If starch (from grain) is the fuel in a feedlot diet, fibre (from a roughage such as silage) is the engine governor that slows digestion. A backgrounding diet might contain 60 per cent silage to moderate animal growth so that they grow frame and muscle without over-fattening. In finishing diets, grain levels are increased to optimize weight gains and feed conversion, while silage is reduced to 10 per cent or less of dietary dry matter content to provide just enough “scratch factor” to maintain rumen function and pH, and reduce the risks of feedlot bloat, founder, liver abscesses and other problems that can compromise health, gains and efficiency.

Silage is sometimes viewed as “just” a fibre source, so the choice of silage crop is often based primarily on potential crop yield and agronomic considerations. High-yielding hybrid corn silage predominates in regions where there are enough heat units and water to support it. Western Canada has traditionally relied on barley silage due to its relatively high yields, early maturity and reasonable drought tolerance. In recent years, wheat has become a more popular silage choice because of its increasing yields, lodging resistance and wider harvest window. Potential nutritional or feeding differences between barley and wheat silage haven’t been studied in detail.

But silage is more than “just” fibre. Not all fibre is created equal. As an extreme example, dried distillers grains may contain 25 to 50 per cent fibre, but their fibre fragments are too short to provide the scratch factor that stimulates rumen contractions. They’re also so short that rumen bacteria digest them rapidly — fibre from distillers grains is essentially another energy source. Fibre that is long enough to provide the necessary scratch factor is called “physically effective.” Silage chop length affects how physically effective the fibre will be. Short-chopped silage packs and ferments better, but long chop lengths are more physically effective in the rumen. Chop length is a balance between silage quality and animal health considerations.

Read Also

Unwinding the fibre in feedlot cattle diets

Research into how barley rolling method and undigestible NDF levels affect animal performance and digestive health in finishing diets

Greg Penner (University of Saskatchewan) and collaborators studied the Effect of Silage Source, Physically Effective Neutral Fibre, and Undigested Neutral Detergent Fibre Concentrations on Performance and Carcass Characteristics of Finishing Steers.

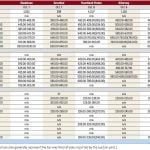

What they did: Four finishing diets were fed once daily in a small pen study (360 crossbred yearling steers, 15 head per pen, six pens per diet). Each diet contained 90 per cent concentrate (primarily barley, dry-rolled to a 66 per cent processing index). The 10 per cent roughage portion used different silage crops (AC Ranger barley versus CDC Landmark wheat) and chop lengths (half versus three-quarter inch) to produce different physically effective fibre levels, but all other nutrient levels were identical among the four diets. Steers were finished for 100 days, then slaughtered and carcass data was collected.

What they learned: Silage crop, chop length and their combination did not have any meaningful impacts on feed intake, growth rate or feed:gain. Some interesting differences showed up in the carcass traits, though.

Silage source mattered. Barley silage produced significantly heavier carcass weights (827 lbs. versus 818 lbs.) but slightly more livers with minor abscesses (17 versus 12 per cent) than wheat silage.

Physically effective fibre mattered. Long chop lengths (higher physically effective fibre) produced significantly higher dressing percentages (59.4 versus 59 per cent), more AAA grades (78 vs. 68 per cent) and fewer AA grades (22 versus 32 per cent) than short chop lengths (lower physically effective fibre), regardless of whether it was barley or wheat silage.

Physically effective fibre was particularly important with wheat silage. Long-chop-length (both wheat or barley silage) and short-chop-length barley silage produced significantly fatter carcasses (55 versus 63 per cent yield Grade 2 and 33 versus 22 per cent yield Grade 3) and fewer severe liver abscesses (21 versus 29 per cent) than short-chop-length wheat silage.

So what does this mean: Silage is more than an inconvenient dietary necessity in finishing rations. Silage is a small proportion of the finishing diet, but subtle differences may have real impacts. In this case, the higher physically effective fibre level didn’t impair animal performance, but it did improve carcass grades for both barley and wheat silage.

AC Ranger barley silage outperformed CDC Landmark wheat silage in this study, but that doesn’t mean that any barley silage is better than all wheat silage. There’s probably as much variation between varieties of the same crop as between different crops. The economic advantage of wheat silage, particularly concerning lodging and its wider harvest window, may also outweigh the feeding benefits of barley silage in some situations.

Good timing, good weather, good luck and good technique likely have more effect on silage quality than the crop or chop length used. But if conditions allow cereal silage to be harvested at the optimal 30-40 per cent dry matter, consider using a longer chop length due to the grading benefits. In contrast, if silage is too dry at harvest time, longer chop lengths will make it harder to pack and will reduce silage quality. If silage is harvested late, it’s better to chop it more finely. More mature crops will have higher fibre levels and that will also make for more physically effective fibre.

The Beef Cattle Research Council is funded by the Canadian Beef Cattle Check-Off. The BCRC partners with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, provincial beef industry groups and governments to advance research and technology transfer supporting the Canadian beef industry’s vision to be recognized as a preferred supplier of healthy, high-quality beef, cattle and genetics.