[UPDATED: Dec. 17, 2018] Thanks to 3D modelling, scientists have a better idea of how a liver fluke infests livestock.

Dicrocoelium dendriticum, commonly known as a lancet fluke or lesser liver fluke, can cause liver disease in cattle, sheep and goats. The Merck Veterinary Manual notes that livestock don’t seem to have any immunity to the flukes. Animals can develop heavy infections with minimal clinical signs, but they can develop health issues such as liver cirrhosis.

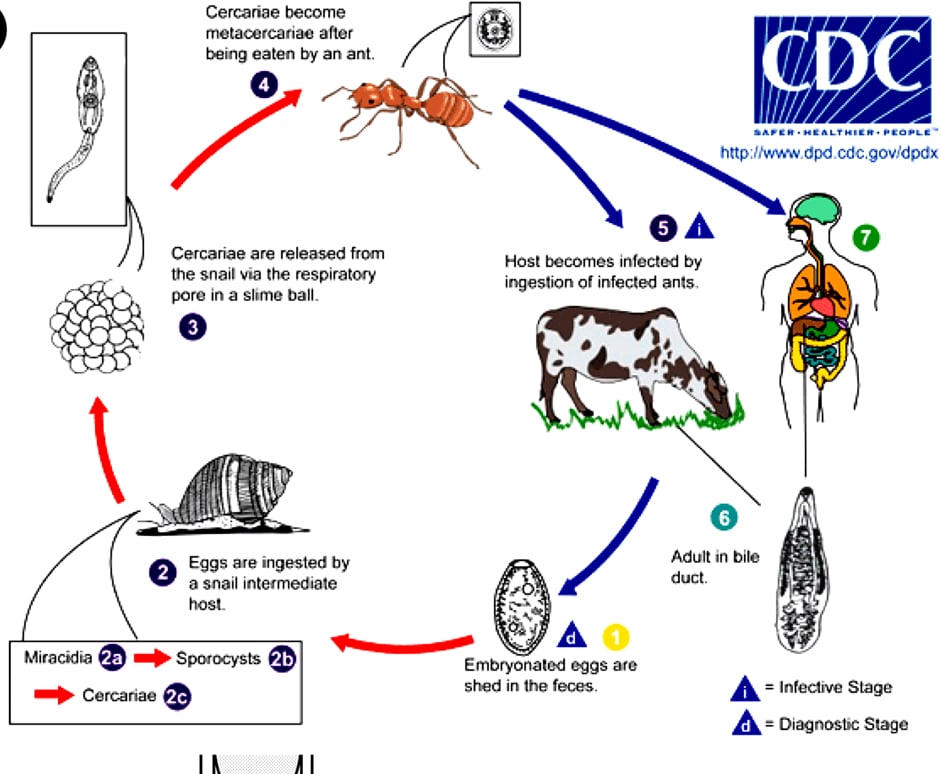

The lancet fluke’s life cycle includes several phases. Snails initially host the flukes. Fluke larvae emerge from the snail and sit in a slime ball, which the ant ingests. Most of the flukes remain in the ant’s stomach, but one or two move to the brain.

Read Also

Body condition, nutrition and vaccination for brood cows

One of the remarkable events of the past century related to ranching has been the genetic evolution of brood cows….

Somehow the parasites compel the ant to cling to the tip of a plant where it’s more likely to be ingested by grazing animals. The flukes begin laying eggs 10 to 12 weeks after the unsuspecting grazer has swallowed the ant.

Scientists were puzzled by how the parasites control the ant. Researchers used micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scanning to create virtual 3D models of the infested ants. Using those models, they could pinpoint the parasite’s location in the ant’s brain. They also saw that the fluke grabs some of the nerves that control the ant’s jaw muscles.

“This was a good example of how science should work — discussing ideas with colleagues, following our instincts wherever they take us, and in this instance, making a discovery,” said Dr. Douglas Colwell, a researcher with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), in an AAFC press release. Colwell worked with colleagues at the University of Lethbridge and London’s Natural History Museum on the project.

The hope is this new knowledge will help researchers figure out how to change the parasite’s behaviour. Researchers will also be able to use the scanning technology to study other parasites that affect livestock and insects.

*A previous image included in this article showed an incorrect life cycle of the liver fluke mentioned above. We apologize for any confusion this may have caused.