When consumers recognize your brand, it’s a sure sign that you’re doing something right.

At restaurants across southern Ontario, to see the name of one particular beef operation on the menu is a testament to the hard work of Kara and Darold Enright.

“Something that we are always trying to promote to the consumers is that we’re a local, trusted brand, and so when they see Enright Cattle Company listed on the menu, we’re hoping that they choose that item,” said Kara, who farms with her husband and two young children at Tweed, Ont. “We put a lot of effort into putting our brand in front of the consumer and having them associate it with a local family farm, an Ontario brand and something that they can trust and resonate with.”

Read Also

What to know before you go to Agribition 2025

If you’re attending Agribition 2025, this is the place to find out about tickets, dates and what’s happening this year.

This brand recognition didn’t happen overnight. It’s the result of years of work after the Enrights decided that direct marketing was the major change their business needed.

“We were working a lot of long hours trying to build the farm, and the farm was not even breaking even, let alone making a profit,” said Kara, who worked in sales for a feed company while her husband worked as a custom home builder.

“By 2009, when we decided to start our family, we felt that we just didn’t have enough time to continue in the way we were going, and we needed to make some drastic changes so that our farm would become profitable and sustain at least one of us as a full-time employee.”

Initially, their business plan included selling beef at farmers markets in Toronto and Kingston, which allowed them to learn more about promotion and consumer demands. “It was a huge learning curve from just watching the animal leave in a trailer to actually selling each individual piece,” she said. While this gave their business exposure, the volume sold wasn’t enough to allow them to reach their goals.

A turning point came when they sold steaks to a chef at an upscale restaurant in Kingston, and he returned the next week to purchase more beef. As more restaurants became interested in their beef, the Enrights changed their business plan to target the wholesale market. Today, Enright Cattle Company direct markets about 300 head per year, with their beef highly sought after by restaurants and consumers alike.

Their direct marketing plan relies on a value chain that includes themselves, Kara’s parents and a local abattoir. The Enrights raise the calves, grow the necessary feed crops and take care of marketing. To transition to this plan, Kara moved to a flexible part-time position for three years before being she was able to farm full time.

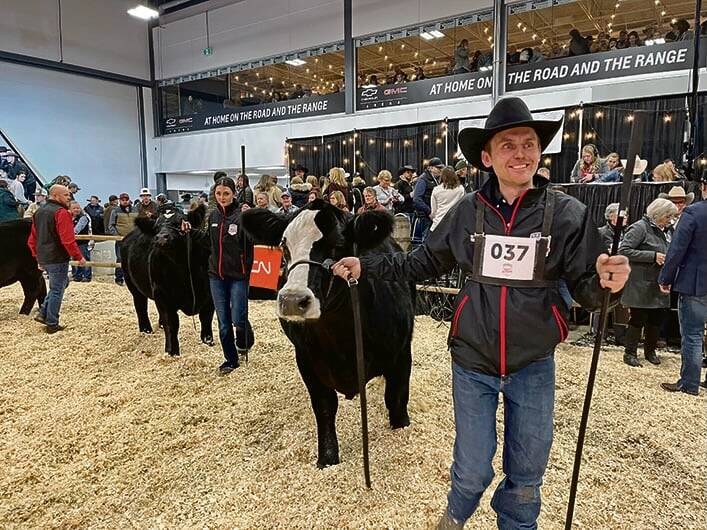

When the couple purchased their farm in 2004, they brought along Kara’s small herd that she had been building since her 4-H days. Their herd now consists of about 60 head of Simmental females, most of which are registered. First-calf heifers are bred to an Angus bull, and they AI mature cows to a Simmental bull before turning out their two Simmental herd sires. Most of their cows calve in February and early March, with some set to calve in September.

Kara’s parents, Don and Chris Langevin, farm nearby and finish all of the calves. “They also purchase other feeder calves and have them at the right weight slot so that we have cattle ready for harvest every week. So there’s approximately four different yards over at their farm that contain cattle in a pretty big weight range,” said Kara. The abattoir receives calves each week, dry ages the beef for 14 to 21 days and takes care of the packaging.

