The term “biosecurity” is used throughout all aspects of food production, from growing food to moving commodities between different sectors, placement on grocery shelves and finally consumption and waste management. They are all related and all have their biosecurity plans. Those plans seldom account for what comes before and what follows.

For the livestock industry, biosecurity is basically about plans to analyze and manage risk, primarily as it relates to disease. More specifically:

- Control over diseases that affect milk, meat or animal production.

- Diseases that make your farm or farm business less productive.

- Anything that seriously affects the quality of your produce or your reputation.

- Anything that causes health problems for you, your employees or customers.

Attention to biosecurity helps promote sustainable agriculture, improve public health and protect the environment. There are a variety of approaches to biosecurity, driven mostly by the type of enterprise under consideration. An equine stable is very different from a commercial broiler operation. Egg layers have different biosecurity needs than an intensive hog production facility. Cattle feedlot biosecurity plans vary significantly from biosecurity protocols designed for dairy barns.

- RELATED: Keeping foot-and-mouth disease out

- RELATED: One Health strategies help farm family navigate outbreak

- RELATED: Beware zoonotic diseases in your herd, says university veterinarian

One area I consider particularly difficult to consider is sound biosecurity practices for large grazing leases which may cover 15,000 to 20,000 acres of Crown forestry lands within the Alberta foothills or thousands of acres of natural prairie that run off the east slopes into inhospitable areas of the Palliser Triangle. For these operations, there is no easy way out for sound “on-ranch” biosecurity. The reasons being:

- Miles of fenceline contact with neighbouring producers.

- Patrons often involve shared range with other cattle owners.

- The presence of different cattle types on one range: yearlings, breeding-age heifers, bulls, mature cows with calves at side, and some cows calving on range.

- Shared watering sites.

- Uncontrolled contact with wildlife capable of carrying and transmitting disease.

- Poor fenceline security e.g., old fences, downed fences.

Cattle are often trucked to pasture destinations with little attention paid to exposure during transport (dirty trucks moving between premises, providing exposure to what exists in other herds).

For me, biosecurity plans for many livestock sectors become similar when laid side by side. Other than disease control — because many diseases are species-specific — yard and premise security are carbon copies, and disease prevention and control principles vary only by etiology and age.

Read Also

The Canadian Cattle Association’s international advocacy efforts

Global ag policies affect Canadian food policy, so the Canadian Cattle Association participates in international and domestic forums

Dr. Nick Lyons of Pasture.IO (Australia), a veterinarian specializing in international animal health, maintains that “biosecurity is a verb,” which means it’s always being applied to changing situations. His feelings on biosecurity mirror those of Dr. Franklyn Garry, professor at Colorado State and speaker at the University of Calgary Veterinary Medicine’s Beef Cattle Symposium, that “biosecurity” can be broken down into strict biosecurity practices aimed at preventing a disease from entering an operation — such as foot-and-mouth disease — to biocontainment or hygiene management aimed at preventing the spread of disease ubiquitous within many operations such as calf scours and respiratory disease.

In Franklin’s view, the easiest path for most producers is to look for a “solution in the bottle.”

Records are an important part of whatever system melds best with either approach. The producer workbook, prepared by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency with substantial input and review by the Beef Cattle Research Council, is worth a read. It’s meant to help producers prepare for an emergency and to help improve their ability to react quickly to the unexpected. Keeping the plan current and sharing it regularly with everyone on the operation will make it more effective. It’s suggested that livestock producers review their documents annually — for example, when insurance policies are reviewed each year.

Make sure that everyone has access to and understands the information. The workbook’s authors suggest incorporating an emergency management overview into new staff orientation and other training opportunities.

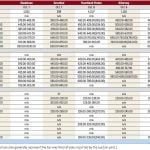

Each operation has unique features, so the workbook tools are meant to be adaptable and easy to understand. The table of contents provides a quick overview of what should be considered by producers when formulating a biosecurity or health management plan, such as contact lists, visitor logs, visitor risk assessments, as well as protocols for unusual animal health events, notice of suspicion response, mass vaccinations, etc.

For more information about animal health emergencies or to download the producer handbook and other useful resources, please visit animalhealth.ca.