality. In his own operations he bought high-grade Hereford bulls to upgrade his own production.

Then came 1931 and the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of $3 per cwt on cattle weighing over 700 pounds that basically closed the U.S. border. “Fine range steers sold as low as $2 per cwt with producers begging buyers to make a bid,” recalled WSGA manager Jack Byers of that time.

In 1933 and 1934 a large percentage of western cattle that were marketed went overseas, mostly to England, although the numbers were nothing like they were during the 20 years before. Exports of live cattle to the U.S. ranged from roughly 453,000 in 1919 to 866,000 in 1925. In 1930 they fell to 19,000 and change, 9,000 in ’32 and less than 6,000 in ’33.

At the same time England took 27,000 in ’31 and nearly 54,000 in ’34, still well down from what they were buying in the 1920s, though. Even that market was threatened in September 1933 when England abandoned the gold standard until the federal government stepped in and stabilized the dollar at $4.60 per pound.

Those were bad times but as Pat Burns advised a Calgary audience during the depression, “hang onto the cow’s tale and she’ll pull you through.”

Of course these pioneers were unaware that foot and mouth was lurking in the future, then tuberculosis, and the long weary years of test and slaughter to gain TB-free status and, of course, BSE. But that was the stuff of later issues in the magazine that began in this month in 1938.

It has been a wild ride so far, but if you can be sure of one thing, it is that there is much more to come.