A key feature of the Enrights’ program is their traceability system, using the animal’s ear tag. “Any major events that happen within each animal’s life is electronically recorded, and that electronic file follows each animal throughout the different stages,” she said. Each package of beef has a label with a bar code tracing it back to the individual animal. They scan the bar codes to automatically create an invoice when filling an order, which lets them track where each package goes.

This also allows them to record the amount of saleable beef from each carcass, and is useful when they receive customer feedback. “If they’re extremely happy with a specific cut that they got, then we can trace it back to see which animal it came from and try to determine why (it was) exceptional and then obviously try to replicate it.”

About 95 per cent of their sales are to high-end restaurants in Toronto, Ottawa, Kingston and other communities in southern Ontario. They employ a driver who makes deliveries three days per week with their refrigerated van. The rest of their sales are direct to consumers who order online. They offer a variety of cuts, as well as special boxes ranging from $100-$300.

“We have always had a focus on trying to add as much value as possible so that we can be sustainable,” said Kara. “We’ve started tanning some of the hides and we work with a local leather maker who handcrafts them into bags, as well as leather aprons.” Their leather products are available to order online and are carried in stores in Ottawa and Kingston.

Building from the ground up

As the Enrights built their business, infrastructure and equipment were limited at times. “We had very minimal equipment, just what we needed to get by,” said Kara. “We were able to borrow equipment from my parents in exchange for labour.”

They rent pasture and rely on rotational grazing, regularly moving their cattle between paddocks that divide their pastures. When they purchased the farm, it had an existing barn with an open front and fence line feeder, and they’ve since added calving pens inside. They built a second barn nearby, with solar panels on the roof, a fence line feeder and space for their handling facilities.

“We have also utilized the East Beef Breeder Co-op to extend the cow herd. We’ve used the Eastern Ontario Feeder Co-op to purchase feeder calves,” she said. “We use FCC as our crop input for our loans to plant the crops, and we have a really good relationship with our bank to access loans for our different assets.” They have used grants to help build their business, including those offered by Growing Forward 2, the Community Futures Development Corporation and the Local Food Fund.

Meeting challenges

As with any operation that direct markets beef, consumers can pose certain challenges. One such consideration for the Enrights is selling cuts deemed less desirable. “We can only kill and cut and sell as many animals as our least desirable cuts are selling, so it’s always a challenge. It’s probably my biggest challenge every week, just to balance out that carcass and move the cuts that are less desirable, but they all go,” said Kara. In this case, their network of chefs and butchers is valuable when exploring how to add value to a cut and make it more attractive to consumers.

Current consumer perceptions can also be a challenge, and they receive many questions about their beef production methods. The Enrights don’t implant their calves, and they note that their beef has no antibiotic residue, as per the industry standard. “As far as antibiotics go, we tell all of our chefs that if the animals require treatment then we treat them for veterinary recommendation, but other than that we don’t,” said Kara. “They seem to be fine with that. They understand that it’s more common sense.”

In response to questions about grass-fed beef versus other types of feed, Kara explains exactly what they feed their cattle. “We walk them through the steps of how we come up with what we feed the cattle, and most consumers don’t realize that it’s that technical to feed cattle and that we actually have a nutritionist,” she said. “By the time that you explain that all out to them, that you really are getting the right amount of fibre and energy and vitamins and minerals, then they’re actually satisfied.”

There are other day-to-day challenges to consider, such as maintaining a healthy balance between work and life. Currently, Darold continues to work off the farm full time, and as the operation became more profitable, the couple was able to make some chores more efficient after a long work day.

For example, Darold often does chores in the dark when he gets home from work in winter, and their fence line feeder has made this simple. “Once I feed them, they all stand there in a perfect line, and it works great. I can sort out who I think is going to calve, throw them in and get a calving pen,” he said. “The next day, if Kara wants to check the cows when she has time, then it’s easier for her to just check the pens than it is to go out and check the whole herd.”

To nurture that work-life balance, the family makes sure they spend time together and makes family vacations a priority, often adding a few days to a conference or tour. “We always try to eat dinner together, so even if it means in the back of a pickup truck in the middle of a field, and it might just be sandwiches or whatever at that point,” said Kara.

The growth of their business will soon allow both Darold and Kara to work full time on the farm, a major goal of theirs. “To us, farming doesn’t feel like work,” she said. “We really enjoy it, we really love doing it, so it’s not such a bad thing to do the long hours when you really love it.”