Food safety problems related to Canadian beef rarely make the news these days, because they hardly ever happen. That hasn’t always been the case. Canada’s food safety has come a long way over the past century. Researchers Xianqin Yang (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lacombe) and Kim Stanford (University of Lethbridge) recently reviewed this history (A 99-year journey on the evolution of food safety in Canadian livestock production; doi.org/10.1139/cjas-2024-0150).

Where we started: In the 1920s, nearly 15 per cent of Canadian children died before two years of age because of a variety of milk-borne diseases including bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis. Pasteurization effectively dealt with these problems.

Bovine tuberculosis can also be transmitted through undercooked beef, but it’s virtually impossible to effectively pasteurize different beef cuts that vary greatly in size and thickness. Instead, potentially infected beef was detected based on the identification of tuberculous lesions in the head, chest and internal organs of cattle. Aside from that, meat safety was largely based on, “If it looks, smells or tastes bad, you probably shouldn’t eat it.”

Read Also

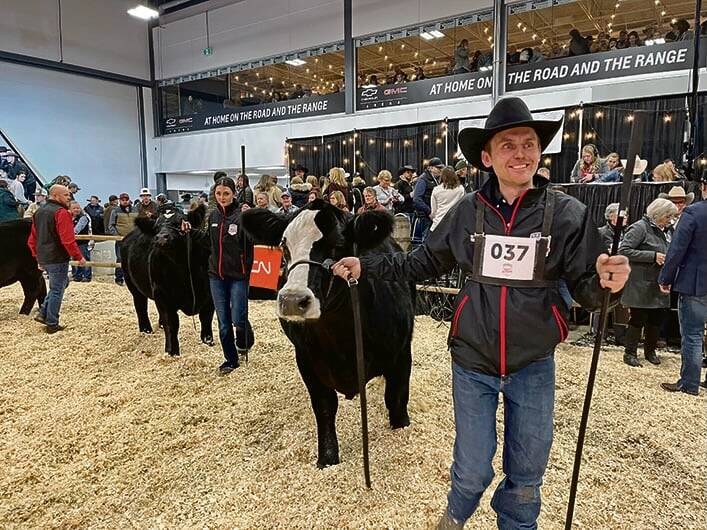

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

Canada began tracking foodborne disease in the 1970s, but limitations in diagnostic capabilities meant that the microbe responsible was only identified about 20 per cent of the time. This spurred the development of Canada’s foodborne disease reporting system. Being able to quickly and accurately identify pathogens in sick patients has greatly increased our ability to promptly track cases of foodborne illness to the initial source. But responding to problems isn’t nearly as good as preventing them from happening in the first place.

- MORE ‘Research On the Record’: Icebergs and native forages. What you can’t see can sink you

The Space Race: It’s important to make sure that astronauts don’t get food poisoning when two or three of them are crammed into a space capsule for weeks with diapers and no doctor. Initially, NASA set strict limits for microbial numbers and rigorous testing requirements that had to be achieved before food would be approved for the space program. Hardly any food passed these standards. After throwing a lot of food away, NASA decided that ensuring food was safe after it had already been produced wasn’t going to work. The food production process itself needed to be improved.

They found the solution in the rocket-building manual. Early rockets could not be fixed in mid-flight, so everything had to be assembled perfectly and function properly every single time. That meant paying extremely close attention to every detail of the rocket manufacturing process. NASA worked with the Pillsbury company to adapt that prevention-based approach to space food production. They identified every point in the production process where food could potentially be contaminated, developed effective ways to prevent or control those potential contamination points, monitored them continuously, and kept meticulous records. This process worked. No NASA astronaut has ever gotten food poisoning in space.

What’s changed: The leading food safety concern in Canadian beef is Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) such as E. coli O157:H7. These bacteria were first detected in Canada in the early 1980s, and cases of STEC-associated human illness generally doubled every year throughout that decade. STEC don’t cause disease in animals, so there are no lesions to look for at slaughter. Bacteria are invisible to the naked eye, and it only takes 10 STEC cells to cause an infection. Random testing is an ineffective way to find an invisible needle in a haystack.

So, when the first big STEC outbreak killed four children and infected 732 other U.S. consumers in 1993, North American regulators and the food industry responded by adopting and implementing NASA’s approach to food safety. The critical control points they identified and solutions they developed to address potential food safety hazards have essentially eliminated STEC from beef carcasses (i.e., hide-on carcass washes, skinning and evisceration procedures, carcass and trim sprays, temperature control, sanitation of conveyors, cutting equipment, gloves, etc.). In the late 1990s, E. coli O157:H7 infections affected eight in 100,000 Canadians. That number dropped to four in 100,000 by the early 2000s and to one in 100,000 by 2010. NASA developed the principles, but the specific solutions that have proven effective for beef processing plants were developed by food safety researchers.

Where we are now: Prevention-based food safety systems are very effective when they’re implemented and operating properly, but pathogens still sneak through from time to time (which is why ground beef needs to be cooked to 71 C). Researchers suspect that bacteria are hiding in hard-to-clean areas, establishing colonies called biofilms that resist pressure washers, and periodically release pathogens that may contaminate beef as it moves through the plant.

So what does all this mean to you? Food safety underpins consumer confidence and demand for Canadian beef. Canada’s researchers develop effective solutions that help to prevent food safety problems from arising, and the check-off you pay helps fund their work.

The bottom line is the more we learn, the more we know, and the better we can do. Yesterday’s research underpins today’s safe beef. Today’s research will help avoid problems tomorrow. Canadian researchers are currently studying biofilms, and what they’re learning goes beyond food safety. It also has implications for on-farm biosecurity and animal health. Stay tuned for more.

The Beef Cattle Research Council is a not-for-profit industry organization funded by the Canadian Beef Cattle Check-Off. The BCRC partners with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, provincial beef industry groups and governments to advance research and technology transfer supporting the Canadian beef industry’s vision to be recognized as a preferred supplier of healthy, high-quality beef, cattle and genetics. Learn more about the BCRC at beefresearch.ca.